In the third part of his nine-part series on the history of Brexit, Tim Oliver (Loughborough University London) looks at six objects through which we can understand why the Leave campaign won.

Why the Leave campaign won remains one of the most debated questions in British politics. That’s because there is, of course, no straightforward answer. The six objects through which the story of Leave is told look for answers in the UK’s constitutional setup, the successful messengers and messages (especially on immigration) of the various Leave campaigns, the role of a largely Eurosceptic press, and how the topic of Brexit worked its way deep into the issues that divide British society.

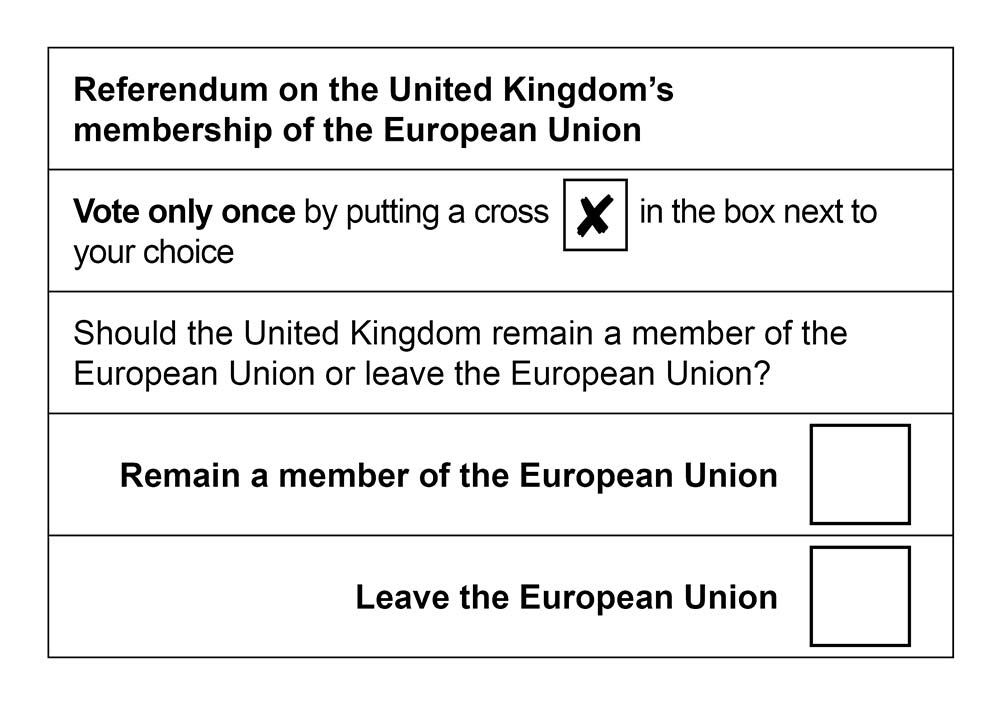

Object 7: A 2016 EU Referendum Ballot Paper

This mundane, functional slip of paper might not be the most colourful or exciting object in the series. That would be to overlook the many controversies that lie behind this little slip of paper. More precisely, if every eligible voter had cast their vote then there were potentially 46,500,001 little slips of paper. The numbers themselves speak of them playing a part in a successful act of democracy. 33,577,342 eligible voters, or 72.21%, put their mark on this little slip of paper, a turnout higher than any general election since 1992. Unlike in general elections where voters in a small number of marginal constituencies decide the overall result, everyone’s referendum vote matters equally. No surprise then that there was a noticeable increase in turnout in safe seats where turnout had traditionally been much lower.

As in any vote, a small proportion – 25,359 or 0.08% – were invalid. Reports tell the usual tales of blank ballots, some spoilt by being covered in essays and rants, others showing drawings of genitals, or some with an extra box drawn in with ‘neither of the above’ or some other proposal written next to it. The job of administering, distributing, collecting, counting, and then storing the millions of ballots fell, as usual, to an army of thousands of local council workers with security provided by local police forces. Overseeing the whole operation was the Electoral Commission, the independent body tasked with everything from registering campaigners through to approving the wording of referendum questions.

The administration of the vote might have been undertaken in a neutral and independent way. The setting up of the referendum was anything but. Because of its uncodified constitution, Britain has few if any rules about how and when referendums are to be called. The decision to call a referendum is largely in the gift of the Prime Minister and governing party. As David Cameron found out, that doesn’t give the prime minister complete control. Unlike in a state where referendums are set up and run according to rules set down in a codified constitution, it is up to the UK parliament to authorise the exact limits and nature of any vote.

That means politics rather than the law can triumph, creating no end of political tensions. The Prime Minister can decide the timing of the vote. But Cameron wanted to avoid holding a vote mid-term when governments are usually at their least popular, needed to avoid a clash with regional and local elections due in May 2016, and had to finish the renegotiation he promised to put to the people in a vote before the French and German elections of 2017. The question of eligibility presented difficult choices. Extending the vote to 16 and 17-year-olds was strongly supported by Remain campaigners but opposed by Leave supporters who feared such voters would favour Remain. Given the traditional low turnout of younger voters it’s unclear if their votes would have made a difference to the eventual outcome. It would, however, have boosted the focus of the campaigns and media coverage on issues connected to young people and therefore their pro-European outlook. The decision to exclude EU citizens living in the UK might have made more sense were it not for the fact that Commonwealth citizens living in the UK were allowed to vote. UK citizens who had been resident elsewhere in the EU for more than 15 years were excluded despite a 2015 Conservative party election manifesto commitment to scrap the 15-year rule that denied UK citizens the right to vote in UK elections. There was no requirement for the result to be backed by a super-majority (such as two-thirds) as required in the constitutions of a number of other democracies.

These problems were as nothing compared to the biggest headache of all: whether the government and Parliament would be bound by the result. The idea of parliamentary sovereignty holds that there is no higher power in the UK than that exercised by parliament. Constitutional theorists have argued that this power remained in place despite Britain’s membership of the EU because Parliament voted to allow EU law to take precedence. It could therefore vote to reverse that decision. Whether it could vote to ignore the will of the British people as expressed in a referendum was less clear. In what would become a problem for many MPs, the votes cast were not counted in parliamentary constituencies but in districts and councils consisting of several parliamentary seats. It meant a large number of MPs were uncertain as to whether a majority of their constituents voted Remain or Leave.

While the 33,577,342 ballot papers told us who won, they could not tell us much more. By analysing the votes in the districts and council areas the referendum was administered through, psephologists and pollsters have been able to tell us much more about the distribution of the votes across the UK. But it was to pollsters that people turned for insights into who and why people voted as they did. The next five objects explain some of the reasons why a majority of those voters backed Leave.

Object 8: Nigel Farage’s Coat

David Cameron might have promised and then called a referendum, but if one man can be said to be responsible for making him do so then that man is Nigel Farage. The longest-standing and most effective leader of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), there can be little doubt that Farage affected change to UK and European politics far above his position as an MEP and leader of a party with little representation in Westminster. How was it that this man achieved so much with so little and grew to be loved and hated by so many?

Some clues lie in the coat he was associated with and often seen wearing while out campaigning. Decked out in his tan-coloured, knee-length covert (or Crombie) coat with dark velvet collar, he came across as two figures. One was the privileged, privately educated, Thatcherite former city trader who would look at home in the race horsing world from which the design of the coat emerged in the nineteenth century. The other reminded people of the TV characters of the market trader Derek Trotter – or Del Boy – of Only Fools and Horses or used car salesman Arthur Daley from Minder. Both were dodgy but nevertheless loved especially for their optimism and determination. ‘This time next year we’ll be millionaires’ was Del Boy’s cry. ‘This time next year we’ll be out of the EU’ must have sounded equally naïve and laughable for many years. It was rarely easy for Farage and he didn’t make it easy for himself. His heavy smoking and drinking took their toll on a body that had taken on cancer and survived an horrific plane crash while out campaigning in the 2010 general election.

His hard work, however, paid off. Farage slowly but successfully built a movement composed of Eurosceptics and those angry with the way the country was changing, whether that was because of immigration, wider social changes that were making the country more liberal and metropolitan, or who felt left behind and neglected. The party’s high-point was the 2014 European Parliament elections when UKIP became the first party since the Liberals in 1906 to beat the Conservatives and Labour to come top in a national vote. Always at his best while out campaigning, he was as at ease in pubs and clubs as he appeared in TV studios and the European Parliament. His domination of UKIP and the ‘old boys club’ way in which it was run meant it soon fell apart after the 2016 referendum not simply because the goal of Brexit had been achieved but because, as with Del Boy or Arthur Daley, the enterprise was largely a one-man show. That domination did make him one of the two messengers (we’ll turn to Boris Johnson later in the series) that outshone David Cameron giving the Leave campaigns such a powerful boost. His message, and especially the anti-immigration stance that led to him being labelled a ‘Pound Shop Enoch Powell’ repelled as many as it attracted. Nevertheless, UKIP and the movement he worked to build provided an army of volunteers and supporters for the 2016 campaign that had not been available to the Eurosceptic campaigns in 1975.

Object 9: The Vote Leave Bus

One of the objects people immediately think of when the 2016 referendum comes to mind is the bright red Vote Leave campaign bus. It was one of the most prominent symbols of the entire campaign, appearing repeatedly in media appearances as it toured the UK and stoking much controversy – and therefore the sought for attention – because of the messages emblazoned on its side. On board were to be found many of the leading Vote Leave campaigners such as Conservatives Boris Johnson and Michael Gove and Labour’s Gisela Stuart. They were sometimes accompanied by many of the campaigns leading organisers such as Matthew Elliot and Dominic Cummings.

The bus chosen was a Starliner, a luxury team coach built by Neoplan Bus GmbH, a German bus company. Few will have seen the interior, which contained the usual air conditioning, multiple screens, DVD and CD/MPS player, fridge and boiler. Built in Germany and Poland, Remain campaigners made much of the fact that Vote Leave was using a German-Polish bus that was the product of pan-EU industrial cooperation. Had the UK been outside the EU then the necessary tariffs would have added thousands of pounds to the cost of importing such a bus, they claimed.

More than anything the bus revealed two things about the Leave campaigns. First, that there was no single Leave campaign. The same can be said of the Remain campaigns where Britain Stronger in Europe, the official Remain campaign, was surrounded by and sometimes had to compete with a host of smaller groups. The division within the Leave camp was much more obvious. On one side was Vote Leave, closely connected to Conservative Eurosceptics but with some cross-party appeal. On the other was Leave.EU, more closely connected to UKIP. Relations between the two were sometimes so strained that when the Electoral Commission decided to make Vote Leave the official campaign group, Aaron Banks, a prominent Eurosceptic and leading financial backer of UKIP, threatened legal action. Dominic Cummings even claimed that Nigel Farage’s toxic image amongst some floating voters cost the Leave campaign votes. The division, however, turned out to be an advantage by allowing the Leave campaign to pursue, albeit in an uncoordinated way, a flanking manoeuvre on Remain. One flank was led by Vote Leave, with its famous (or infamous, depending on your point of view) bus leading the attack. On the other was Leave.EU. While the two pushed some common themes such as immigration or sovereignty, Vote Leave with Johnson and Gove offered a message that was more liberal and appealed to voters put off by Farage’s more toxic image and more nativist message. Johnson and Gove were also able to present something of an appearance of a government in waiting without having to put forward a fully costed manifesto and promises they could be held to. It left the Remain campaigns fighting on too many fronts. While the division helped secure victory for Leave, it left doubts about what exactly Leave was supposed to mean in practice.

More infamously, the Vote Leave bus is remembered for one of the messages emblazoned down its side. ‘We send the EU £350 million a week. Let’s fund our NHS instead.’ The figure was roundly dismissed by the Office for National Statistics and various experts. The NHS complained to Vote Leave over its illegal use of the NHS’s logo in the message. The complaints were ignored. Instead, as Vote Leave hoped, the controversy and every complaint only served to reinforce the message by repeating it. All some voters heard was ‘£350 million a week for the NHS’, which matters a lot in a country where the NHS has been described as the closest thing to a national religion. As Charles Grant of the Centre for European Reform and a leading Remain campaigner noted, Vote Leave ‘exploited the fact that in political advertising, unlike commercial advertising, there are no penalties for untruths’. Fewer complaints were made about the other message on the bus: ‘Let’s take back control.’ As we turn to later in the series, that message was one the Remain campaign struggled to rebut. Who could reject the idea of having more control? But as with the NHS claim, the detail was less clear. Who would have control? Would it be Parliament, the government, devolved bodies or would there be more direct democracy? How much control would there be for the UK in a globalised world where the EU is a regulatory superpower? And over what would Britain gain control?

Object 10: A Polish Shop

If there was one thing more than any other that Vote Leave’s ‘Let’s take back control’ message was about it was immigration. Of all the reasons to explain why Leave won the referendum, immigration can be put forward as the predominant one. In focusing on immigration, the Leave campaigns were playing to a receptive British public. Polling showed that at the beginning of 2016 immigration overtook the economy as the number one issue of public concern. While it was not the only form of immigration that some voters were motivated by – immigration from outside the EU will be covered by a later object – the issue of people moving to the UK from Central-Eastern Europe was one of the most prominent issues.

The appearance – or increase in the number – of Polish shops in towns and cities across the UK was one of the clearest signs of the numbers of people who moved to the UK from Central-Eastern Europe. That mainstream retailers such as Tesco soon took notice, with supermarket chains introducing Polish food to the aisles of many of their branches, showed how big a market had begun to appear. When in 2004 the EU enlarged to include ten new members – its largest-ever enlargement – the UK, along with Ireland and Sweden, were the only Member States to impose few if any temporary restrictions on free movement. The then Labour government failed to predict accurately the number of new arrivals. A report produced in 2003, which assumed all other EU Member States would open their labour markets, estimated an increase of between 5,000 and 13,000 net immigration per year. The Office for National Statistics later estimated that between 2004 and 2012 the net flow of migrants from the new Member States to the UK was 423,000. But this was only part of a much larger increase in immigration. It’s estimated that between 1997 and 2010, net immigration to the UK quadrupled. A total of 2.2 million people arrived from elsewhere in Europe and the rest of the world. The UK economy had grown over the same period in no small part thanks to being open to large numbers of high skilled, high paid workers and low-skilled, low paid workers.

The effects of immigration were felt in varied and often unique ways. Cities such as London or Manchester soaked up new arrivals from all over the world, as they have done so for centuries (albeit not without racial, social and political tensions that have in the past turned into riots). Areas of the UK that saw immigration go from nothing to record levels, however, saw a backlash in attitudes towards immigration. More worrying for pro-Europeans was the imagined influx in areas to which immigrants did not move. Studies have pointed to how a large number of Leave voters lived in areas that had not seen large levels of immigration and therefore few if any such changes such as the emergence of Polish shops. It was the imagined influx, as seen on TV or heard about in the pub, that worried these voters.

It was to try and tackle this growing political unease that in the lead-up to the referendum Cameron sought, in his renegotiation of the UK’s membership, some way to limit the right of citizens from elsewhere in the EU to move to the UK. Back in 2010, Cameron had said he wanted to see net immigration to the UK drop below 100,000 a year. The figure became a deadweight around his neck as his government repeatedly failed to achieve it. Incapable of limiting free movement from the rest of the EU and desperate to maintain a UK economic model that continued to draw on the brightest, best and cheapest workers from all over the world, he was never able to get the UK even close to the figure.

The Leave campaigns were able to draw on these concerns about immigration with regard to security, identity, welfare, cost, border control and, thanks to Cameron’s failure to deliver the 100,000 target, the repeated failures of government. One of the most powerful and controversial claims of the Vote Leave campaign was that Turkey was poised to join the EU. Successive UK governments had supported Turkey’s decades-long application for membership, although membership itself had never seemed to get any closer. To Vote Leave, however, the possibility of a country of 76 million people that neighboured Syria and Iraq (both of which were highlighted in slightly different colours on an official leaflet to draw attention to them) was used to play on a number of fears and concerns about immigration. Cameron’s failure to secure a radical change to the UK’s immigration policy vis-à-vis the EU, with only small technical changes achieved, reinforced a message from Leave campaigners that an enlarged – and potentially still enlarging – EU could not be changed. It merely reinforced an image of an EU that would not change and a UK government beholden to it and unable to deliver what they claimed the people wanted.

Object 11: A J.D. Wetherspoon Brexit Beer mat

How can we measure the success of Britain’s vote to Leave? Is it even possible to measure something as complex as Brexit? Can the focus be on the promises made by the Leave campaigns? Should the focus be on the jobs or wealth lost or created? Would bringing net immigration down to under 100,000 a year be the goalpost? Is it a success if the UK ‘takes back control’? Is success to be in the quality of the new relationship negotiated between the UK and the EU? But that relationship is a means to an end and it’s not clear what end that is. Is it to be defined by Britain’s place in the world? Is it to be about the UK’s political economy, which some Leave campaigners felt had become too open and globalised while other Leave campaigners believed was not open enough because it was hamstrung by the EU? In his book WTF, journalist Robert Peston argues that a successful Brexit is one that addresses the causes of the Leave vote. To some journalists, there was one venue they felt they could turn to in order to identify what motivated Leave voters: a local J.D. Wetherspoon pub.

Since its founding in 1979, Wetherspoon’s has become a popular chain of about 900 pubs. With no music, an unpretentious feel and reasonable prices, they can be found in some of the richest and poorest areas of the UK. Whether one likes or frequents a Wetherspoon pub, however, can be a divisive topic. In part that comes down to how some people feel about chain pubs and the way Wetherspoon pays its workers and suppliers. Brexit, however, has also become one of the reasons why some now avoid the chain while others hale it. Tim Martin, its founder and chairman, has been a vocal and leading supporter of Brexit, donating large sums of money to pro-Leave campaign groups and during the campaign even allowed the chain’s beermats and magazine to push a pro-Leave message. That continued after the referendum with Martin supporting a no-deal Brexit. He even went so far as to undertake a ‘Free Trade Tour’ of 100 of his pubs to speak about why a no deal was the best outcome.

While pubs, clubs and cafes have long been the sight of political debate and almost every politician at some point is pictured pulling a pint at a local pub, such a dramatic and deliberate attempt to push the most divisive topic onto punters enjoying a quiet pint might appear to be a dangerous stunt that could easily backfire. Sensing the potential for backlash led many other business leaders to shy away from becoming involved. There were exceptions such as James Dyson with his support for Leave and Richard Branson backing Remain. Many others, especially those connected to financial services, were wary of any involvement. Those in The City were especially conscious of continued public hostility to banks and multinational firms following the 2007 financial crisis, recession and the austerity that followed. As we turn to in the next part of the series, this made life extremely difficult for a Remain campaign built largely on an economic case for membership.

Is the local Wetherspoon pub the best place to go to find out what motivated Leave voters? There are many reasons to doubt this. As Martin himself points out, his pubs remain popular in both Remain and Leave-voting areas and they have seen no obvious decline or surge in sales because of his political positions. What Wetherspoon can show is how deep and divisive the issue of Brexit became that it worked its way into the life of one of the UK’s most popular pub chains. It did so not simply because of concerns about free trade, sovereignty or immigration, important though they were. It did so because the referendum also became a vote about a host of issues – many of which we turn to in later objects – that families, friends and work colleagues often argue about and discuss over a pint in their local pub.

Object 12: The Sun: Up Yours Delors!

The British media, especially the printed press, has for a long time been heavily Eurosceptic. Amongst the many Eurosceptic headlines the British press has produced, that of The Sun on Thursday 1st November 1990 is amongst the most infamous and, given the date, a taste of what was to come. ‘Up Yours Delors’ it shouted on its front page. ‘At midday tomorrow Sun readers are urged to tell the French fool where to stuff his Ecu.’ Jacques Delors, the then president of the European Commission, was on the receiving end of such vitriol not only because of his support for the Ecu (the European Currency Unit), which was a forerunner of the Euro. For Delors, the Europan single market, championed by many Thatcherites because of its emphasis on competition and the free market, would need to be balanced by a social Europe. That angered some within the Conservative party, still then led (albeit only until the end of November 1990) by Margaret Thatcher. The article itself contained crude but familiar complaints about dodgy European food, the plot to replace the pound with the Ecu, that British beef was unfairly banned because of false claims it contained mad cow disease (claims that were, in fact, true) and, worst of all, because France had capitulated to the Nazis during the Second World War when Britain stood firm.

Should it, therefore, have come as a surprise when twenty-six years later many of the UK’s newspapers supported Leave? In the intervening years, UK newspaper readers have been told that the EU – or ‘Europe’ – planned to ban kilts, double-decker buses, curries, charity shops, bendy bananas, the British Army and many, many more things. Even the 2011-12 Leveson Inquiry into the culture, practices and ethics of the British press documented a wealth of misleading claims about the EU. Boris Johnson himself started his career as a young reporter in Brussels where his reports, while entertaining, exaggerated or were simply misleading about EU laws, regulations and policies. To be fair, for all the Euroscepticism in its press the UK has also been home to the likes of the FT and The Economist, famed for some of the best EU and international coverage. Parts of the UK media might engage in xenophobic coverage of the EU, but most of the press lacks the uncritical deference that some media elsewhere in the EU can show towards European integration. Nevertheless, when faced with a largely Eurosceptic press British politicians, especially Conservative ones, had long felt it best to play along and score easy points by attacking the EU.

While some newspapers did support Remain, that the majority of Conservative-leaning publications did not seem to come as a surprise to Cameron and his advisers. Being Conservatives, they had rarely had to face head-on the full might of Britain’s Right-leaning press. As Labour and other part leaders knew only too well, that had normally been directed towards them. It meant Cameron and Conservative Remain campaigners had no way of adequately coping with the barrage of attacks and criticisms fired in their direction from the very start of the campaign.

As required by UK law, broadcast media such as the BBC and ITN were more impartial. That, however, created a host of new problems with the BBC especially risking the ire of either side. Remain campaigners complained that in seeking to be impartial the BBC always offered a space and equal time to the opposite argument, irrespective of how accurate it was. Leave campaigners could be heard often complaining that the BBC was part of a left-wing metropolitan elite. No such limits were found online. Despite many young people being pro-Remain, the campaign online and in social media was dominated by the Leave campaigns. This reflected how across the Western world populist and Right-wing parties had moved quicker to organise themselves online. Whether this was boosted by foreign interference and illegal data gathering will be the topic of an object later in the series.

In the face of such a daily torrent of Euroscepticism, it is perhaps remarkable that in June 2016 only 52% of voters said ‘Up Yours’ to the EU, Cameron and whoever and whatever else it was that drove them to vote Leave. Why, in a country home to such high levels of media and political Euroscepticism did 48% of those who voted still opt to Remain in the EU? Just as there is no simple answer to why Leave won, there is also no simple answer to why 48% voted Remain. The story of Remain will be the focus of our next six objects.

If you’d like to suggest an object for this history of Brexit then please do so through the comments section below or by email (t.l.oliver@lboro.ac.uk). At the end of this nine-part series I’ll publish a selection of the objects you suggest. Thank you to those of you who have already done so.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image by Daniel Naczk, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Let’s play with numbers a bit.

“The question of eligibility presented difficult choices. Extending the vote to 16 and 17-year-olds was strongly supported by Remain campaigners but opposed by Leave supporters who feared such voters would favour Remain. Given the traditional low turnout of younger voters it’s unclear if their votes would have made a difference to the eventual outcome.”

I have read that there were at the time of the referendum about 1.7 million 16-17-year-olds who could have voted had the age limit been lowered. Assuming that of the 80% would vote, and 80% of those who voted would have voted Remain (I think these two numbers would have been very much at the high end of expectations for the Remain campaign), this means that the Leave majority of over 1.2 million would have been reduced by 80%*60%*1.7 million, or about 850 thousand, and assuming everyone over 18 would have voted the way they did vote, the 16-17-year-olds could not have changed the overall result, though they might made it a lot narrower.

“UK citizens who had been resident elsewhere in the EU for more than 15 years were excluded despite a 2015 Conservative party election manifesto commitment to scrap the 15-year rule that denied UK citizens the right to vote in UK elections.” According to this page https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn05923/ the total number of UK citizens registered to vote overseas in 2016 was about 264 thousand. I can’t believe that scrapping the 15 year rule would have more than doubled that. After all, the longer people are out of the country the more they are detached from national politics (I know this from experience). It would of course have been blatantly unfair to let all UK citizens resident in the EU vote, but not elsewhere, so I think the percentage of those new voters voting Remain compared to those voting Leave would not have been that high. My guess would be about 2/3. So even scrapping the 15 year rule AND letting the 16-17 year olds vote would not have changed the result, all other things being equal.

I do wonder though why David Cameron did not try one tactic which I think might have been pretty effective, but which even Nigel Farage would have had a problem objecting to. Given the widely quoted number of about 1 million UK citizens living in the EU27 and the figure quoted above of 264 thousand registered to vote from the whole world, I presume that there were a large number of qualified UK citizens living in the EU27 who were not registered. Why didn’t the UK Government make more effort to get these citizens to register? Many governments, especially in the EU, have databases where they can easily find the addresses of all who register with UK passports. Surely many would have agreed to forward a get-out-the-vote package with, say, a leaflet on how to register and leaflets from Remain and Leave? I don’t think such an action would have changed the overall result, but it would have helped Remain.

But .. (I put this in a second message because it isn’t about numbers) David Cameron’s big mistake was that he settled on the wrong strategy from the beginning. In the Bloomberg speech (when he committed the Tory party to a referendum) he announced that he would seek a renegotiation with the EU27 and only afterwards decide whether to support Leave or Remain. I suppose he was influenced by Harold Wilson’s 1975 policy, but I can’t believe this was war-gamed at all, because a 5 minute chat with one of his political advisers followed by another 5 minute chat with Angela Merkel ought to have convinced him that the chance of finding a deal which would simultaneously satisfy the EU27 and the Tory newspapers was virtually zero. And indeed this whole policy was a major failure, as the renegotation was hardly mentioned during the campaign. It would have been far better for Remain had David Cameron and the pro-EU forces within the Tory Party got together with Labour and the Liberal Democrats much earlier to run a Remain campaign, identifying for example an Alastair Darling figure to front it. As it was, the two most effective Remain politicians were Ruth Davidson and Sadiq Khan, but they came onstream far too late to make any difference.

If David Cameron had really cared about UK staying in the EU, he would have taken more trouble, from the beginning. And then maybe the result of the referendum would have been different. But the whole story of Brexit is that there were hardly any passionate Remainers among the leading politicians, and that’s why Brexit has happened.

I wonder if the papers, Nigel Farage, David Cameron or anyone or anything else mentioned here caused the Brexit vote. There has been a simmering discontent in this country for a long time. London and the Financial Service Sector dominate this country’s economy ,earning 80% of it’s wealth.. No wonder there has been little interest, by successive governments in the rest of the country. Germany has a huge and respected manufacturing sector, and is the richest economy in Europe. France dominates Energy ,Transport, Manufacturing and Agriculture and Fishing.All EU countries seem to have a more balanced economy than ours Perhaps this is partly to do with our history, London has always been the centre and It has always been a World City, Even Dick Wittington and his cat felt the need to make their fortune in London Why would iLondon be interested in the rest of the country,the lost manufacturing industries, the dismal overpriced transport system , the selling out of our fishing industry, and so much else.So why would people who have lost heart not vote Brexit , for Boris Johnson and the possibility of change when many parts of the country are poorer now that 45 years ago when , in panic Britain joined the EU