Ethiopia’s liberalisation offensive, opening up the state controlled Ethio telecom and Ethiopian Airlines to private investors, has taken many by surprise. Caught between a watershed political transition and a foreign currency crunch, opinion remains divided as to whether the move primarily signals a policy shift to relatively fast-pedalled liberalisation under the new administration, or is intended to serve as a way out of the stranglehold of foreign currency scarcity.

It is easy to see where hopes that it will play the latter role are hinging on.

A consortium led by Italian firm Enel Green Power (EGP) is expected to invest about $120 million in the construction of a 100 Mw solar plant in Metehara, Central Ethiopia, having been awarded the contract in October 2017. Due for completion in 2019, the project is expected to sell power to the state-owned electricity producer, Ethiopian Electric Power, within the framework of a two-decade long Power Purchase Agreement. Understandably, such private sector participation is viewed as a pivotal amplification channel for the inflow of hard currency into the economy.

Ethiopia’s foreign currency woes, however, run deeper than the narrow optic of liberalisation would suggest. In October 2017 the National Bank of Ethiopia (the country’s central bank) not only hiked interest rates, but, more importantly, devalued the Birr by 15.5 per cent to exchange at 27.3 units to the dollar. This shock policy adjustment came at a time when, by and large, the monetary environment was becoming a lot more accommodative of dovish signals in sub-Saharan Africa, with central banks beginning to unwind the tightening cycle that had prevailed for the better part of 2014 – 2016. If there was a canary in the coalmine with regard to the headwinds the economy was confronting, run-away inflation and a foreign currency crunch, that was it.

$6.3 in servicing import obligations for every $1.0 in export revenue

Between 2010 and 2016, Ethiopia grew its exports by a paltry 1.9 per cent (compound annual growth rate) to $2.8 billion. In the same period, imports surged by 11.4 per cent to $16.4 billion, according to the International Trade Centre. In essence, whereas the economy in 2010 needed $3.7 to service import demands for every $1.0 it generated in export proceeds, by 2016 this had risen to $6.3 for every $1.0 in export earnings.

To put this into perspective, peer economies in the larger Eastern Africa region paint a different picture – in 2010 Kenya and Tanzania needed $2.3 and $2.0, respectively, to meet import obligations for every $1.0 they made in export earnings. By 2016, the two countries needed $2.9 and $1.7, respectively, for the same purpose.

This widening trade imbalance begins to put into perspective the stranglehold of the foreign currency shortage that Ethiopia finds itself in today – an environment of almost stunted growth in export earning inflows against sustained increase in import servicing outflows.

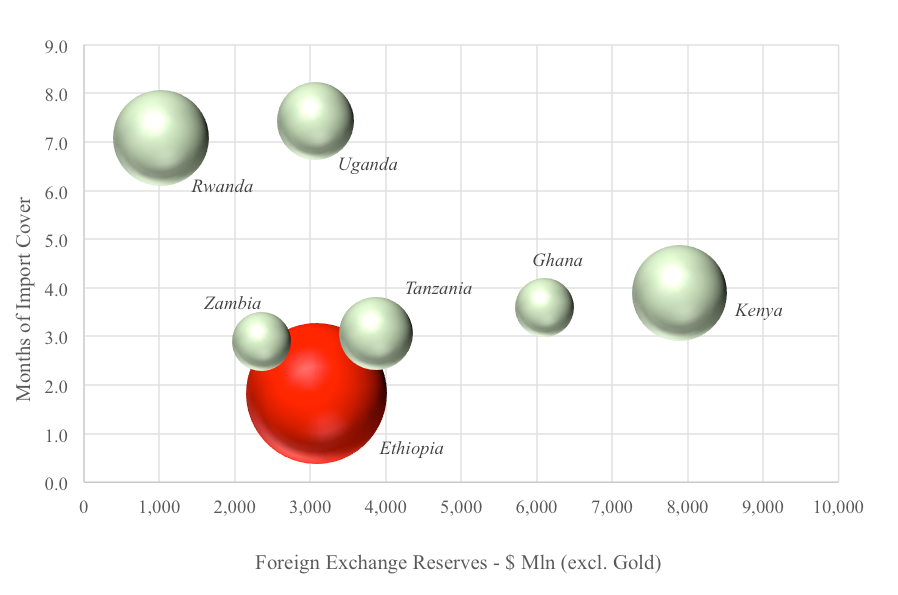

The chart below plots the foreign exchange reserves, months of import cover and number of dollars needed to service import obligations for every dollar earned in export revenue (size of the bubble). It shows that by 2016, Ethiopia’s foreign exchange reserves amounted to only 1.8 months of import cover. Important to note is that the International Monetary Fund’s Reserve Adequacy Template prescribes relatively higher reserves (5.0 – 6.8 months of import cover) for countries with an exchange rate system similar to Ethiopia’s i.e. a considerably managed float system that sees regular intervention by the central bank to smoothen out volatility. As such, 1.8 months of cover suggests a particularly thin buffer against shocks for the economy, a fact that has been brought to bear given the nosedive in the price of coffee (which accounts for 17 per cent of export earnings).

Figure 1. Foreign exchange reserves and months of import cover, 2016

Source: Africa Export-Import Bank. Note: Size of bubble denotes the number of dollars required to service import obligations for every dollar in export earnings.

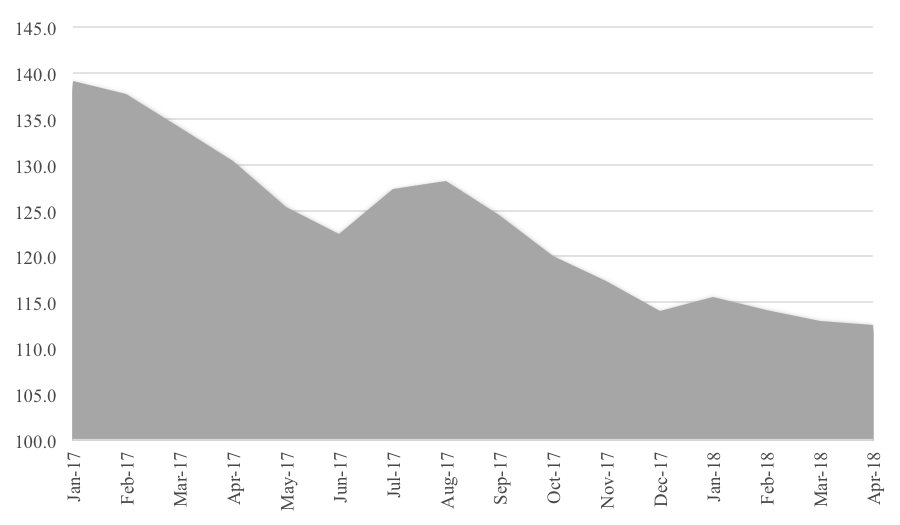

Figure 2. International price of coffee (US cents per lb)

Source: International Coffee Organization

The export market concentration bogeyman

The Hirschman-Herfindahl Index (HHI) is a tool used to assess the concentration of a country’s trade (import and export) in terms of product and markets. The index ranges from 0 to 1 referring to least and most concentration, respectively. One of the legacies of the 2014 – 2016 commodity price downturn has been to create, in sub-Saharan Africa, an overwhelming focus on the need to de-risk economies through diversification of export products. Unfortunately, little focus has been channeled towards diversifying export markets as a balancing wheel for strong and sustainable growth momentum.

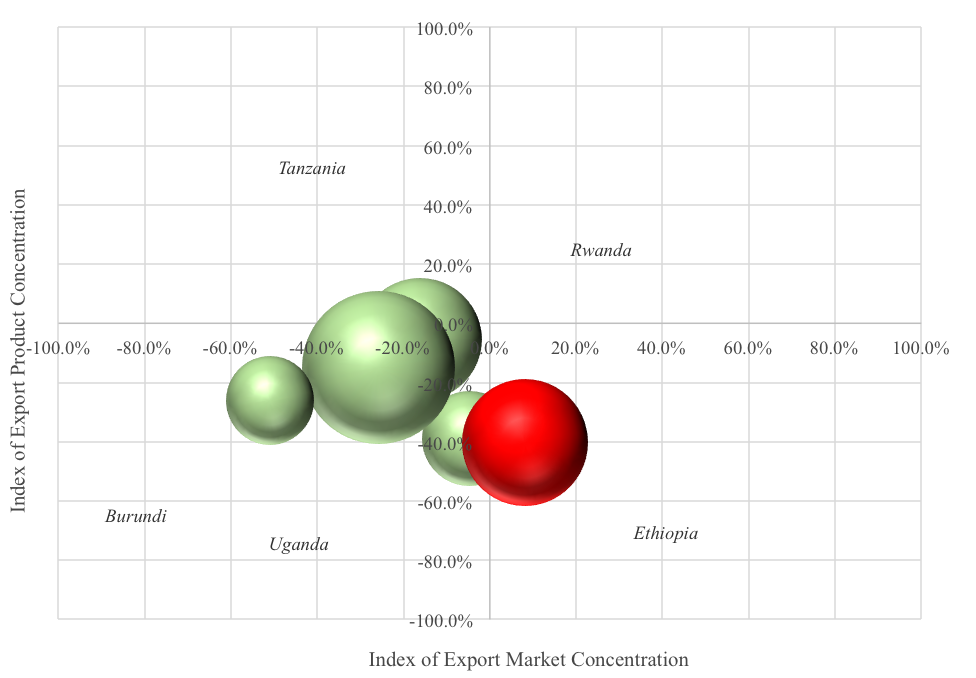

In Ethiopia’s case, growing export market concentration has presented a risk. The graph below shows the change in HHI, both product and market concentration, for Ethiopia and peer economies between 2000 and 2014. What can be observed is that whereas Ethiopia, like most peers, has diversified export products, it is the only country that has experienced growing concentration in its export markets. This growing concentration is attributable to deepening Sino-Ethiopian ties, which have seen China grow to account for 13.4% per cent of Ethiopia’s exports in 2016 compared to 1.1 per cent in 2001, according to the International Trade Centre.

This concentration has left Ethiopia vulnerable to China’s waning appetite for imports, which declined from $1,949.9 billion in 2013 to $1,587.9 billion in 2016. At the same time, loans extended by China to Africa declined from a peak of $16,669.3 million in 2013 to $11,764.3 million in 2015 with Ethiopia, being the second largest recipient of loans after Angola, bearing the brunt of the tightened purse strings (data from the China-Africa Research Initiative).

Figure 3. Export product and market concentration

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution database

Where does Ethiopia go from here?

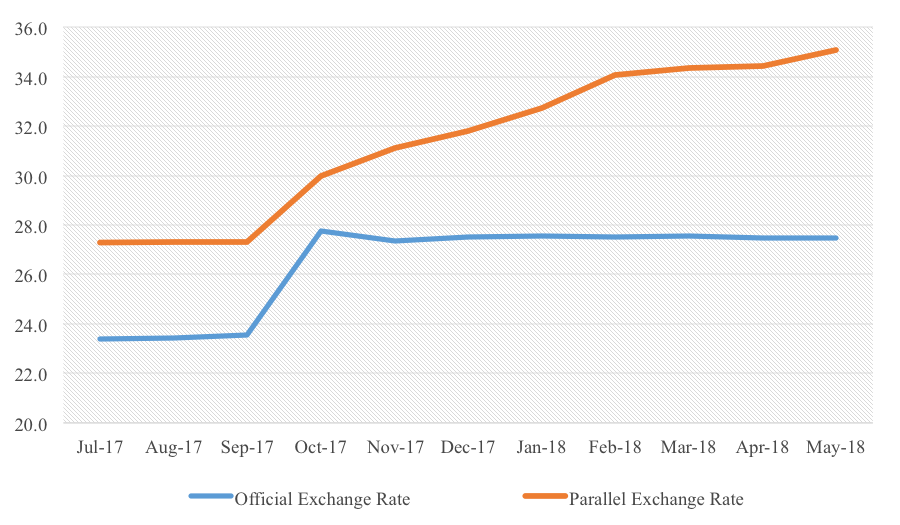

Ethiopia finds itself in a bind. On one hand, anecdotal evidence suggests that the gap between the official and parallel exchange rate continues to widen, exchanging at 35.0 – 35.5 units to the dollar as of 9 June, 2018. With this parallel market premium in mind, it is likely that a second, albeit smaller, devaluation of the Birr is within the National Bank of Ethiopia’s tool box for the short to medium-term horizon.

On the other hand, the devaluation-related inflation pass through effects, at a time of double-digit inflation, takes away from the allure of such a stance. More consequentially, this moment of distress could present a turning point at which Ethiopia begins to consider a future in which the country decouples itself from a considerably managed exchange rate regime in favour of a more flexible system. Perhaps a more flexible regime will enhance the capacity for price discovery and allow for early detection of a build-up of external imbalance vulnerabilities should similar pressures recur in the future.

Figure 4. Ethiopian birr to the US$ exchange rate

Source: Bloomberg, StratLink Africa Ltd

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo by Rjruiziii, under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence, via Wikimedia Commons

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Julians Amboko is a Senior Research Analyst with StratLink Africa Ltd, a Nairobi-based financial advisory firm focusing on emerging and frontier markets. He covers macroeconomic research and analysis for Sub-Saharan Africa, including markets such as Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Angola. He tweets at @AmbokoJH

Julians Amboko is a Senior Research Analyst with StratLink Africa Ltd, a Nairobi-based financial advisory firm focusing on emerging and frontier markets. He covers macroeconomic research and analysis for Sub-Saharan Africa, including markets such as Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Angola. He tweets at @AmbokoJH