The narrative on European integration is that it heralded in a new dawn of peace, democracy and human rights. The reality is that the EU’s foundations lie in the colonial histories of its founding Member States, an origin story with which it has never grappled. Brexit was also an emanation of nostalgia for empire, writes Nadine El-Enany (Birkbeck), in this edited extract from her new book Bordering Britain: Law, Race and Empire.

European integration, rather than marking a turning point or rupture in relation to a violent past, is instead on a continuum of European colonialism. Just as Britain passed immigration and nationality legislation designed to exclude racialised colony and Commonwealth citizens in the face of the defeat of its empire, European colonial powers came together in the post-war era to create a protectionist bloc to ensure that the spoils of European colonialism remained the domain of white Europeans. In view of this history, it is little surprise that Britain’s European partners have been accommodating of its imperial identity and has not posed a challenge to its exclusion of its former colonial subjects. In spite of this, a common misconception which gained traction in the run-up to the 2016 EU referendum was that Britain’s control over its borders is hampered by its EU membership. The reality is that Britain has always exploited its EU membership to enhance its capacity for control. It played the role of agenda setter in the context of early European intergovernmental cooperation on asylum and immigration policy, successfully pushing for the adoption of exclusionary policies across Europe. It retained its freedom to choose when to participate in measures on immigration and asylum after securing a flexible opt-out in 1997. Britain has consistently used its opt-out to participate in restrictive measures that strengthen its capacity to exclude, and out of those aimed at enhancing protection standards for people seeking refuge in the EU. Although it grudgingly accepted the principle of free movement of EU citizens, it did not join the Schengen Area and thus continues to exercise border controls in relation to the nationals of other EU Member States. In spite of this, the Leave campaign argued that exiting the EU would allow Britain to ‘take back control’ of its borders. Perhaps the most striking moment in this regard was when then UKIP leader Nigel Farage unveiled a poster depicting racialised refugees crossing the Croatia-Slovenia border in 2015 along with the slogan ‘Breaking Point’, despite the fact that these individuals would have had no legal right to enter Britain.

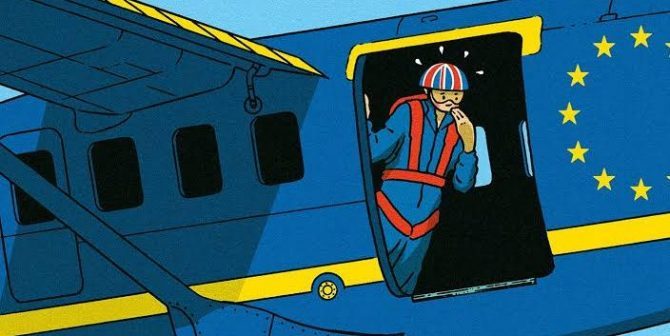

Brexit as nostalgia for empire

The 2016 referendum on Britain’s EU membership should be understood as another in a long line of assertions of white entitlement to the spoils of colonialism. The Leave vote should not be exceptionalised as an object of study, or collapsed into the meaningless hashtag that is ‘Brexit’, but instead understood in the context of Britain’s colonial history and ongoing colonial configuration. Exceptionalising the referendum result distracts from the structural forces underlying it. The terms on which the referendum debate took place are symptomatic of a Britain struggling to conceive of its place in the world post-Empire. Present in the discourse of some of those arguing for a Leave vote was a tendency to romanticise the days of the British Empire, despite widespread amnesia about the details of Britain’s imperial history. A 2016 poll conducted six months prior to the referendum found that 44 per cent of the British public were proud of Britain’s colonial history and 43 per cent considered the British Empire to have been a good thing. In 2011 David Cameron, then Conservative Prime Minister, stated that ‘Britannia didn’t rule the waves with armbands on’. Before him, former Labour Prime Minister, Tony Blair, stated in 1997 that he valued and honoured British history enormously and considered that the British Empire should neither elicit ‘apology nor hand-wringing’ and that it should be deployed to enhance Britain’s global influence.

The hankering after the halcyon days of empire was expressed in a tabloid headline following the referendum, which read, ‘Now Let’s Make Britain Great Again’. The slogan, popular in the course of Donald Trump’s presidential election campaign, has since been adopted by some of those who backed a Leave vote. The idea of ‘making Britain great again’ captures a yearning for a time when ‘Britannia ruled the waves’ and was defined by its racial and cultural superiority. The vote to leave the EU is not only an expression of nostalgia for empire, it is also the fruit of empire. The legacies of British colonialism have never been addressed, including that of racism. British colonial rule saw the exploitation of peoples, the theft of their land, their subjugation on the basis of a white supremacist racial hierarchy, a system that was maintained through the brutal and systematic violence of colonial authorities.

The British Empire was vehemently resisted by local populations in colonised territories. As Richard Gott writes, there was always ‘resistance to conquest, and rebellion against occupation, often followed by mutiny and revolt – by individuals, groups, armies and entire peoples. At one time or another, the British seizure of distant lands was hindered, halted and even derailed by the vehemence of local opposition’. Priyamvada Gopal has challenged the discourse prevalent in Britain that credits anti-imperial resistance to the liberal imperialist project. This project presents freedom from slavery and imperialism as having flowed from the ‘benevolence of the rulers’ and having been granted to colonies ‘when they were deemed ready for it’. Gopal’s counter history destroys this narrative, demonstrating instead how enslaved and colonised peoples were the agents of their own resistance and freedom. They also shaped British discourse on liberation, not only through scholarship but also in the form of struggle and insurgency thereby ‘interrogating the tenacious assumption that the most significant conceptions of ‘freedom’ are fundamentally ‘Western’ in provenance’.

Paul Gilroy has argued that imperial nostalgia is sometimes combined with ‘a reluctance to see contemporary British racism as a product of imperial and colonial power’. The prevalence of structural and institutional racism in Britain today made it fertile ground for the effectiveness of the Leave campaign’s rhetoric of ‘taking back control’ and reaching ‘breaking point’. The Leave victory on 23 June 2016 resulted in a renewed level of legitimisation of racism and white supremacy. In Britain, a week prior to the referendum, pro-immigration Labour MP, Jo Cox, was brutally murdered by a man who shouted ‘Britain first’ as he killed her, and who gave his name in court on being charged with her murder as ‘Death to traitors. Freedom for Britain’. In the months following the referendum, racist hate crime increased by 16% across Britain, and peaked at a 58% rise in the week following the vote. Weeks after the referendum, Arkadiusz Jóźwik was beaten to death in Essex, having reportedly been attacked for speaking Polish in the street.

In an article that has proved remarkably prophetic Vron Ware argued in 2008 that ‘societies where whiteness has historically conferred some sort of guarantee of belonging and entitlement present an opportunity for political mobilisation in the name of white supremacy’. The vote to exit the EU signified a shoring up of white entitlement to territory, resources, and to identification as British. Despite the frequent refrain that the 2016 vote to leave the European Union was the result of a disenfranchised ‘white working class’ revolt, Gurminder Bhambra has observed that the vote was disproportionately carried by ‘the propertied, pensioned, well-off, white middle class based in southern England’. According to Danny Dorling, 52% of Leave voters lived in southern England and 59% were middle class. The proportion of people who voted Leave in the lowest social classes was just 24%. The Leave campaign’s violent rhetoric of ‘taking back control’ is thus symptomatic of an imagined victimhood on the part of white nationalists, in part a backlash against the gradual gains made in the realm of civil rights and non-discrimination on the part of minorities living in white hegemonic societies over the past decades. James McDougall and Kim Wagner have pointed out that Enoch Powell’s ‘notorious line about the descendants of the enslaved and colonised gaining “the whip hand over the white man” was an early indication of the fantasy of victimhood that grip’s today’s alt-right and feeds hostility to migration and multiculturalism’.

In reality, colonial conquest historically benefited poor white Britons, as well as the ruling classes. As Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson note, poor white Britons ‘were encouraged to believe in their economic, political and racial superiority to the rest of the subjects of empire. This helped deflect attention from their own precarious position in the economic structure’. Further, their wages could rise because there were colonial populations to exploit. Aditya Mukherjee has shown how accumulation by colonial dispossession allowed for the betterment of economic conditions for the entirety of the metropole, including poor white people.

The process of primitive accumulation in capitalism or the initial phase of industrialisation is a painful one as the initial capital for investment has to be raised on the backs of the working class or the peasantry. To the extent that Britain and other metropolitan countries were able to draw surplus from the colonial people, to that extent they did not have to draw it from their own working class and peasantry. That is one reason why colonialism is supra-class, it is not only the metropolitan bourgeoisie exploiting the colonial proletariat but the metropolitan society as a whole benefiting at the cost of the entire colonial people.

Britain’s impending departure from the EU now sees it turning once again to the Commonwealth. It is no coincidence that Nigel Farage, MEP and former leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), expressed a preference for migrants from India and Australia as compared with East Europeans, and has advocated stronger ties with the Commonwealth. Theresa May, in her speech on the government’s plans for Britain’s departure from the EU, referred to the Commonwealth as being indicative of Britain’s ‘unique and proud global relationships’, and declared it was ‘time for Britain to get out into the world and rediscover its role as a great, global, trading nation’. At the same time, paradoxically, spokespersons of the Leave campaign adopted the language of ‘national liberation’ resulting in the reframing of Britain’s voluntary decision to leave the EU, an organisation it willingly chose to join, as ‘an existential struggle between oppressor and oppressed’. In reality, since the Leave vote, Britain’s appetite for imperial mythology and fantasy has grown. Boris Johnson, former Conservative Foreign Secretary and current Prime Minister, claimed in his first major speech following the referendum that, ‘Brexit emphatically does not mean a Britain that turns in on herself’. As he romanticised Britain’s long history of intervention in Afghanistan, he euphemistically descried British colonialism in terms of, ‘astonishing globalism, this wanderlust of aid workers and journalists and traders and diplomats and entrepreneurs’. He wondered whether, ‘the next generation of Brits will be possessed of the same drive, the same curiosity, the same willingness to take risks for far flung peoples and places’. Johnson’s dressed up Britain’s colonial history as being that of a small island nation’s attempt to do good in the world. He promised that a post-Brexit Britain will be ‘more outward-looking and more engaged with the world than ever before.’

Yet, the prospect of Britain retaining its status as the leading global power in the face of the defeat of its empire was presented by British politicians in 1961 as a major reason in favour of joining the EEC. Britain’s profound colonial amnesia and imperial ambition now see it making a drastic manoeuvre away from the EU. Considering the Leave vote’s embodiment of a rejection of anyone considered to be a migrant, a post-Brexit Britain promises to be a dangerous place for racialised people and those without a secure status. We urgently need new strategies for organising collectively in the service of anti-racist and migrant solidarity.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSE Brexit, nor of the London School of Economics.

In hindsight its amazing how close the vote was with the media swinging behind voting out and the longest period of austerity.

Vote leave could promise anything and fear monger their way to victory.

Which they did very cleverly.

Highlights how any vote such as bringing back capital punishment should never go down the same path.

The people of the U.K. are possibly the least racist in the world. Uncontrolled immigration policies benefit neither the immigrants nor the majority of those who are told to accommodate them. The so called liberal middle class want open borders for cheap labour and to cleanse the confected colonial guilt perpetrated by the writer.

“Arkadiusz Jóźwik was beaten to death in Essex, having reportedly been attacked for speaking Polish in the street.”

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-essex-41202493

“Patrick Upward QC, mitigating, said Mr Jozwik’s injuries were caused by him hitting the ground and not from the punch itself. “The deceased and his companion, according to the witnesses called by the prosecution, were staggering from drink,” said Mr Upward. “They made racist remarks to the youngsters, then invited violence from them, and they were considerably bigger and stronger than the young people.”

I have read in one place that the youngsters were a group of mixed race youths.

The sentence quoted above from this article includes the phrase ‘having reportedly’. There was a lot of reporting after the referendum which characterised everyday crime as racist because the victim was not white British. Another widely reported example was a brick thrown through the window of a Polish shop. It turned out that this was just a smash and grab and the fact the shop was Polish was just coincidental.

It is disgraceful that the writer should imply above that Arkadiusz Jóźwik was beaten to death when he was killed by a single blow. The writer has too readily accepted unsubstantiated journalism because it fits her narrative. She should perhaps look at her own prejudices before she attributes prejudice to others.

Reading the article, I do not see how EU is linked to colonialism. No demonstration, just one assertion. A weak argument. Individual countries were colonialiste in their past.

You have similar level of exclusion in India, recent resurgence of Hinduism in society. Same in China with non main ethnic population or in Japan with Ainu…

Every society generates exclusion. It remains true that colonialism was a monstrous abomination but not limited to Europe, see Japanese history, moghol history, US recent history… Turkish empire… And so on.

In each and every case, colonization was about the imposition of power and taking wealth.

Fortunately, as a Senior Lecturer, the world is your oyster. Lots of people are migrating all the time. I left Europe when I was 19. I went to Australia, North America, back to Europe often, now live in New Zealand for a while. All legal and above board.

As for migrant solidarity, if migrants don’t appreciate the country they have entered and have been allowed to stay, almost without exception by their own free will, they should not abuse the hospitality of their hosts by waging cultural warfare.

As an aside, although not in favour of communism and national-socialism, not to be confused with social nation-state democracy, one thing I liked about Mao and the earlier stage of the rise of Hitler, reading about it, was the way they re-organised society. That said, it was of course never worth the price the people in China and Europe later paid for the evil done by their regimes. One of the things that builds character most is good honest and sustained physical labour when people are young. If people have missed out on that, and moreover have never had to compete for a real job and work in productive endeavour to earn their keep, some kind of mushing of the vital organs seems to result, leading to strange and unrealistic notions about what these people think themselves entitled to. That said, many migrants have a hard time establishing in their new country, but that should make them wiser, not breed a culture of resentment and free entitlement.

It seems that if there is freedom of speech combined with easy living, such as has been the case for many people in the West for a considerable time now, the system which affords such ease and comfort is being broken down from within by some kind of collective mental deterioration. Then it is easy for outsiders to overthrow the reigning culture-Natural Law.

Maybe a good subject for a semester or two of lecturing?

So the UK is moving from a system where immigration status is determined based on their ethnic origin (predominantly white European) to an immigration system based purely on ability. Anyone who cares about racism should view that as a massive improvement.

While acknowledging the thrust of the article I felt that the definition of the EU as consolidating European colonialism did a disservice to the overarching point being made. Noting that it’s true that many of its founding members had a colonial past, the origin of the project is to be found in attempts at post-war rebuilding and reconciliation rather than any hankering after empires. And latterly, of course, it is very hard to identify modern members of the EU (say Poland, Finland, Ireland, et al) with the colonial past. On the contrary – these are nations that resisted the very concept. But that doesn’t hugely detract (though it distracts) from the very valid observations as to the root causes of Brexit and the intransigence shown in the current trade talks.

Gopal’s counter history destroys this narrative, demonstrating instead how enslaved and colonised peoples were the agents of their own resistance and freedom.

Paulo Freire’s hypothesis about the oppressed teaching their colonizers humanity is evident in this finding by Gopal.