Currency unions are an important institutional arrangement to facilitate international trade and reduce trade costs. In the period since World War II, a total of 123 countries have been involved in a currency union at some point. By the year 2015, 83 countries continued to do so. In addition, various countries are considering to form new currency unions or to join existing ones. For example, the East African Community is thinking about setting up a common currency. Also, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden are supposed to join the euro at some point.

The traditional currency union effect on trade: one size fits all

By how much do currency unions facilitate international trade? To evaluate the trade effect of currency unions, researchers typically rely on a standard gravity equation framework, and insert a simple currency union dummy variable as a right-hand side regressor (e.g., Rose, 2000). This yields a single coefficient to assess the trade effect of currency unions. By construction this effect is homogeneous across all currency union country pairs in the sample. Researchers have often found large effects, and by construction these equally apply to all bilateral pairs in the sample that are in a currency union. But the results are not always clear-cut since they can vary a lot across samples (see Glick and Rose, 2015, 2016).

A new approach: Heterogeneous currency union effects

In new research (Chen and Novy, 2018), we challenge the view that currency unions have a homogeneous “one-size-fits-all” effect on bilateral trade flows. We argue theoretically, and demonstrate empirically, that the trade effect of currency unions is heterogeneous both across and within country pairs. As our theoretical framework, we introduce heterogeneous currency union effects by taking guidance from a translog gravity equation that predicts variable trade cost elasticities (Novy, 2013). This means that a currency union (through lowering trade costs) will not have the same effect on all bilateral trading relationships between member countries.

In our framework, “thin” bilateral trade relationships (characterised by small import shares) are more sensitive to trade cost changes in comparison to “thick” or “established” trade relationships (characterised by large import shares). As an example, think of Germany importing from Malta as a thin relationship. Malta is not a large economy, and therefore its share in German imports is small. This is the type of bilateral relationship that benefits the most from joining a currency union in terms of increased trade. In contrast, think of Germany importing from France. This is a thick relationship with a large share in German imports. This type of relationship is not very sensitive to a reduction in trade costs induced by their currency union. Bilateral trade between France and Germany therefore does not move much.

The intuition is that small import shares are high up on the demand curve where sales are very sensitive to trade cost changes. Large import shares are further down on the demand curve where sales are more buffered. As a result, smaller import shares have a stronger trade cost elasticity in absolute magnitude.

Heterogeneous currency union effects in the data

We use a very large, comprehensive data set of aggregate annual bilateral trade flows, covering the vast majority of global trade after World War II. It consists of trade flows for 199 countries between 1949 and 2013.

We first estimate a standard gravity regression without heterogeneous effects. We find that sharing a common currency is associated with roughly 40 per cent more trade on average. But once we allow for variable effects across country pairs, we find a great deal of heterogeneity. For instance, at the 90th percentile of import shares (these are the “thick” relationships), we find that the trade effect of sharing the same currency is relatively modest at 30 per cent. In contrast, at the 10th percentile (these are the “thin” relationships), we find a substantially stronger effect of 94 per cent.

Examples of country pairs with small import shares associated with large currency union effects are Denmark importing from Greenland (115 per cent), and Mali from the Central African Republic (98 per cent). In contrast, country pairs with large import shares that do not increase trade at all by joining a currency union include Belgium-Luxembourg importing from the Netherlands or Germany.

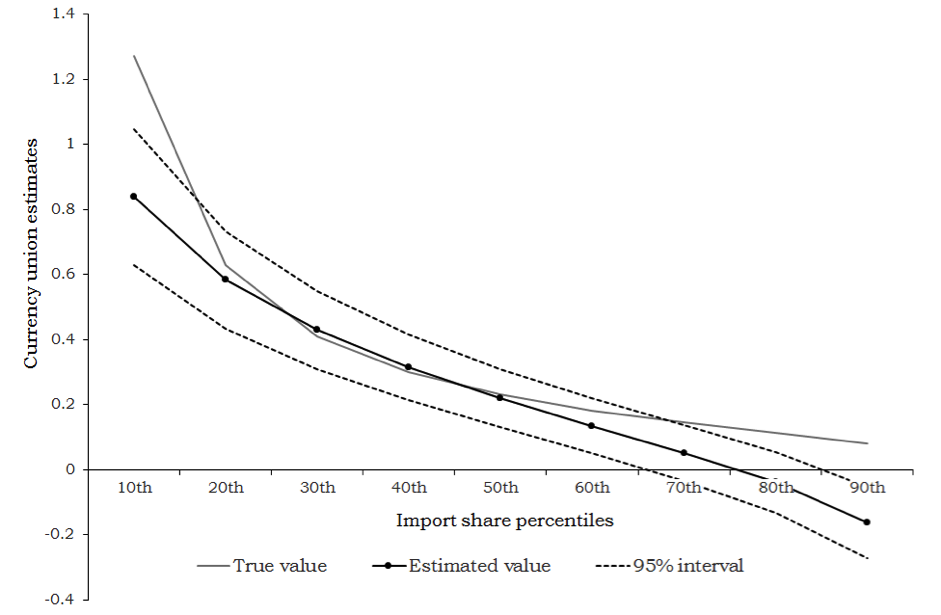

Figure 1 illustrates this basic result. Small import shares (those at low percentiles) are associated with large currency union effects, and vice versa.

Figure 1. Estimated currency union effects plotted against the size of import shares

Notes: Currency union effects on trade are strong for small import shares and weak for large import shares. Note that the numbers in this figure are based on a particular simulation and therefore may differ quantitatively from the numbers mentioned in the text. But qualitatively, the relationship is the same.

Asymmetries within country pairs

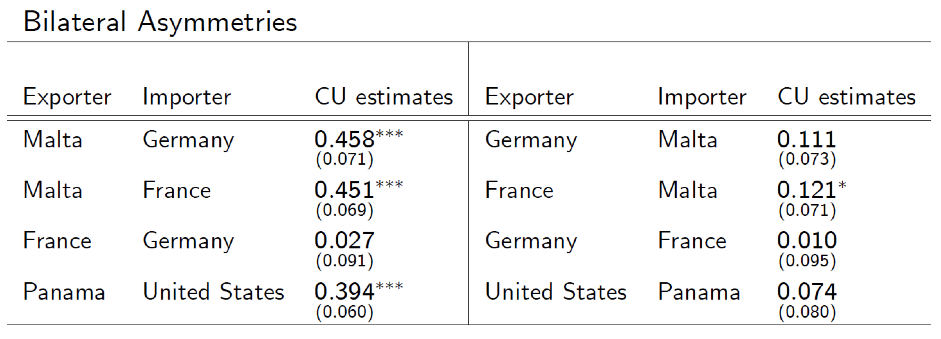

We also find that the trade effect of currency unions is heterogeneous within country pairs and therefore asymmetric by direction of trade. Table 1 illustrates a few of these results.

Table 1. Asymmetries of estimated currency union effects within country pairs

Notes: Currency union (CU) effects within country pairs differ by the direction of trade. The table shows point estimates for currency union effects with standard errors reported in parentheses (asterisks denote significance). The estimates have to be exponentiated to obtain the trade effects. For example, for trade from Malta to Germany, we find a trade effect of 58 per cent, which is computed as exp(0.458)-1.]

How about the euro?

The euro’s 20th anniversary is coming up. Given the enormous academic and policy interest in the European single currency, we also focus more specifically on the trade effect of the euro.

We also find that the euro effect is heterogeneous across country pairs. It is insignificant at the 90th percentile of import shares. But it becomes significant and equal to 36 per cent at the 10th percentile. Examples of country pairs with small import shares associated with large euro effects are Ireland importing from Cyprus (31 per cent), Finland from Malta (30 per cent), and Austria from Estonia (25 per cent). In contrast, country pairs with large import shares not generating any additional trade from the euro include Belgium-Luxembourg importing from the Netherlands or Germany.

Policy implications

Our results help to evaluate the potential changes in trade flows that countries can expect when joining a currency union. For instance, suppose Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden were to join the euro in the next few years. As these countries are relatively small compared to some existing members of the eurozone, such as France and Germany, they have relatively large import shares. Our results suggest that these import shares will grow modestly. However, trade shares in the opposite direction are smaller and can therefore be expected to grow faster.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post was published originally at VoxEU. It is based on the authors’ paper Currency Unions, Trade, and Heterogeneity, LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) discussion paper 1550. Also available as CEPR discussion paper 12954.

- The post gives the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo by hectorgalarza, under a CC0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Natalie Chen is associate professor of economics at the University of Warwick and holds a PhD in economics from the Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium. After completing her PhD she spent 2 years as a research fellow at London Business School in the economics subject area, and is a CEPR research fellow. She is mainly interested in applied issues related to international economics, covering both international trade and international macroeconomics, and is also interested in European Union market integration.

Natalie Chen is associate professor of economics at the University of Warwick and holds a PhD in economics from the Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium. After completing her PhD she spent 2 years as a research fellow at London Business School in the economics subject area, and is a CEPR research fellow. She is mainly interested in applied issues related to international economics, covering both international trade and international macroeconomics, and is also interested in European Union market integration.

Dennis Novy is associate professor of economics at the University of Warwick, a research fellow at the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and an associate at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). He works in the fields of international trade, international economics and macroeconomics. Dennis was appointed to the UK Council of Economic Advisers by the Chancellor of the Exchequer in 2018. He was the specialist adviser to the House of Lords on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) in 2013/14. Dennis has been a recent visitor at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and the University of California, Davis. He received a PhD from the University of Cambridge.

Dennis Novy is associate professor of economics at the University of Warwick, a research fellow at the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and an associate at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). He works in the fields of international trade, international economics and macroeconomics. Dennis was appointed to the UK Council of Economic Advisers by the Chancellor of the Exchequer in 2018. He was the specialist adviser to the House of Lords on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) in 2013/14. Dennis has been a recent visitor at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and the University of California, Davis. He received a PhD from the University of Cambridge.