Katy Hayward explains why the British government continues to gaslight Northern Ireland when it comes to Brexit. She argues that London needs to tread carefully when it comes to the democratic consent of Northern Ireland.

The much-anticipated (well, in some small circles) UK government command paper on its ‘Approach to the Northern Ireland Protocol’ has landed. Along with it, a statement by the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster in which he managed the tricky task of contradicting and affirming the Prime Minister’s comments on Protocol. ‘Although there will be some new administrative requirements in the Protocol’, he acknowledged, ‘these electronic processes will be streamlined and simplified to the maximum extent’. As Gove told an MP who recalled that Johnson had told NI businesses to throw Protocol-related paperwork in the bin: it is all to be done electronically, so ‘there is no need for bins’.

Even though the command paper brings some necessary (if not welcome) confirmation of the implications of the Protocol (not least for trade within the UK internal market), there is a habit of the British government’s approach to Northern Ireland that seems hard to shift. This is a habit of gaslighting, i.e. deliberately manipulating us into doubting our own sanity.

It was in evidence in Viscount Younger’s response on behalf of the government to the Ulster Unionist Party’s Lord Empeyon Monday: ‘Can I be clear that we’ve always been clear that there will be requirements for live animal checks and agri-foods [sic] building on what already happens in Larne and Belfast, as the noble Lord will know.’ Far from ‘always being clear’, the position of the UK government has been so confusing that politicians from all sides feel as though they have been ‘consistently misled’ on the matter.

And there is a risk that it can happen again, and to a much more serious degree. In the command paper, the UK government is steering dangerously close to being deliberately misleading on a matter of grave importance, i.e. the nature of the Protocol itself and of the capacity of Northern Ireland’s electoral representatives to determine its future. In an effort to assure unionists in particular, the impression being given is that, if they don’t like the Protocol, they can invest efforts into getting rid of it via the ‘democratic consent’ vote provided for in Article 18.

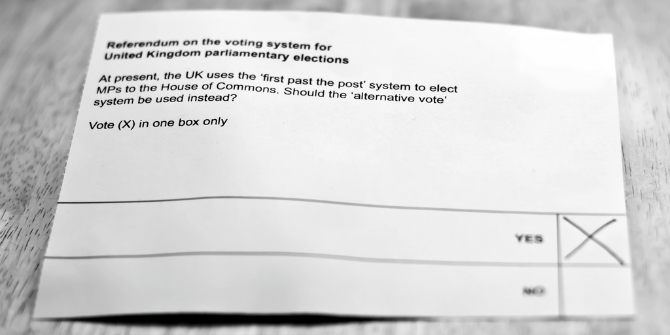

The inclusion of Article 18 was itself an effort to assuage concerns in Northern Ireland (particularly those of unionists) that they would have no say over the Protocol. Four years after the end of the transition period (and potentially every 4 or 8 years hence), Northern Ireland’s MLAs will have a vote on the continued application of Articles 5-10 of the Protocol, i.e. those relating in the main to the regulation and movement of goods. The process for this vote has been set out by the UK government in a Unilateral Declaration that accompanied the Protocol.

This consent vote has been given an extraordinary status in the UK government’s command paper. There is a danger that – even worse than being fuel for the future gaslighting of Northern Ireland (‘we were always clear it only applied to six articles’’’’, etc.) – the consequences of presenting the consent vote in the way that it does here are destabilising and entirely counterproductive to the type of ‘consensual and pragmatic approach’ the government says it wishes to see.

This is exemplified in paragraph 4, which I analyse in some detail here. It begins by describing the Protocol as a ‘practical solution to avoiding a hard border on the island of Ireland, whilst ensuring that the UK… could leave the EU as a whole’. It ‘necessarily included’, the paper states, ‘special provisions which apply only in Northern Ireland, for as long as the Protocol is in force’ (emphasis added).

This is misleading in a fundamental way: the Protocol will never not be in force; even if there is a ‘No Deal’ at the end of transition, the Protocol still stands. And, what is more, there are many aspects of it (e.g. articles on the protection of rights, safeguards, and the Common Travel Area) that will apply regardless of how a majority of MLAs fall in a future ‘consent vote’.

Paragraph 4 goes on to state that the special provisions for Northern Ireland ‘is why the democratic principle at the heart of the Protocol is so important’. The consent vote is a pretty miserly offering as far as democratic principles go.

The Foreword to the paper by Michael Gove draws a direct line of continuity between the consent given to the 1998 Agreement and that in the Protocol. Consent to the 1998 Agreement came on the basis of multiparty talks among elected representatives followed by a published document that was then subject to referendums in Northern Ireland and Ireland. The Protocol arises from Brexit (which was voted against by the majority of people in Northern Ireland) and from a compromise which was negotiated at the highest levels, voted against by all Northern Ireland’s MPs when ratified by the UK Parliament in an Act for which consent was withheld by the Northern Ireland Assembly. It is hardly comparable.

That is not to say that it is not important for the implementation of the Protocol to have the ‘broadest possible support across the community’ – of course it is. But this support is best fostered and created through proper and meaningful democratic scrutiny, representation and legitimacy. The consent vote is no substitute for that. Colleagues and I have recently written a report on this topic, and make some recommendations as to how to address this democratic deficit for Northern Ireland. The way that the UK Government has framed the consent vote in this paper only diminishes the chances of the Protocol commanding support across Northern Ireland.

Encouraging the delusion that the fate of the Protocol lies in the hands of Northern Ireland, Paragraph 4 continues: “The Protocol is not codified as a permanent solution; it is designed to solve a particular set of problems and it can only do this as long as it has the consent of the people of Northern Ireland. That is why it is for the elected institutions in Northern Ireland [i.e. the Assembly] to decide what happens to the Protocol alignment provisions in a consent vote that can take place every four years.”

Far from ‘determin[ing] the way forward in the longer term’ (as claimed in paragraph 14 of the paper), if MLAs vote to align to UK rules, it will be for the UK-EU Joint Committee to decide what happens for NI trade with EU and with GB, i.e. on NI’s land and sea borders. This would be to hand the biggest decisions about NI’s economy back into the hands of an unelected body which only needs to meet once a year and which does not need to publish its agenda or its minutes. And to which NI Executive would only be invited to attend as observers. Hardly a democratic coup.

In the meantime, the UK government is encouraging the belief that MLAs and voters have the capacity to see the end of the Protocol: ‘Only elections in Northern Ireland and the vote of the Assembly will decide the outcome’. Not only is this untrue (as discussed), this is dangerous. The presumption is that unionists will lead the charge on this, in order to defend the Union; with nationalists defending the open Irish border. There was always a risk of the consent vote being a proxy ‘border poll’. Now it is being used to raise the stakes even higher in every Assembly election.

Meantime, the real-world challenges of the Protocol and of Brexit will need to be faced and addressed by those same elected representatives. And this can only be done on a collaborative, cooperative basis.

As for the UK government, the fundamental question remains, more pressing than ever: What will it do to ensure that the democratic principle really is at the heart of its approach to the Protocol and, indeed, to Northern Ireland.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Katy, what the London government is doing is the best approach for the island of Ireland. It is letting NI go so that it can build its relationship with RoI. Its time for NI to be treated like an adult and not like a dependent.

If the UK government is really “letting NI go” and “treating it like an adult” then it would be much better for everyone if it just came out and said so. But it doesn’t, so it probably isn’t. Economically, it might like to, but politically the Unionists in NI and England would have conniptions.