In a 2010 speech, then-Prime Minister David Cameron questioned whether the United Kingdom’s dependence on the success of just a few prosperous places was economically wise. “Today our economy is heavily reliant on just a few industries and a few regions,” he said, adding: “An economy with such a narrow foundation for growth is fundamentally unstable and wasteful – because we are not making use of the talent out there in all parts of our United Kingdom.”

Without a doubt, Cameron’s comment was prescient in many ways, but it is now clear he was not prescient enough about his insight’s full implications: that the forces that have made the UK economically unbalanced have also left it politically vulnerable.

Cameron, in this respect, did not anticipate that the regional economic divides he saw in 2010 would in 2016 contribute to the political backlash of Brexit, which expressed in shocking terms the ongoing clash between two very different sets of places: one globalist, pro-European Union, pro-immigrant, and progressive and the other inward-looking, anti-EU, anti-immigrant, and nostalgic.

Nor did Cameron see that the UK was anything but an outlier. In fact, nearly all Western democracies — ranging from the UK to Hungary to Poland and the United States — are in the grip of the same dynamics of economic and political divergence. As we discuss in a new report released by the Brookings Institution in Washington D.C., virtually all of the advanced Anglo and European democracies are confronting specific and powerful forces of economic change that are decoupling urban and non-metropolitan areas, pitting prosperous “superstar” cities against stagnant or declining “places left behind.”

Trade is part of the story. But even more important, the digital economy that thrives on density and agglomeration is almost unavoidably exacerbating the divides within nations, by inordinately rewarding higher-skilled people and places while leaving those without such skills on the outskirts of prosperity.

Throughout the EU, the split is evident between diverse, economically dynamic metropolitan areas and the hinterland of small towns and rural areas. In many countries, the decline of industrial-era manufacturing and the rise of the information and service economy has deprived non-metropolitan areas of their economic rationale. Coupled with widening cultural differences and rising anxiety about refugee flows, this great transformation has fuelled the rise of populist parties and movements, several of which have come to dominate their countries. The political consequences of these geographical divides are stark. Budapest voted against Viktor Orbán, Warsaw against Law and Justice, yet populist parties rule Hungary and Poland.

And now, as we show, a similar set of dynamics is playing out in the U.S.

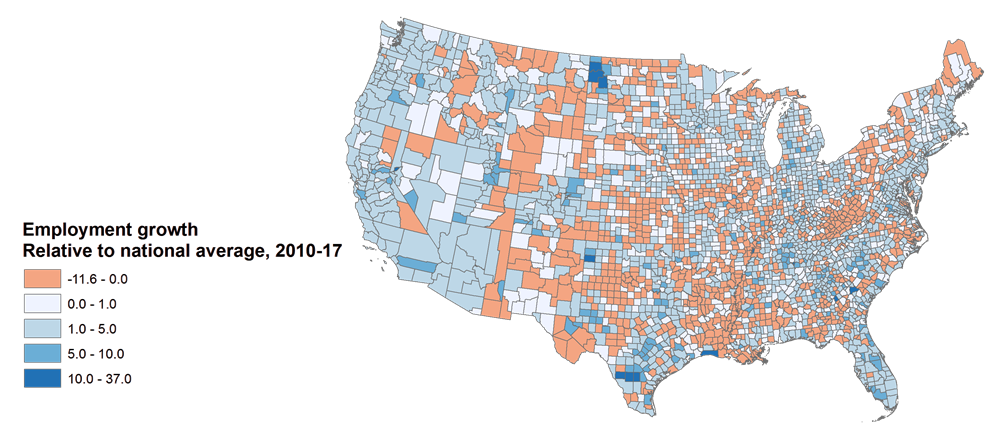

Figure 1. Employment growth relative to national average, 2010-17 (US)

In the U.S., the 2016 presidential election revealed an extremely stark divide between thriving metropolitan regions and places that had been left behind in a changing economy. Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party dominated the former, Donald Trump and the Republicans the latter. The recent midterm election saw this divide deepen, triggering predictions of a realignment of American politics along the axes of geography and culture.

The upshot: The populist politics produced by economic change, and the polarisation of people and places that results, constitute a severe negative externality few economists anticipated but can no longer afford to ignore. Absent intervention, we believe, the disparities between places will only intensify in the digital era to the detriment of the West’s economy and democracy.

So what is the way forward? In our new paper, we assert first that something must be done, that inaction is no longer acceptable. As to what such action might look like, we propose a route that moves between the familiar, often-opposed watchwords of “people-based” and “place-based” policy to embrace what the LSE scholars Simona Iammarino, Andrés Rodríguez-Pose and their colleague Michael Storper call “place-sensitive distributed development.”

What might this look like? Right off, we would suggest that it doesn’t look an awful lot like the EU’s territorial cohesion effort with its massive, top-down investments in physical infrastructure. While the initiative merits praise for its early awareness of the perils of regional inequality, its system of fiscal transfers has neither succeeded universally in regenerating regions nor fended off political challenges.

Rather, we would join Iammarino, Rodríguez-Pose, and Storper in suggesting that what is needed are strategies that respect the dynamism and efficiency of the agglomeration economy but that seek to extend that dynamism to more regions by helping them obtain greater access to the assets, conditions, and growth drivers needed to propel catch-up among select lagging places. As the LSE trio writes, “Economic development policy should be both sensitive to the need for agglomeration and the need for it to occur in as many places as possible.”

Along these lines, we think it’s now critical that national governments attend aggressively to the needs of drifting places to develop skilled 21st-century workforces, secure the capital needed to start and grow businesses, and achieve high-quality broadband. In a digital economy these are now essentials.

Beyond helping places secure the basics needed to enable convergence instead of divergence, we also believe it will be essential to develop strategies for more directly instigating new growth in places left behind. While it may be inefficient to “save” every left-behind small city or rural hamlet, place-sensitive policies can target a few promising mid-size communities adjacent to other lagging towns and rural areas. Along these lines, we are working in partnership with the innovation expert Rob Atkinson of the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation to develop a plan by which the U.S. federal government would designate through competitions 10 or so “growth poles:” medium-sized metros with genuine advanced-sector growth potential. These cities would gain access to a suite of research, tax, infrastructure, and economic development supports in exchange for strong strategic planning and governance reforms. In that fashion, their own gains would bring opportunity closer to more people and places. Likewise, we think that nations should provide financial support for individuals who want to make either long-distance or medium-distance moves to places that promise greater economic opportunity. More broadly, we would suggest that given the difficulty of the challenge at hand a new round of ambitious experimentation is essential.

Ultimately, we think the developments of recent years — both economic and political — now preclude inaction. After decades of drift, new and darkening realities have made it imperative that nations all across the West confront the cultural and economic cleavages separating their urban and small-town realms and seek to work out real answers.

And the challenge is stark. If the democracies don’t act, the populist insurgents will.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ report Countering the geography of discontent: Strategies for left-behind places, Brookings Institution, 2018.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of the institutions they represent, LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo by Mat Fascione, under a CC-BY-SA-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Clara Hendrickson is a research analyst at the governance studies programme at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC.

Clara Hendrickson is a research analyst at the governance studies programme at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC.

Mark Muro is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program and leads its Managing Disruption activities. His work focuses on the advanced technology economy, regional ecosystems, and city variation.

Mark Muro is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program and leads its Managing Disruption activities. His work focuses on the advanced technology economy, regional ecosystems, and city variation.

William Galston holds the Ezra K. Zilka chair in governance studies at Brookings. Prior to January 2006 he was the Saul Stern professor and acting dean at the School of Public Policy, University of Maryland, director of the Institute for Philosophy and Public Policy, founding director of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), and executive director of the National Commission on Civic Renewal.

William Galston holds the Ezra K. Zilka chair in governance studies at Brookings. Prior to January 2006 he was the Saul Stern professor and acting dean at the School of Public Policy, University of Maryland, director of the Institute for Philosophy and Public Policy, founding director of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), and executive director of the National Commission on Civic Renewal.