What influence did the European Parliament have in the Brexit negotiations? How did Brexit affect the distribution of power inside the European Parliament? In this post, Edoardo Bressanelli, Nicola Chelotti and Wilhelm Lehmann analyse the role of the European Parliament in managing Brexit.

Politics and Governance has recently published a Thematic Issue on the consequences of Brexit for EU institutions, such as the Council of the EU and the Court of Justice, and transnational actors like interest groups or financial organisations. The Issue has shown that – while Brexit has been generally regarded as a threat to integration or a trigger of disintegration – the Union has been able to prepare itself for the departure of the UK.

We can speculate on the drivers of this institutional adaptation. The EU may seek to protect itself from the ‘malign’ influence of a soon-to-be third country. It may fear the organizational consequences of withdrawal and seek minimizing potential disruptions. It could be guided by the willingness to ‘punish’ disintegration and prevent further exits. Whatever the reason, one of the key findings of the project has been the capacity of the EU to adapt (so far) to the challenges posed by Brexit.

This conclusion stands also for the European Parliament (EP). In our article, we analyse two aspects related to Brexit and the EP: first, the role played by the EP in the negotiations of the Withdrawal Agreement and the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement; second, the influence of British MEPs in the Parliament during the Brexit period, from the referendum to Brexit day (June 2016–January 2020).

The EP and the Brexit negotiations

According to Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, the EP gets involved essentially at the end of the negotiation process between the EU and the departing state – when it has to give its consent to the withdrawal agreement that the two parties have signed.

However, in the case of the Withdrawal Agreement between the EU and the UK, the EP was able to increase its institutional powers and obtain a voice throughout the entire process. Not only was the Parliament kept regularly and thoroughly informed by the European Commission; it managed to participate in the key stages of the negotiations, becoming a ‘quasi-negotiator’.

From an organizational point of view, Brexit activities were mainly controlled by a close and senior group, the Brexit Steering Group, chaired by Guy Verhofstadt and composed of five political groups (all but the more right-wing Eurosceptic groups). The restricted composition of this body allowed the EP to engage in the political strategizing of the negotiations. It worked very closely with the EU Council and, particularly, with the Commission’s Task Force.

What influence did the EP have in the negotiations? As the EP, the Council and the Commission had very similar preferences, it is difficult to detect it precisely. In any event, the EP mainly focussed on citizens’ rights, strongly insisting on issues such as applications for permanent residency, work permits or travel regulations.

The next round of negotiations over the future relationship formally started in March and was completed on Christmas Eve 2020, when the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement was signed. Despite a more favourable legal basis, the EP remained quite peripheral in the construction of the EU position. Coordination between the EP and the Commission now concerned a much larger array of policies, hence the joint strategizing element was more difficult to attain.

We argue that this is (in part) related to how the EP organised itself for such negotiations. The Steering Group was contested within the EP, with an increasing number of actors asking for more transparent and broader participation. It was thus replaced by the UK Coordination Group, which incorporated MEPs from all groups (including the Eurosceptics); and the EP committees – largely side-lined in the earlier negotiations – were now given a much greater role. The broader composition of the UK Coordination Group and the greater involvement of committees reduced the political clout of the EP, making its involvement more ancillary.

From a substantive point of view, the EP aimed to reach an ambitious economic partnership with the UK, which would require the latter to remain aligned to EU rules in fields such as environment, competition, or labour standards. This stance was not particularly new (the EP had already expressed it during the earlier negotiations) nor particularly controversial within the EU. However, differently from the Withdrawal Agreement negotiations, the EP struggled to identify its key priorities, limiting its capacity to leave a significant mark on the Trade and Cooperation Agreement. A related problem was that in several committees MEPs were just trying to retain the status quo ante, not realizing the radically new situation.

British members in the EP: between Auld Lang Syne and glee

The EP not only tried to influence the negotiations but, well before Brexit occurred, it sidelined, to a large extent, the departing British members from its legislative work. The British delegation was traditionally considered rather influential within the EP. For instance, in their analysis of the 2009-14 period, Simon Hix and Giacomo Benedetto concluded that UK MEPs authored more reports than the MEPs from every other member state except Germany.

We assessed whether this conclusion was still valid in the period following the 2016 referendum when the UK members could start feeling the costs of their soon-to-be departure. Their parliamentary colleagues were more hesitant to attribute them a position of responsibility. Also, allocating senior roles and important legislative dossiers to the UK members could be difficult, as relationships with the UK had soured when the latter decided to leave the Union.

Empirically, we observed the Brexit impact on the UK delegation by mapping changes in the positions of power allocated to its members over time. First, we looked at the number of senior positions obtained by the UK delegation at the beginning of a new parliament and at mid-term, when the EP top offices (e.g. positions in the bureau, committee chairs) are reshuffled.

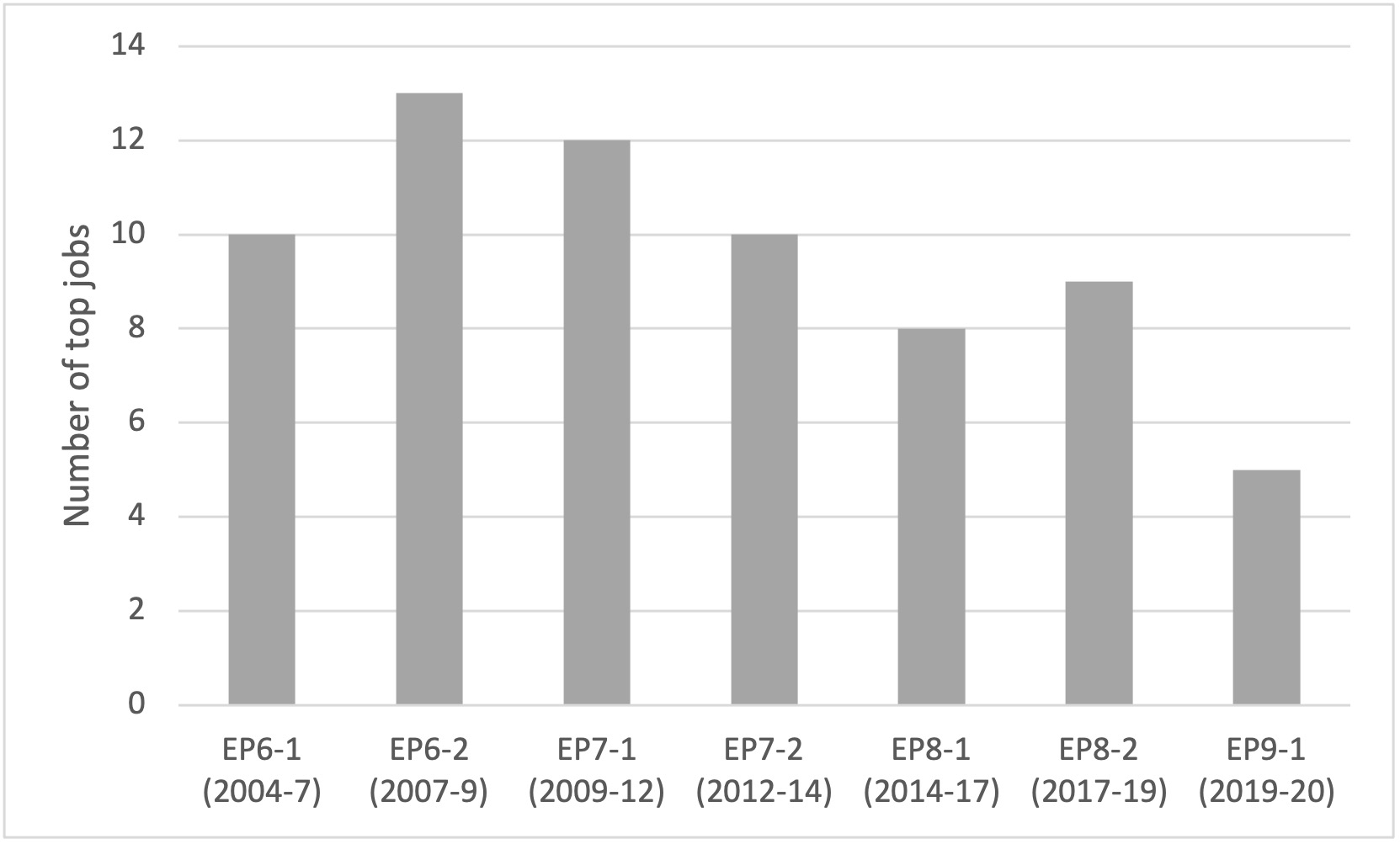

Figure 1: British members and top jobs in the EP

As Figure 1 shows, there has been a downward trend in the number of office positions obtained by the UK since the second half of the 2004–2009 Parliament, when the UK controlled a total of 13 positions, including two EP Vice-Presidents. The most dramatic fall is observed, unsurprisingly, in July 2019, at the beginning of EP9. The British delegation was only allocated five top jobs: two committee chairs and three committee vice-chairs, with no British member represented in the bureau. Clearly, EP leadership was hesitant to assign an institutional role to any British member.

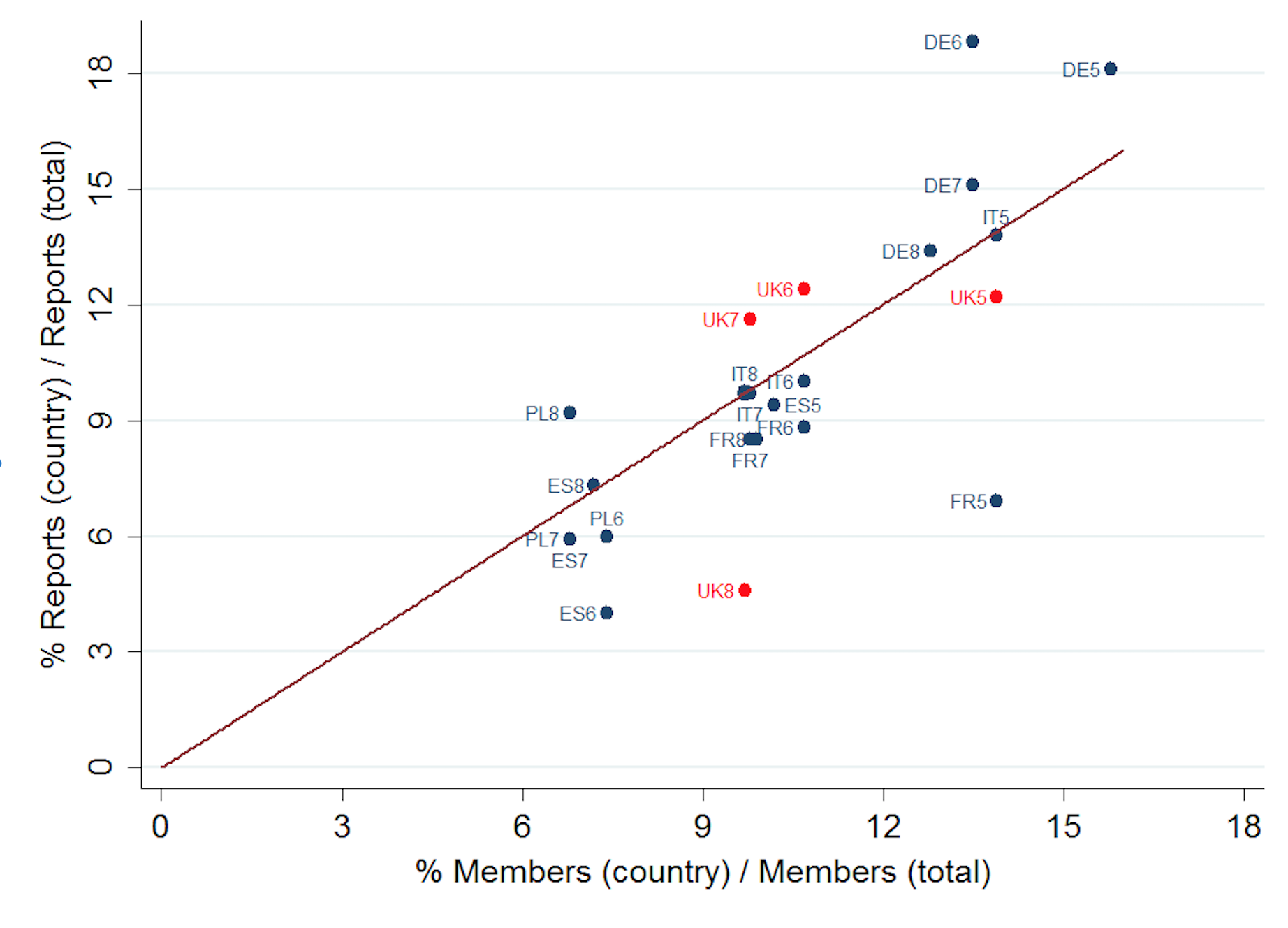

Second, we made a similar mapping exercise for the allocation of parliamentary reports, focusing on the more important legislative reports, agreed through the ordinary legislative procedure. We observe that the UK delegation used to do better than most other national delegations, with the clear exception of the German one. However, UK members elected in 2014 appear to have significantly underperformed when compared to their predecessors, having obtained only 4.6 per cent of the legislative reports while, in the previous parliaments, the share of reports has always been higher than 10 per cent. In part, this was due to the strong results of the UKIP party.

Figure 2: Legislative reports and the UK delegation

Source: Data on legislation collected by Reh et al 2020. Note: DE: Germany; ES: Spain; FR: France; IT: Italy; PL: Poland; UK: United Kingdom

Our analysis has shown that the process of Brexit affected the distribution of power inside the EP, limiting the institutional and policy-making role of the UK representatives even well before Brexit day. It has thus brought further evidence about the capacity of the EP to protect its institutional role and turf when facing adverse conditions.

This post represents the views of the author(s) and not those of the Brexit blog, nor of the LSE.

1 Comments