Work-life balance has been a hot topic for organisations and HR practitioners for many years – linked to range of individual and organisational benefits. The shift from the terms ‘family-friendly’ and ‘work-family balance’ to the more inclusive ‘work-life balance’ around 2000 indicated a shift in rhetoric that all employees, regardless of domestic situation, deserved a suitable balance between the demands of work and home in order to be happy, healthy and productive. But do all employees actually feel that their organisation’s work-life balance policies and provisions cater for them? And what happens when they don’t? Our recent publication on work-life balance for managers and professionals who live alone and don’t have children explores these issues.

In the article, we explore a paradox that was evident in our data from 36 in-depth interviews with managers and professionals aged 24-44 from a range of sectors and occupations in the UK. Whilst most of the participants suggested that they had considerable personal work-life balance challenges, and also that their organisations’ work-life balance policies did not cater for these needs, there was little evidence of perceived unfairness, and associated ‘family-friendly backlash’ – whereby individuals react to perceived unfairness by voicing complaints and/or engaging in counterproductive work behaviour. Rather, individuals largely accepted the seemingly ‘unfair’ allocation of work-life balance support – rationalising the policy provisions due to both national context (legislative provisions) and the balance of other organisational ‘benefits’.

So what work-life balance challenges were reported by these individuals? We found four distinct themes:

- Individuals who lived alone without children felt that their organisations and colleagues assumed they could work longer hours, as they did not have as many demands on their time outside of work as parents do. On the contrary, they spoke of specific types of time demand – often as a result of their solo‐living status. These included having sole responsibility for the household and the need to invest time and energy in friendships and developing intimate relationships (which was hard when long hours and mobility demands were common).

- Concerns about the perceived legitimacy of their WLB needs

- Lack of support (financial and emotional) in the non-work domain

- Heightened work-based vulnerability

More detail on these challenges is provided in another article.

When asked about the work-life balance policies, provisions, and cultures in their organisations, participants reported either a prioritisation of the needs of working parents, or limited personal awareness/understanding of the specifics of policies – but with an assumption of the prioritisation of family needs: “I think the work–life stuff is mainly designed for people with kids. That’s what it’s targeted around, it’s not really relevant [to me]”. This is not surprising, as research has found that the ‘life’ element of organisational provisions is often very narrowly defined.

Three reactions were identified in relation to the discrepancy between policy provision and personal need. Firstly, several participants did not pick up on the discrepancy between policy provisions and their own needs, and so did not perceive unfair treatment – even when they had explicitly cited examples of differential treatment, around for example requests for flexible working.

Secondly, many participants rationalised differential treatment. For some, the view was that whilst they might have personal work-life balance challenges, working parents surely had it harder. For others, it was that their own lack of work-life balance was offset by other rewards in the organisation, such as career development opportunities and progression, which were less likely to be given to working parents in receipt of flexible working.

Finally, for a small number, a sense of unfairness was articulated in the interview, but this was not something they had voiced in their organisations. Their silence was often attributed to concerns about the perceived legitimacy of their non-work needs, and criticisms tempered by reference to largely family-focused legislative provisions. They did not consider their organisation to be acting unfairly – it was just how things were nationally.

At this point, you may be thinking ‘so what?’ If many of these employees don’t perceive any unfairness, and none engage in backlash behaviour, then why should organisations be concerned by these findings? We argue there is a danger in such thinking. Organisations often invest considerably in their work-life balance provisions due to the recognised benefits to both employees and the company. If the provisions are missing the needs of large – and indeed growing (research indicates an ongoing increase in solo-living within the working age population) – sections of the workforce, then these benefits will not be maximised. Where individuals do feel a sense of unfairness, but remain silent, there might be considerable consequences for employee engagement. Furthermore, there are implications for us-and-them cultures between those that use and those that do not use work-life balance provisions, which research has shown can lead to those that do use policies feeling this negatively affects their career prospects.

We urge HR practitioners and senior managers to examine existing work-life balance policies and provisions to scrutinise the extent to which they cater for those with work-life balance requirements beyond care responsibilities and how widely work-life balance issues are framed. Greater communication of changes to policies in line with the 2014 extension of the right to request flexible working would be one step in this direction. In encouraging wider understanding, legitimacy and use of work-life balance and flexible working arrangements, such provisions might become more normalised within the culture of organisations.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the author’s The perceived fairness of work–life balance policies: A UK case study of solo‐living managers and professionals without children, co-authored with Jennifer Tomlinson and Jean Gardiner, Human Resources Management Journal, April 2018.

- This post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

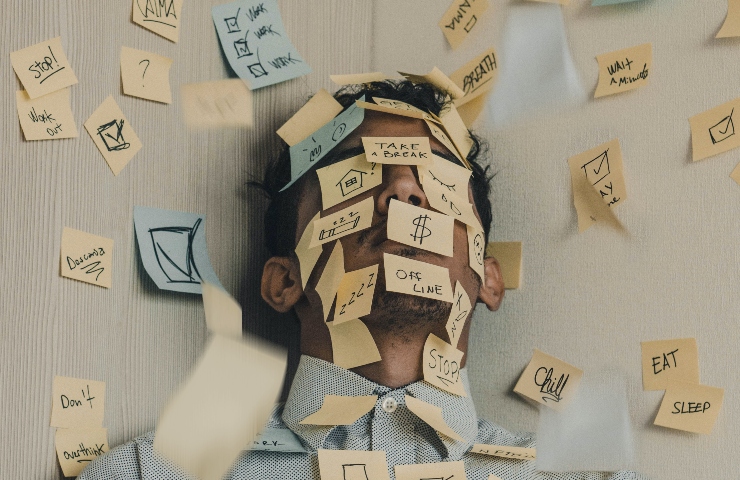

- Featured image credit: Photo by epicantus, under a CC0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Krystal Wilkinson is a senior lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University (department of people and performance), and a member of the University Centre for Research and Knowledge Exchange in Decent Work and Productivity. Her PhD from Leeds University (2015) focused on work-life balance for managers and professionals who live alone and don’t have children, and her most recent project focuses on the intersection of fertility (including assisted fertility treatment) and work.

Krystal Wilkinson is a senior lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University (department of people and performance), and a member of the University Centre for Research and Knowledge Exchange in Decent Work and Productivity. Her PhD from Leeds University (2015) focused on work-life balance for managers and professionals who live alone and don’t have children, and her most recent project focuses on the intersection of fertility (including assisted fertility treatment) and work.

Very interesting and nuanced blog on a topic that is little talked about, thank you. I believe one of the reasons why single childless people do not complain openly about their situation, is that this situation is supposed to be transitory. Most people do not decide to be single and childless, they endure it for a more or less long period of time. On the other hand, voluntary long term singles would be badly perceived by society, They are not even supposed to exist.

In some ways, work-life balance is even more essential for single, childless people. The worker with a family goes home to a family. The single, childless worker who spends long hours at work is dangerously socially isolated. In addition, a family can juggle; the 16-year-old can walk the dog, for example. If the single, childless worker has no one to walk the dog, can’t be two places at one time, and therefore doesn’t get a dog, that’s more social isolation.

A big problem that doesn’t get the attention it deserves, especially how it impacts men. Most companies have come to expect 24/7/365 dedication to duty from employees.