| This article appeared first on LSE's Latin America and Caribbean blog. Follow them on Twitter: @LSE_LACC |

The announcement in December 2014 that diplomatic relations would be re-established undoubtedly marked a turning point for Cuba. Over the rest of president Obama’s second term, a series of executive actions and bilateral agreements eased certain sanctions and strengthened cooperation in areas like environmental protection and security. Since these measures have benefited Cuba economically, their reversal should also prove detrimental. But the real picture is a little more complex.

The most important effect of rapprochement was a significant influx of international visitors. Although US sanctions continue to prohibit US tourism, the number of US visitors has boomed. Travel remains restricted to ‘purposeful’, licensed trips, but the once arduous licensing process now involves only a simple declaration, and the restoration of direct scheduled flights has helped to meet this new demand. Between 2014 and 2016 the number of US visitors reportedly trebled to 285,000. Although US visitors make up just one tenth of total visitors, the change in US policy has also prompted an unexpected surge in arrivals from other countries. These holidaymakers from Europe, Canada, and beyond are apparently rushing to reach Cuba before it is overwhelmed by a full opening-up to US tourists and business.

Figure 1: International arrivals and earnings 2007-16

Official figure. 2016 estimate. Source: Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información

As figure 1 shows (above), Cuba has been enjoying a tourist boom since 2014, with international visitors up by 16 per cent in 2015 and a further 13 per cent in 2016. Using official data for tourism earnings in 2015 and assuming that these flows rose in line with arrivals, this would have lifted total earnings to around US$3.4bn in 2016. The extra spending provided a particularly strong stimulus to the emerging private sector – private renters (casas particulares), restaurants (paladares) and taxis, particularly in Havana, where many prices have more than doubled and innovators have been rewarded. Private (formal and informal) providers of building and mechanical services have benefited similarly.

The rise in visitor numbers has also meant a surge in remittances, as established family links and new friendship ties have brought in gifts and stimulated private enterprise, particularly refurbishment of homes for rent. Remittance flows are difficult to measure – most still arrive in cash, making them indistinguishable from informal tourism earnings that are undeclared for tax purposes – but estimates indicate that they may have grown in line with US visitor numbers. This would suggest that they amount to approximately the same sum as the official figure for tourist earnings.

While government tax revenue received a boost from registered, tax-paying private enterprises, anecdotal evidence confirms that a large proportion of the additional economic activity has not been officially recorded. The main losers from any Trump policy reversal are therefore likely to be the new private entrepreneurs rather than the Cuban state.

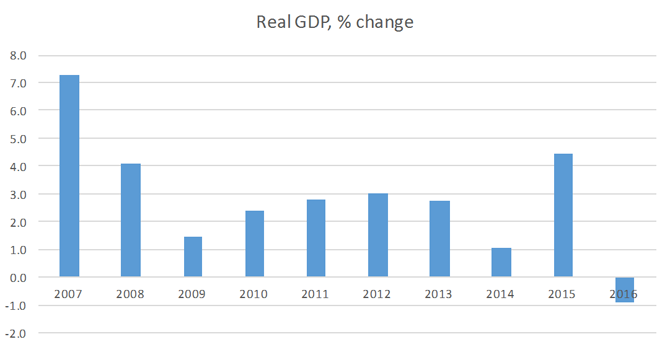

This is one reason why Cuban GDP contracted in 2016 (see Figure 2, below) despite the US measures and the related increase in visitors and remittances. Tourism and remittances, while important, do not dominate the Cuban economy. Tourist revenue accounts for only 15 per cent of export earnings and remittance flows for a similar amount. The overall performance of the Cuban economy since 2014 has been determined by other sectors, which have fared poorly for three reasons: US sanctions, most of which remain in place; a reduction in Venezuelan support; and Cuba’s efforts to improve its creditworthiness.

Figure 2: GDP change in Cuba 2007-16

Source: Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información

Despite the changes since 2014, Cuba’s goods exports and ability to attract foreign investment are still asphyxiated by US sanctions, most of which remain locked into US law. The scope for relaxing restrictions by executive order was limited, with only minor exemptions (such as for US agricultural exports). Proposals for comprehensive repeal were unable to gain majority support in Congress. Aside from blocking US-Cuban economic relations, this acts as a major deterrent to trade and investment between Cuba and other partners.

Venezuela’s economic difficulties, meanwhile, have badly hurt the Cuban economy over the past two years. In 2014 around half of Cuba’s export earnings came through the exchange of professional services (mainly medical) for Venezuelan oil, but this supply has declined just as tourism has surged. Although Cuba has begun to import oil from other suppliers, the earnings decline and economic disruption caused by reduced deliveries offset the foreign-exchange and fiscal benefits of the tourist boom.

The third cause of weak growth is the government’s determination to restore access to international finance by resolving long-standing disputes with creditors. The successful conclusion of an agreement with the Paris Club of official creditors in late 2015 led to bilateral settlements with its members in 2016. Because US law dictates that Cuban economic data should be used to better target sanctions, Cuba still regards such information as security sensitive, making data on capital-account transactions extremely sparse. But official statements suggest that restoring credibility with creditors has come at significant cost.

So, if the Trump administration were to reinstate restrictions on US visitors and reignite old hostilities, the Cuban economy would certainly suffer, but the macroeconomic effects would not be catastrophic. Reinstating restrictions on US travel would most acutely affect those who have enjoyed the greatest benefit – including the private restauranteurs, bed and breakfast owners, and taxi drivers of Havana – rather than the Cuban state. Moreover, the enthusiasm of US visitors for Cuba travel, once galvanized, will be difficult to reverse. It is unlikely that any presidential decree will entirely disrupt new networks of friendship and cooperation in many fields, from cultural and academic links to new business and investment relations involving US residents in Cuba’s emerging small businesses. What’s more, the negative impact of declining benefits from Venezuela has been largely absorbed and a resolution of Paris Club debts achieved, making the economy somewhat less vulnerable to a reversal of US rapprochement than it would have been a year ago.

Yet there is palpable concern in the Cuban government and amongst Havana’s entrepreneurs about the risks posed by the new US administration, particularly given the pro-sanctions posture of some senior appointees. The Cuban government has reiterated its willingness to continue discussions on the basis of “mutual respect”, but initial indications from the White House suggest that talks are likely to stall.

To protect against negative economic effects, the Cuban foreign ministry will intensify its already active efforts to build ties with other partners. Besides completing the Paris Club agreements, Cuba has recently signed a cooperation agreement with the European Union and made progress towards joining the Corporación Andina de Fomento (Latin America’s development bank), as well as further strengthening ties with Russia, China, and other partners on every continent. Domestically, Cuba’s economic reforms aim to increase openness to international trade and investment, and any attempt by the US to ‘isolate’ Cuba is instead likely to provoke wider international integration. Paradoxically, the short-term costs that such efforts might impose on the Cuban economy could be more than offset by the long-term benefits of a broader push towards new global connections.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post appeared originally in LSE’s Latin America and Caribbean blog.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Havana, by tpsdave, under a CC0 licence

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Emily Morris is an Associate Fellow of UCL Institute of the Americas. She has held research and teaching positions at various UK universities, as well as spending thirteen years at the Economist Intelligence Unit, where she specialised in Latin America.

Emily Morris is an Associate Fellow of UCL Institute of the Americas. She has held research and teaching positions at various UK universities, as well as spending thirteen years at the Economist Intelligence Unit, where she specialised in Latin America.

2 Comments