Concentration and Power in the Food System: Who Controls What We Eat? Philip H. Howard. Bloomsbury. 2016.

‘Who controls what we eat?’

‘Who controls what we eat?’

Even before opening the book, this question, found on the cover of Concentration and Power in the Food System, is posed, inviting readers to contemplate just who exactly is involved in supplying our food.

The author, Philip H. Howard, uses this question as a platform to discuss the different stages of getting food from the farm/ranch to the dinner plate. In each chapter, Howard details a different part of the food system, whether that is exploring dominant firms and their roles in the system (including retail, distribution, farming/ranching and agricultural input production, such as seeds and fertilisers) or methods these firms employ to maintain and advance their power (manufacturing consumption, controlling prices, creating dependency and engaging with antitrust laws).

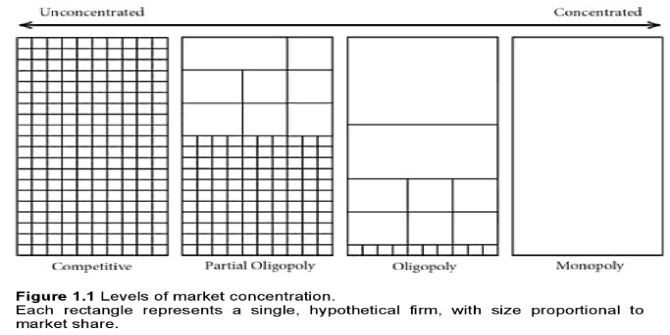

One particular aspect that Howard does very well is giving the reader the necessary theoretical background to understand the actions of major companies and their impact on the food system. Within the first chapter, he sets out the purpose of this book: ‘to illuminate which firms have become the most dominant, and more importantly, how they shape and reshape society in their efforts to increase their control’ (2). Following this, he wonderfully details the different types of market compositions, ranging from the most fragmented (competitive) to the least fragmented (monopoly). The figure used to highlight these different concentrations offers just one example of how graphics effectively display information within the book (3).

The second key concept, power, is also defined in the introduction as ‘the capacity of some persons to produce intended and foreseen effects on others’ (8-9). Howard uses this as the basis for arguing that capitalism is ‘a mode of power’ (11). Near the end of this opening chapter, he indicates that the food system has an hour-glass figure. At the top are the many farmers; at the bottom are those who eat the food; and in between are the few firms ‘that control how food is moved from producers to consumers’ (13).

The following chapter begins to unravel the food system, starting with retailers. As these companies are usually where people get their food from, it enables readers to personally connect with issues discussed in this book. Howard begins by explaining antitrust regulation and how its enforcement and interpretation have changed, particularly after the 1970s, when firms used different strategies, including ‘contributing financially to conservative politicians’ (18). Howard then focuses on supermarkets, convenience stores and fast food restaurants. In this chapter, like all chapters, he names and examines the top firms operating in the US with the highest market share.

In a similar fashion, within the third chapter, Howard looks at the distribution of food/beverages, meaning those firms responsible for moving products from suppliers to retailers. As is the case with retailers and other firms discussed in the ensuing chapters, power is established through buying out the competition. For example, Howard details how Sysco, a firm with 23.9 per cent of the market with $44 billion in sales in 2013, grew in power by ‘acquiring nearly 150 other companies or divisions since its founding’ (40-41).

The fourth chapter focuses on how consumption is engineered by different firms. The two overarching concepts introduced here are deskilling and spatial colonisation. Deskilling refers to how firms ‘reshape socio-cultural practices to increase purchases, moving us away from self-provisioning to become mere ‘‘consumers’’’ (50). For example, instead of boiling water for oatmeal, consumers can now purchase microwaveable versions (51). Spatial colonisation includes firms entering new markets and companies paying slotting fees for shelf space in the process of creating the appearance of diversity. Beer, soy milk and the bagged salad industries are all discussed in this chapter.

The fifth chapter highlights how firms manipulate prices to increase profit and sales. Howard focuses on the soybean, dairy and pork industries in the United States to illustrate how prices are decided. ‘As a small number of firms have increased their control […] they have gained the power to manipulate prices to their advantage, such as driving down the amounts they pay to suppliers and driving up the amounts they charge to buyers’ (71).

Farming and ranching are discussed in the next chapter with a particular emphasis on soybeans, milk, pork and leafy greens. Despite the decline of the number of farmers in the United States, agriculture is still one of the most fragmented parts of the food system through the continuation of smaller farms. Of critical importance in this chapter is how government subsidies are playing a role in supporting the growth of large-scale operations at the expense of mid-scale farms (89).

In Chapter Seven, agricultural inputs, particularly seed-chemicals and livestock genetics, are examined. Seeds used to be considered part of the global commons; however, over the past few decades, firms have been patenting their products so that farmers do not necessarily have the right to save patented hybrid seeds for future uses. Likewise, with animal genetics, many of the animal products for sale in the United States come from a select number of breeds. For example: ‘there are approximately 1,000 breeds of cattle worldwide, but just one breed, the Holstein [..] .makes up more than 85 percent of milking cows in the US’ (119).

In the next chapter Howard looks at the organic food chain and how certain companies are withstanding consolidation. He focuses on how definitions of ‘organic’ have been interpreted differently by the United States Department of Agriculture, large firms and smaller companies. He also details how certain large firms have acquired organic labels; however, they do not necessarily disclose information on the packaging. For those smaller firms who have chosen to remain independent, there is a sense of idealism towards what first motivated them to produce organic goods: ‘they have learned that acquisitions can have negative consequences for their non-economic goals’ (135).

In the last chapter, Howard tries to give a global perspective on the consolidation of food systems. He asks whether there will be a global monopoly, that is, whether ‘a few firms [will] end up controlling the entire world food system, from supermarket shelves to seeds’ (144). He concludes that while there will be the possibility of sectors being dominated by two firms, ‘few food industries will become global monopolies’ (144).

Overall, this book is an excellent introductory text to food systems. A notable aspect is the clarity of Howard’s argument. This is achieved by each chapter having a similar structure whereby firstly the issue is introduced; secondly, examples are given; and thirdly, attention is focused on what society is doing to tackle, improve or change the industry.

Another highlight of this book is the extensive reference list comprising 38 pages. It is very well researched and Howard uses information from a variety of sources including media reports, academic articles and international organisations. Everything from the language and quotes Howard uses to the diversity of examples discussed makes Concentration and Power in the Food System an intense yet enjoyable read. Overall, this short book is packed with so much information and different points of discussion that it not only leaves readers impassioned, but also hungry for more.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This post appeared originally at LSE Review of Books.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: 20110715-RD-LSC-0062 (US Department of Agriculture CC2.0)

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Kathleen Chiappetta has a Bachelor of Journalism Degree from Ryerson University in Toronto and a Master of Science Degree in Global Politics from the LSE. Over the years she has written and produced pieces on national and international issues such as agricultural and maritime trade, engineering education and Irish migration. She has worked for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in Geneva, the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Paris and the High Commission of Canada in the United Kingdom. She is currently working as a Domestic Trade Policy Officer for the Government of Alberta in Canada.

Kathleen Chiappetta has a Bachelor of Journalism Degree from Ryerson University in Toronto and a Master of Science Degree in Global Politics from the LSE. Over the years she has written and produced pieces on national and international issues such as agricultural and maritime trade, engineering education and Irish migration. She has worked for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in Geneva, the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Paris and the High Commission of Canada in the United Kingdom. She is currently working as a Domestic Trade Policy Officer for the Government of Alberta in Canada.