Across the world, many people aren’t saving enough money to be able to retire from work, or to be prepared for emergencies. Some of these people have very low incomes, but others earn a lot, they just spend most of it. Personally, I’ve been in both situations. In the years before I went to graduate school, I worked in retail and had low-paying freelance jobs; I lived on credit cards and never felt able to put money aside. After I finished graduate school and landed a job at LSE, my income was much higher—but somehow, I found myself still living paycheck to paycheck.

My interest in understanding my own spending and saving decisions led me to start studying this topic. Around the 2008 financial crisis, lots of people speculated that what we needed was more financial education training. Unfortunately, research (done by others) suggests that most of this training has no effect on people’s finances. Other research points out that humans seem hard-wired to value the present, making it harder to save for the future. But there’s still a lot we don’t know.

In this research project we’ve designed a computer game to let us scientifically study spending under controlled conditions, using imaginary money, with people ages 8 and up. This game has been programmed by Expilab, which specialises in making research tools that are realistic and engaging. We want to know, in a large and varied group of people of different ages, how choices about spending money are affected by things that are important in the real world, like how much you start off with, how regularly you get income, and how other people around you are spending their own money.

We study these questions by building in some variations of the game—some people get a large amount of imaginary money to start and others get a small amount, for instance. The game lasts for 12 “months” and each month a player either gets income (“gold”) or does not, and then decides how much to spend. People play both with and without information about how their score compares to other players, so that we can see how people’s decisions change depending on what they see others doing. The game is meant to be fun, too!

The problem of insufficient savings—and the stress that goes along with it—has become increasingly visible in the last few years. However, most of us still don’t feel comfortable talking about money, even with close friends. Not knowing how much others spend and save can make it harder to know what we ourselves should do, and harder to support those who need help. One of our goals for this project is to break down a bit of the taboo around money, by giving people a way to start new conversations.

More than 2,000 museum visitors completed some part of the research. They played ‘The Game of Life’, where they were given some ‘gold’ and had to decide how much to spend each month over 12 months. The basic screen looked like this:

Figure 1. The Game of Life’s basic screen

Here are a few of the things we found out, using the game:

1. People with predictable patterns getting gold did best

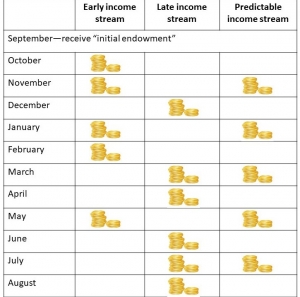

We created three different income streams by varying the months in which people were given gold.

Figure 2. The different income streams offered

People who were randomly assigned to the early income stream got most of their gold in the early months. They earned 753 points on average. People with the late income stream got most of their gold in the ending months. They earned 762 points on average. Finally, a third group of players had a predictable income stream—a month off, a month on. Many people in this version actually told us that they figured it out and they knew that money was coming every second month. In this case they were able to use their money more advantageously. They scored 855 points on average, which is more than participants with the irregular early or late income streams.

There has been a lot of attention recently given to the challenges of coping with unpredictable income, like what people experience when they have a zero-hours contract. Our research reinforces the argument that budgeting can be much easier—and people can be more successful—when income is predictable.

2. People did worse when they were in a group with high-scoring others

Figure 3. The leader board presented to participants

Those who took part in the first two weeks of the study didn’t see anyone else’s score (unless they were peeking at a friend’s screen…). At the end of the first two weeks, we put people into groups to play the game, so you saw how your score compared to seven other group members. The group all had the same initial endowment (but may have had different income streams). In these versions, participants saw a leader board.

We built three different types of groups by drawing either mostly very high-scoring players, mostly low-scoring players, or a range of players (an ‘average’ group). Those who played alone earned the highest scores on average (823 points) compared to those who played against bad groups (798), average groups (764), or very good groups (700). If the low scores are because people spent too much, then these results are similar to what other researchers have found; the pressure to move up in a group makes many people spend more than they should, and their final score suffers.

3. The game seems to reflect people’s real financial decisions

One of our goals with this project was to see whether the way people play in the game reflected the way they manage their money in real life. We did this by including some questionnaires after the game that measured different aspects of how people manage their own money. With visitors over 16, for instance, we asked: “Imagine you had an unexpected expense of £1,500. How likely is it that you could pay this amount, in full and on-time, without borrowing or using credit?” Taking into consideration all the variations above, people who scored higher in the game said this was more likely.

People who scored high in the game also reported being less stressed about their own money currently (although not any more likely to expect that they’d be financially secure in the future!). These results suggest there is something about this game that measures the way people spend their money, and so the game may be useful for future research. For example, if an employer wanted to see whether the financial training they give to employees was effective, they could use this game to get a fast answer, instead of waiting months to see how the employees’ spending might change. We’ll have to do some more research to see exactly how this could work, but we’re excited about the possibility.

4. Other questionnaire measures also related to game scores.

We gave some questions that measure numeracy, which are drawn from those that the Money Advice Service has used. Not all participants saw these questions or chose to answer them—many groaned about seeing maths! But among the nearly 1,000 who did, there was a strong relationship between numeracy scores (getting more questions right) and scoring highly in the game. You can test your numeracy here and work on improving it here, if you’re interested.

Figure 4. A participant playing the game

Source: Photo courtesy of ©The Science Museum, NOT under Creative Commons

5. A couple of final points.

Visitors from other countries (of which there were 569) did not perform differently on average than those from the UK (1,451 of them) and there was no difference between men and women. People who reported being more materialistic scored lower at the game, but this was only true for adults and not for children. It might be because the children’s questions are different, or because some children didn’t really understand well how to play the game. When people don’t understand how to play, there is more ‘noise’ variation (differences that are not meaningful), which makes it harder to see effects. (Do keep in mind that finding a relationship between two measures, like between materialism and game scores, certainly doesn’t mean one of these things causes the other one).

We had a lot of young participants, especially during the half-term week. We asked those who were under 16 years old: “How confident do you feel managing your money?” The good news is that most felt very confident; almost all the answers were between 5 and 10 on the 10-point scale. The possibly bad news is that these answers were unrelated to scores in the game, so some young people (and some adults) may be more confident than they should be.

In conclusion…

We’ll be looking further into this data to learn more about spending in the coming months. If you’re interested in playing the game in the meantime, you can play it here. This project was motivated in part by the fact that money is a taboo topic; most of us don’t feel very comfortable talking about it, and this makes it hard to learn. I hope playing the game helps make it easier to talk about money, so please do feel free to share it with anyone that might be interested.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The ‘Science of Spending’ project was made possible by funding from LSE’s Knowledge Exchange and Impact (KEI) fund, and run with help from Rebecca Campbell and five students from the MSc Marketing programme.

- This blog post appeared first on LSE’s Department of Management blog.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image via pxhere, Public domain

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Heather Kappes is an assistant professor of marketing in LSE’s department of management. She takes a behavioural science approach to marketing, trying to understand what influences people as they pursue their goals (for instance, to run a race or to save money). Her current research looks at how adults and children think about wealth and spending, and how their beliefs predict their spending and financial resilience. Heather has a PhD in social psychology at New York University, and a BS in biopsychology from the University of California, Santa Barbara. She sometimes uses physiological measurements, like systolic blood pressure and heart rate variability, to help understand how people respond to different kinds of information and make decisions.

Heather Kappes is an assistant professor of marketing in LSE’s department of management. She takes a behavioural science approach to marketing, trying to understand what influences people as they pursue their goals (for instance, to run a race or to save money). Her current research looks at how adults and children think about wealth and spending, and how their beliefs predict their spending and financial resilience. Heather has a PhD in social psychology at New York University, and a BS in biopsychology from the University of California, Santa Barbara. She sometimes uses physiological measurements, like systolic blood pressure and heart rate variability, to help understand how people respond to different kinds of information and make decisions.