In the past decade, mobile payment systems (MPS) have rapidly emerged in many developing economies, addressing several well-known gaps in the provision of financial services. MPS, also known as mobile money, has allowed consumers who are often unbanked or underbanked, to transact and to store money more efficiently, thereby reducing the costs of engaging in undertaking all transactions, including purchasing and selling goods and paying labour.

Unlike traditional money that only banks provide, the digitalisation of money has allowed new entrants such as telecom groups and third-party providers to offer mobile money services to their clients. Notably, deliberate national and international structures of banking regulation have always aimed at preventing fraud and debasement have always governed the provision of money for economic exchange. In this regard, mobile money is no exception; however, now the regulatory and competition issues intersect banking and telecom regulations, which show wide variation at the national level.

Key question: how should mobile money be regulated?

The question of how to regulate mobile money has seldom been tackled by scholars (but see Porteous, 2006; Klein and Mayer, 2011). Most of the work advocates an “enabling regulation”, in the sense that the regulator should allow telecom to provide mobile money services. In reality, we see a large heterogeneity of experiences and different regulation models.

This brief gives an overview of the regulation landscape, introduces the key points of the mobile money regulation debate and describes regulation trajectories. This brief is informed by our broader research programme focused on mobile money in 90 countries and the complementary in-depth comparative research on regulation of mobile money (Pelletier, Khavul, and Estrin, 2019, 2019a).

Context: the spread of mobile money around the globe

Our research suggests that MPS develops especially in countries with low levels of development and with a relatively large population ((Pelletier, Khavul, and Estrin 2019). Its spread is facilitated by high levels of mobile phone penetration, limited prior access to formal banking services, and significant flows of money transfers such as workers’ remittances. These observations also motivate questions about the role of regulation in shaping the spread of mobile money. In the next section, we examine the different approaches to regulation and the debate around them.

Competing approaches to mobile money regulation

The regulation debate has centred on the following issues: the type of licensing needed to offer mobile money services; whether telecom operators can carry out such activities; Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) requirements; the regulation of the agent network; interoperability between providers; and customer protection.

Licensing: The debate is generally in favour of giving market access to mobile network operators (MNOs). This is particularly encouraged by the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSMA), but also organisations such as the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) (see Grossman, 2017). According to the GSMA, regulators should create an open and level playing field that allows both banks and non-bank providers to offer storage and payment services (see Maina, 2018). Furthermore, they should regulate the type of services (payments, savings, credit, etc.) but not the entity. DFID and Bankable Frontier Associates (see Porteous, 2006) also advocate the entry of MNOs, which enjoy strong retail networks, in particular given the weakness of the retail banking sector in many developing countries.

AML/CFT and KYC: The fact that mobile money can be sent easily and rapidly between users has AML/CFT raised. A consensus has emerged around proportional and risk-based regulation (Maina, 2018; Webb Anderson, 2014; Staschen and Meagher, 2018), in order to prevent AML/CFT activities without hindering the development of mobile money. Risk can be mitigated by imposing limits on the value and frequency of transactions and on account functionality. A risk-based approach to AML/CFT is especially important in countries that lack a universal national identity system. Similarly, a tiered approach to KYC (Know Your Customer) is proposed because it allows the financial regulator to distinguish between lower and higher risk scenarios (Maina, 2018; Porteous, 2006; Webb Henderson, 2014; Staschen and Meagher, 2018; Logan, 2017; Grossman, 2017).

Agent Network: There is a consensus toward a light-touch approach where the obligations are placed on mobile money providers to ensure the integrity of agents. Furthermore, GSMA (Maina, 2018) and Webb Henderson (2014) advocate a notification regime where providers notify the central bank of all third parties, instead of requiring authorisation. This can also reduce the burden of the regulator.

Inter-operability and agent non-exclusivity: Inter-operability allows customers to transact using mobile money across different MNO platforms and agent non-exclusivity allows agents to serve more than one MNO. There is consensus on ensuring inter-operability and agent non-exclusivity, although the question remains as to whether that should be market-led or regulator-led. Inter-operability brings value to customers, by allowing them to switch easily between providers but also increases competition, which may deter potential entrants. Thus regulators need to find a balance between premature competition regulations, which may slow the growth of mobile money, and a delaying competition regulation, which may allow an MNO or bank to build up a dominant position. Therefore, it is key that operability is implemented at the right time. There are also further benefits to inter-operability: it expands the pool of customers for providers and minimises the need for retail agents to have cash, which is costly to move around between different agents.

Customer protection: There is an obvious consensus around the fact that customers should be adequately protected against fraud and abuse with regards to mobile money. Customer protection also concerns matters of privacy and data protection; customers’ trust in the system is key for its development and growth. Webb Henderson (2014) suggests that the provider or its agents distribute plain-language product information documents at the time of registration, which should contain key information relating to money services (transaction fees, charges, complaint handling processes, privacy and data protection policies, etc.) and the different roles and obligations of the provider. The World Bank (2012) suggests that governments could support the education of customers in mobile money products through promoting transparent business practices.

Other issues: The question of taxation of mobile money transaction has also been raised. However, the GSMA (Maina, 2018) points out that taxation of mobile money should not fall disproportionately on those with lower incomes. In addition, taxation should not disincentive efficient investment or competition in the mobile money industry.

Typical regulation trajectories

We outline in the box some of the typical steps and decisions adopted over the course of a regulatory trajectory. This is based on the analysis of three case countries (Tanzania, Bangladesh, Myanmar), from the initial approach to mobile money, to a wide diffusion of the service, including the offerings of a larger range of new digital financial services products, such as loans, deposits and insurance (our research, 2019a).

STEPS THROUGH MOBILE MONEY REGULATION - A typified trajectory

Step 1: The Central Bank issues a letter of no objection or directive. It also makes the decision on bank-led or telco-led model.

This step can follow initial entry of mobile money players, or approach of the Central Bank by players as there may be no pre-existing regulation.

Step 2: Clarification of the playing field and entry of more players

Competition increases. A significant share of OTC transactions might be observed, especially if players are lenient in order to increase market share.

At this stage further regulations may be passed (Acts, etc.)

Step 3: Decisions regarding:

- Move to opening up to telco in some previously bank-led cases (cf Myanmar or India)

This might happen if the regulator believes MNOs’ entry will increase access. It might depend on the strength of the banking sector (lobby) and its ability to block MNOs from entering the market.

- Move to interoperability

This might be market-led or regulator-led. It might be easier to impose it on players than to wait for a market-led solution.

- Enforcement of prohibition of OTC

Regulations against OTC transactions may be enforced as the volume of transaction grows and the population becomes more familiar with the system. OTC transactions pose AML/CFT issues, related to lack of KYC information.

Step 4: Decisions regarding:

- Taxation of mobile money

When the mobile money ecosystem is well-established the government might impose taxation on customers’ transaction.

- Adoption of new digital financial services products, such as loans, deposits, insurance, etc.

At this stage further regulations may be passed (Acts, etc.)

This might happen if the regulator believes MNOs’ entry will increase access. It might depend on the strength of the banking sector (lobby) and its ability to block MNOs from entering the market.

- Move to interoperability

This might be market-led or regulator-led. It might be easier to impose it on players than to wait for a market-led solution.

- Enforcement of prohibition of OTC

Regulations against OTC transactions may be enforced as the volume of transaction grows and the population becomes more familiar with the system. OTC transactions pose AML/CFT issues, related to lack of KYC information.

When the mobile money ecosystem is well-established the government might impose taxation on customers’ transaction.

- Adoption of new digital financial services products, such as loans, deposits, insurance, etc.

Initial policy recommendation

Our key findings and policy recommendations are:

1. It is fundamental to give access to mobile network operators while encouraging partnerships between banks and telcos to develop further mobile money services (microloans, microinsurance, etc.) and strengthen the economy-wide impacts of mobile money.

2. Inter-operability should be encouraged by the regulator once the ecosystem has graduated from the incipient phase.

3. Ensuring customer protection is key to strengthen trust in the system. This goes hand in hand with strong agents’ training and support and customers’ education in mobile money usage. The last point is particularly important given that, in some countries where mobile money is particularly developed, most of the transactions occur over the counter (OTC). OTC transactions reduce mobile money’s scope for financial inclusion while increasing the risk of fraud.

Authors’ note: Our research was funded by grants from The Leverhulme Trust, International Growth Centre, and the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ papers Innovation in Emerging Markets: The Case of Mobile Money. 2019, LSE mimeo, and Mobile Payment Systems in Developing Countries, 2019a, LSE mimeo.

- The post gives the views of the author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

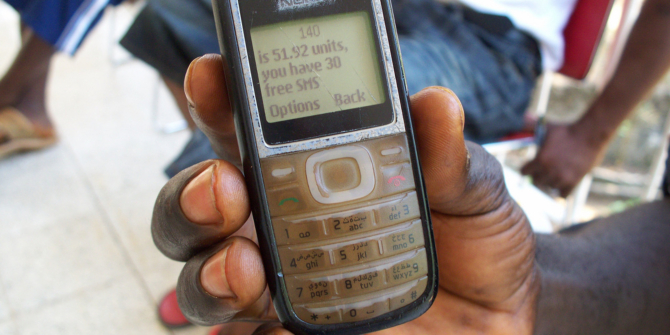

- Featured image by Institute for Money, Technology and Financial Inclusion, under a CC-BY-SA-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Adeline Pelletier is a lecturer in strategy at Goldsmiths College’s Institute of Management Studies. Previously, she was assistant professor in business administration at Instituto de Empresa (2015/16) and postdoctoral researcher affiliated to LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). a.g.pelletier@lse.ac.uk

Adeline Pelletier is a lecturer in strategy at Goldsmiths College’s Institute of Management Studies. Previously, she was assistant professor in business administration at Instituto de Empresa (2015/16) and postdoctoral researcher affiliated to LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). a.g.pelletier@lse.ac.uk

Susanna Khavul is Leverhulme visiting professor at LSE, and an associate at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) and International Growth Centre (IGC). She is faculty at the Lucas College and Graduate School of Business at San Jose State University. Email: s.khavul@lse.ac.uk

Susanna Khavul is Leverhulme visiting professor at LSE, and an associate at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) and International Growth Centre (IGC). She is faculty at the Lucas College and Graduate School of Business at San Jose State University. Email: s.khavul@lse.ac.uk

Saul Estrin is professor of management and strategy and a member of CEP at LSE. s.estrin@lse.ac.uk

Saul Estrin is professor of management and strategy and a member of CEP at LSE. s.estrin@lse.ac.uk