Global Britain should look towards supporting the development of Africa’s digital landscape, argue Pauline Girma and Oona Palmer (LSE). In this post, they explain that given that seven of the ten fastest-growing internet populations are located in Africa, and that it is home to what is the youngest population in the world, the future growth of the global e-commerce market depends upon unlocking the continent’s potential.

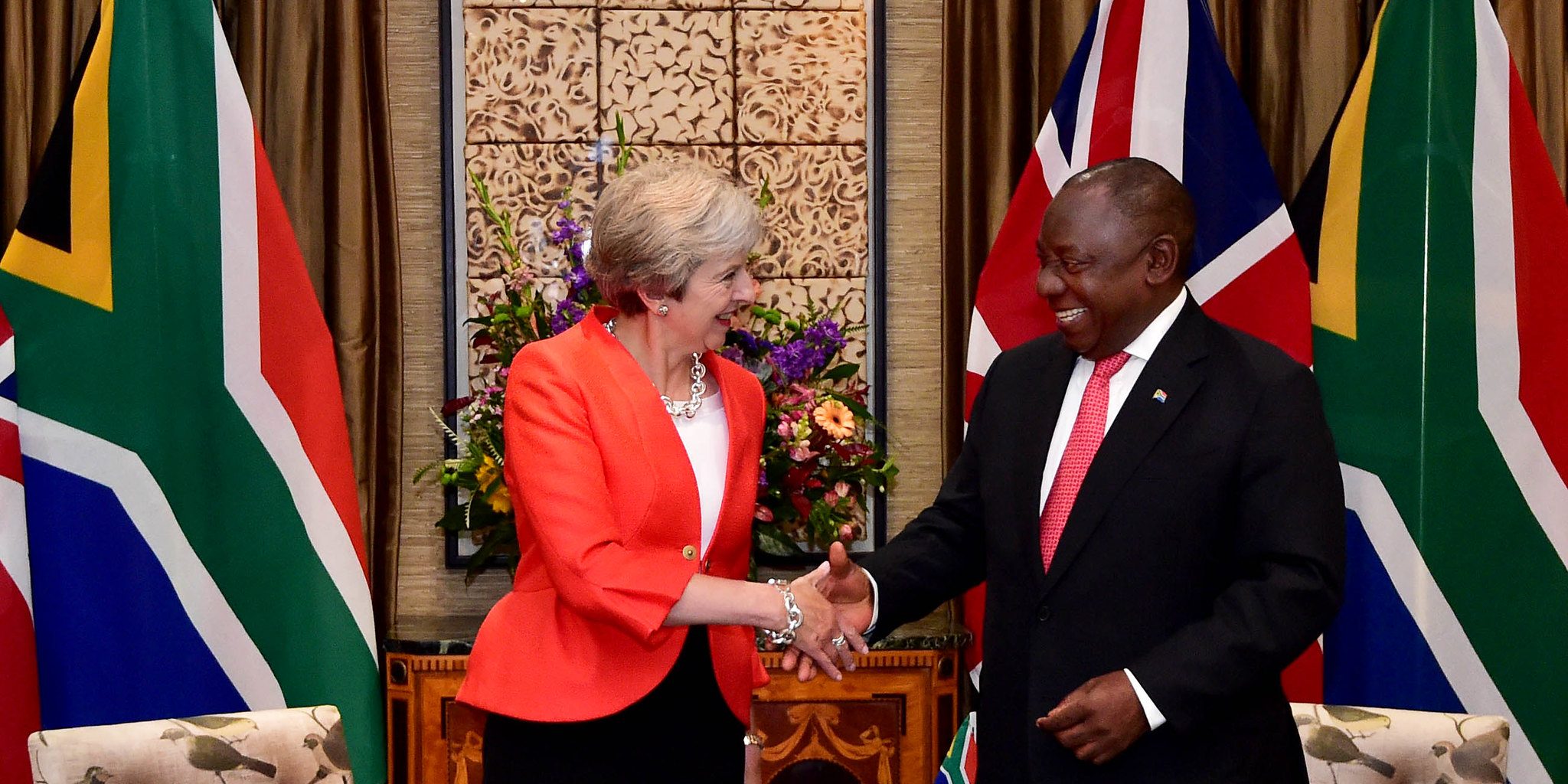

The British Prime Minister has invited President Ramaphosa of South Africa to join the G7 summit in Cornwall, England in early June. The summit will discuss among other things trade and the digital economy. A number of African states are taking part in the WTO negotiations on digital trade, but South Africa has opposed the whole idea of the current WTO negotiations on the topic.

Africa presents both significant opportunities and challenges for those looking to expand e-commerce. Despite changing demographics and improving business environments, which have contributed to rising household consumption, infrastructural and technical constraints continue to undermine efforts to scale e-commerce, and hinder Africa’s integration in the global digital economy. Fewer than a quarter of Africa’s roads are paved according to the World Bank, and even the relatively large markets of Nigeria and Kenya struggle with access to electricity. Moreover, the lack of widespread internet connectivity remains a fundamental barrier to the uptake of e-commerce in Africa, with less than one-third of Africans able to access the Internet. Yet the potential for the widespread adoption of e-commerce to facilitate technological ‘leapfrogging’ has led to a general recognition amongst African states that – if administered and regulated properly – e-commerce has the potential to become a powerful force for sustainable development and economic growth.

As Africa looks to ramp up e-commerce activity, it must address issues related not just to connectivity but to differences in access and adoption. Whilst Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa dominate Africa’s e-commerce layndscape, less than 5 per cent of the population in many smaller Sub-Saharan African states have made online purchases. These variations owe not only to discrepancies in internet connectivity rates, but also to cumbersome postal delivery services, fears of online fraud, and low penetration of electronic means of payments across Africa. Such barriers to the uptake of e-commerce have meant that cash-on-delivery remains the prominent way in which electronic transactions are paid for in the region. On top of these constraints, only a quarter of African countries have a population in which more than half of citizens have credit cards, with women generally being less likely to have bank accounts or access to online platforms. Alongside implementing reliable delivery services and payment systems to establish online consumer trust, ensuring that rural communities and women can adequately engage with online platforms will prove crucial to unlocking the potential for e-commerce in Africa.

Compounding infrastructural constraints is the overall lack of an enabling environment for digital trade and related activities to flourish. Whilst larger markets such as South Africa have put in place frameworks addressing concerns related to data privacy and cybersecurity, other African states have yet to define these parameters by ratifying and implementing the ‘African Union Convention on Cybersecurity and Personal Data’. This delay owes partly to their limited institutional capacities surrounding the implementation of the appropriate legislative and enforcement frameworks for e-commerce. Given that creating a digital ecosystem conducive to innovation, entrepreneurship and growth depends upon having a supportive regulatory climate that fosters transparency and investment, future efforts related to e-commerce must be directed towards promoting capacity-acquisition and targeted technical skills-building across the African region.

In light of the above constraints, bridging the digital divide (i.e. the gap between those with access to information and communication technologies and those without) has been a core priority shared by all African states. Nevertheless, divergent perceptions over how best to achieve this objective has led to disagreements over the relative merits and drawbacks of taking part in the WTO’s Joint Statement Initiative [JSI] on e-commerce, and the potential consequences of liberalising Africa’s e-commerce markets more generally.

On the one hand, most of the states represented by the African Group in the WTO have expressed their firm opposition to participating in the plurilateral negotiations on e-commerce, viewing the creation of binding global rules on e-commerce – such as the proposed rule to permanently extend the existing moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions – as “entirely premature”[4] and fundamentally incompatible with their underlying development needs. Instead, these states have conveyed a marked preference for pursuing a much more inward-focused digital industrialisation strategy, in the hopes of building the national digital capabilities that would enable them to effectively compete in the sphere of international digital trade in the future. Tied to fears of ‘digital colonialism’, their reluctance to engage in the JSI can largely be understood as reflecting ongoing frustrations over the failure of the Doha Development Round to deliver on its mandate. This is further exacerbated by the perception that the WTO has proved incapable of representing developing countries’ interests.

On the other hand, a handful of states within the African Group – including Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Kenya – have been more open to taking part in the e-commerce plurilateral initiative, approaching the JSI as an opportunity to contribute to the international e-commerce rule-making process and secure capacity-building assistance from the developed world. The latter is crucial given that only 1 per cent of all current funding provided under Aid for Trade programmes is being allocated to ICT projects, and multilateral development banks are investing as little as 1 per cent of total spending on ICT projects and related policy developments.

While positions regarding the JSI have been mixed, African states have generally adopted a cautious approach to international initiatives on e-commerce, with even those states that have chosen to opt into the JSI demanding that they receive ‘special and differential treatment’ (in the form of more time to implement agreed-upon provisions and capacity-building assistance) so as to ensure that their e-commerce markets are not pre-emptively liberalised. The recent decision to incorporate a chapter on e-commerce in the ‘African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement’ serves as an important milestone for Africa’s digital transformation strategy, reflecting both a shared recognition of the importance of addressing e-commerce-related concerns regionally, and an opportunity to strengthen African digital capabilities before fully committing to liberalising their e-commerce markets at the global level.

Overall, the growth of global e-commerce could either exacerbate the existing digital divide, or it could serve as a new engine for economic growth and development by enabling enterprises from Africa and the rest of the developing world to tap into profitable segments of international e-commerce markets. Seizing the development opportunities tied to e-commerce, however, will require investments in African infrastructure, digital literacy and skills, online payments services and digital entrepreneurship. The outcome of the JSI and whether it sufficiently promotes the digital inclusion of African stakeholders will serve as an important litmus test for how the global digital landscape will evolve in the next few years: given that seven of the ten fastest-growing internet populations are located in Africa, home to what is also the youngest population in the world, the future growth of the global e-commerce market depends upon unlocking the potential for e-commerce in Africa.

This post represents the views of the author(s) and not those of the Brexit blog, nor of the LSE. This blog post introduces is part of a series on digital trade that emanates from an extended and detailed simulation of the current WTO negotiations on e-commerce by LSE Masters students in the International Relations Department.