The increasing importance of digital platforms and data to our lives is perhaps the defining trend of the 21stcentury so far. Facebook, in particular, wants to be essential to you: you can connect with friends, shop in the marketplace, and read the headlines, all for the cost of nothing more than tens of thousands of data points about you that Facebook can then use to increase the value of its advertising space.

This shift towards providing huge companies with ever-more data about you is enormous, made possible by astonishing developments in technology that enable more data collection, storage, analysis, and generation than would have seemed possible just a few years ago. And it’s precisely the speed and magnitude of this change that make it important that we base concerns – and policy or regulatory responses – on as sound an understanding as we can.

At a recent LSE public lecture, Professor Bev Skeggs spoke about the potential for trends around data to lock in inequalities, citing evidence of the incredible scale of Facebook’s data collection, whether or not you’re logged in. If you heard the lecture, you might think it’s about to get much worse: several times during the talk Professor Skeggs mentioned a forthcoming EU Directive that would mean Facebook “will be able to actually access banking information and all banking is going to be completely deregulated and open to [non-]financial companies”.

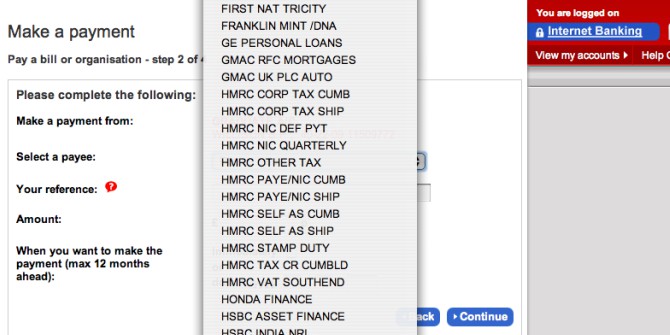

The Directive certainly exists: it has the catchy title of the Second Payment Services Directive, or PSD2. It’s an EU law that the UK is required to implement. But the alarming scenario of an unregulated banking space in which Facebook, having made itself indispensable to our social lives, will get unfettered access to our entire financial history needs quite a lot of caveats.

The Directive, which will be implemented through the Payment Services Regulations 2017 by the Treasury, sets out that any company operating a payment account (e.g. a current account) has to provide a way for third parties to access the information in that payment account – provided that the customer has consented. So an important first point is that Facebook won’t get automatic access to your bank data, nor do you have any obligation to give it that, either directly or via an app that ‘piggybacks’ on Facebook Messenger to offer a service (such as Cleo or Plum).

It’s also important to know that you can’t give that access to just anyone. Any provider of third-party services – in the jargon, Account Information Service Providers (e.g. budgeting services) and Payment Initiation Service Providers (e.g. saving services) – must be authorised by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), and your bank will have a responsibility to make sure any third party they allow to access the information is both FCA-authorised and has been permitted by you to access it. It will certainly not be ‘completely deregulated’.

It’s very likely that Facebook will launch its own service once PSD2 comes into force (as will, no doubt, Google, Paypal, Apple etc), and we will start to see technology and media companies increasingly entering financial services and competing with startups and established financial services providers.

This does raise a wide range of questions, including about data security, consumer rights in the event of a breach or fraudulent payment, and whether Google and Facebook will corner this market given their familiarity and power elsewhere. And none of this means that there aren’t important questions to be asked about our reliance on huge technology companies and the regulation and enforcement of what they are able to do with information about us, or how that will affect our society – from fake news, to privacy, to inequality.

But these are complex, difficult, new, and interconnected questions – which is why it’s especially important that discussions of the problems and potential solutions are based on sound understanding of what’s actually happening.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This article was first published by LSE Media Policy Project.

- The post gives the views of the author, not the position of LSE Business Review, LSE Media Policy Project or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: HSBC internet banking (cropped), by Simon Willison, under a CC-BY-NC-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Jamie Thunder is senior policy adviser for the consumers’ association Which?

Jamie Thunder is senior policy adviser for the consumers’ association Which?