Following the recent Brexit vote, it appears that neither David Cameron nor Tory contenders for the top job like Theresa May are willing to trigger the notorious Article 50 ‘before the end of the year‘. This is ironic because we were repeatedly told by Brexiters that we need to ‘take back control’ of our country as soon as possible. Yet, as political instability seems to kick in, Brexit developments appear to resemble a ‘moving’ image of the ‘School of Athens’ – Raphael’s most famous fresco in Vatican City.

Look at the centre of the fresco: Conservative Eurosceptics Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, like modern versions of Plato and Aristotle, debate, with extraordinary slack, alternative strategies that will protect our economic and political interests outside the EU. But as Michael Gove suddenly decides to throw his hat in the UK leadership job, Boris Johnson moves out of the centre of the fresco to take up the less prominent role of philosopher Epicurus who became famous for attaining a happy life free of ataraxia (that is, peace and freedom from fear).

In the meantime, George Osborne, like a modern version of Pythagoras, frantically sketches on his notebook alternative trade models. Sketches of these models (such as the Norwegian, the Canadian, or even the Albanian model) will be Osborne’s legacy to the next Chancellor of the Exchequer as competing options to sort out the incoming recession and its long-lasting (?) consequences.

In any case, and with Article 50 still inactive, financial markets appear to doubt whether British policymakers really want to exit the EU. This might explain, at least partly, why the sterling currency has steadied a bit (since 23 June) and why initial losses in the FTSE index have been reversed. Nevertheless, the spectacular lack of planning and preparation from the Brexit camp will, sooner than later, take its toll on the UK economy.

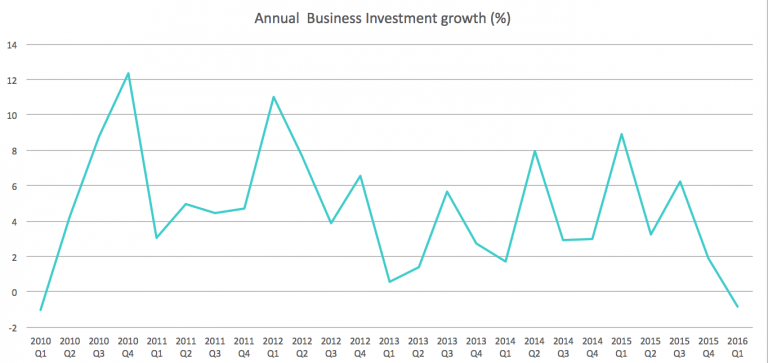

Indeed, it is not the day-to-day news coverage of big swings in the FTSE index that largely affect developments in the UK economy. Rather, one has to pay close attention to how business investment, the main driver of UK jobs and growth, evolves over time. The latest ONS figures (released on 30 June 2016) showed that in the first quarter of 2016, business investment fell by 0.8 per cent when compared with the same quarter a year ago. This is extremely worrying because the last time business investment decreased when compared with the same quarter a year ago was in the first quarter of 2010, when it fell by as much as 1.0 per cent (see figure below).

Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS). Seasonally adjusted figures

In other words, Brexit headwinds have already started making an impact on the economy – even before Brexiters won! It is this very worrying statistic, together with the release of UK GDP growth for the second quarter of 2016 (scheduled for release in late July 2016) that might force, sooner than later, the modern ‘School of Athens’ members to a pragmatic, yet cynic arrangement. This involves behaving like a modern version of Diogenes of Sinope, who (unsurprisingly) also makes an appearance in Raphael’s famous fresco. Or, in the words of Financial Times commentator Gideon Rachman, the very cynic scenario would involve ‘finding a deal that keeps the UK inside the EU’.

With none of ‘The School of Athens’ players in a hurry to trigger Article 50, this cynic arrangement, endorsed by a second referendum, remains a possibility. But even if we do trigger Article 50 and start the Brexit process, don’t even think that ‘it’s all over’. Indeed, as Phil Syrpis puts it ‘while the clock does start ticking once the Article 50 notification is made, it is at least possible that the process could be stopped at any stage – at the UK’s initiative’ if, for example, there is a change of government. Therefore, it appears that the referendum has in no way settled the issue of our relationship with the EU once and for all.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This article appeared originally at LSE British Politics and Policy.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Costas Milas is Professor of Finance at the University of Liverpool.

Costas Milas is Professor of Finance at the University of Liverpool.