China is the world’s largest user of industrial robots. In 2016, sales of industrial robots in the country reached 87,000 units, accounting for around 30 per cent of the global market. To put this number in perspective, robot sales in all of Europe and the Americas in 2016 reached 97,300 units (according to data from the International Federation of Robotics). In addition, between 2005 and 2016, the operational stock of industrial robots in China increased at an annual average rate of 38 per cent.

What is driving the rise of robots in China? In a recently published article, we dig into the underlying factors behind the country’s rise to the forefront of industrial robotics. Through a new survey, the China Employer-Employee Survey (CEES), we have collected some of the world’s first firm-level data on robot usage and provide possible explanations from both the supply and demand sides.

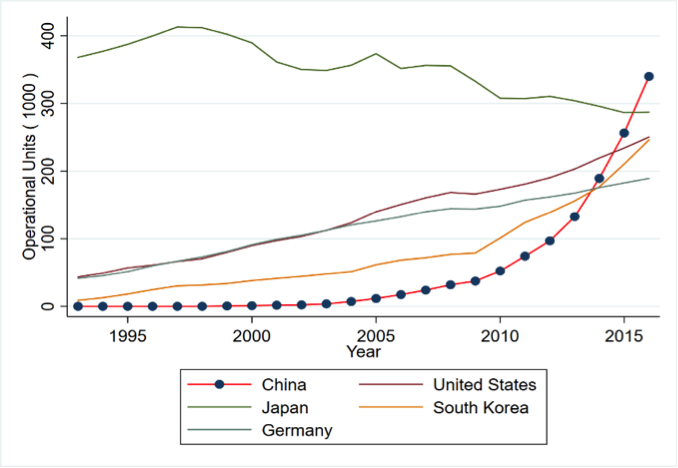

Figure 1 charts the dramatic ascendency of robots in China. The top five robot markets in the world — China, Japan, the United States, South Korea, and Germany — accounted for 72 per cent of the world’s operational robot units in 2016. In the past decade, China has surged to 339,970 operational units in 2016, accounting for 19 per cent of the total worldwide stock.

Figure 1. Stock of operational robots in major countries 2016

The interplay of market factors and government policies

The industrial composition of robot adoption in China mirrors other major robot markets like Japan, the United States, South Korea, and Germany. The automotive and electronics industries have the highest rate of robot use, accounting for 69.2 per cent of total stock. This has implications for the future of robots in China. The country has been the world’s largest national producer of automobile units since 2008: indeed, since 2009, the Chinese annual production of automobiles has exceeded that of the United States and Japan combined. China also clearly dominates the global electronics industry: over 70 per cent of the world’s computers and electronics are made in China. These industries seem likely to keep expanding, which implies that China will become an even more significant user of robots.

We examine two sets of factors on the demand side. The first is the declining growth of the working-age population and rising wages, something many economies are dealing with. The second, which may be specific to China, is the government’s industrial policies driven by the imperative to lead a new wave of Industrial Revolution.

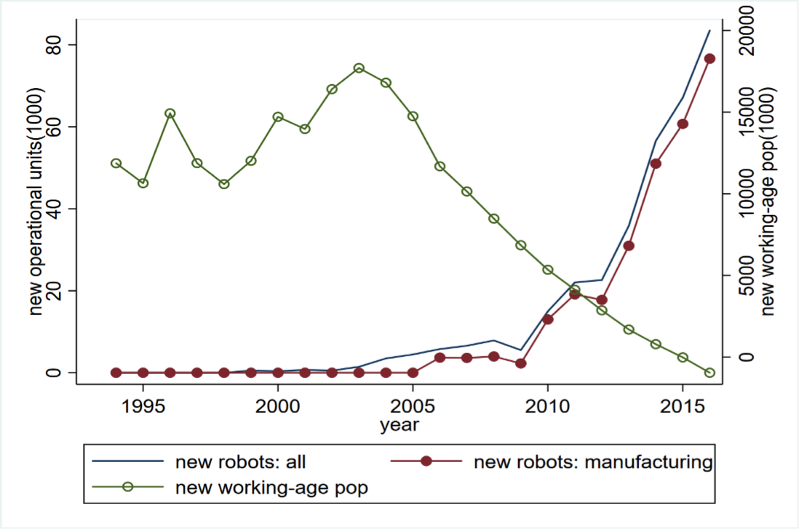

Figure 2 plots the annual increase in working-age population. It peaked in 2003 at around 17.7 million, but has declined since then and turned negative in 2015. Wages of urban workers are also rising. From 2005-2016, China’s average annual growth rate in real wage was 10 per cent (adjusted by China GDP deflator) for those employed by urban units, and the annual wage growth rate for the manufacturing sector was 9.7 per cent. In this respect, the robot revolution in China reminds us of how high labour costs accompanied the Industrial Revolution in historical contexts like Britain and the United States (e.g., Habakkuk 1962, Allen 2009), as well as recent cross-country analysis on demographics and automation by Acemoglu and Restrepo (2018).

In addition to these market factors, the Chinese government has aggressively promoted the production and use of industrial robots in recent years. In 2013, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) released its “Guidance on the Promotion and Development of the Robot Industry.” These initiatives were further bolstered in 2015 by the launch of the “Made in China 2025” program, which set national goals of producing 100,000 industrial robots per year and achieving a density of 150 robots per 10,000 workers by 2020, tripling the robot density in the manufacturing sector reported for 2015. In addition, in 2016, the MIIT, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), and the Minister of Finance jointly launched the Robotics Industry Development Plan (2016-2020) to promote robot applications to a wider range of fields including the service sector.

Figure 2. Declining growth in population aged 15-64

In our firm-level data, we find patterns suggesting that both factors – labour market forces and government policies – matter for firms’ decision of robot adoption. Larger firms, firms with higher capital-labour ratios, and firms with higher wage bills were more likely to adopt robots. Looking at labour turnover, voluntary labour turnover was positively correlated with robot adoption, while involuntaryturnover was not (suggesting that turnover was a cause, not a consequence of robot adoption). Additionally, 15 per cent of robot-using firms had received subsidies specific to robot adoption, and firms with a Communist party member as CEO were also more likely to adopt robots.

The current techno-optimism

Given its aggressive promotion of robot adoption and production via industrial policy, the Chinese government does not seem to fear the consequences of disruptive robotic technology. Similarly, in our interviews with employers and employees, we did not find that they are nervous about job replacement. In light of these perhaps surprising findings, we offer a few possible explanations for why China embraces robots, from the perspectives of the government, the employers, as well as the workers.

Government policies are motivated by the challenges of labour costs and labour shortage, as well as the imperative to lead a new wave of Industrial Revolution. The Chinese government sees robotics (and automation) as a positive phenomenon, an advance in science and technology essential to China’s rise as a world power. For example, a 2016 State Council plan states that “China fell into backwardness and took beatings in the modern era [because] previous industrial revolutions slipped through our fingers … To realize the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nationhood that is the Chinese Dream, we must make genuine use of science and technology, this revolutionary force and lever of power in the highest sense.” We see the long shadow of history here, as this perception partly originates from China’s painful early encounters with Western powers. Since the Opium War in the 1840s, China has endured numerous foreign invasions, which many have attributed to the inferiority of technology in China.

For employers, labour force challenges are indeed important considerations for robot adoption, as suggested by our firm-level analysis. For employees, high voluntary turnover rates and the lack of strong and independent unions may partly contribute to their tolerance of robot adoption.

It is conceivable, however, that the short-run consequences are different from those in the long run. We hope to make further progress on these questions by continuing to follow China’s manufacturing firms.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper The Rise of Robots in China, in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol 33, No. 2, Spring 2019.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image (Shanghai Street) by Michael Elleray, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Hong Cheng is the director of Wuhan University Institute of Quality Development Strategy and editor-in-chief of Macro-quality Research. He is a pioneering figure in the industry of “Macro-quality Management” in China, publishing the first academic monograph Macro-quality Management. He has received numerous awards. Prof. Cheng is also the lecturer for theoretical study of the Party Committee Center Group and workshops tailored for government officials in more than 10 provinces and cities including Guangdong and Hubei Province.

Hong Cheng is the director of Wuhan University Institute of Quality Development Strategy and editor-in-chief of Macro-quality Research. He is a pioneering figure in the industry of “Macro-quality Management” in China, publishing the first academic monograph Macro-quality Management. He has received numerous awards. Prof. Cheng is also the lecturer for theoretical study of the Party Committee Center Group and workshops tailored for government officials in more than 10 provinces and cities including Guangdong and Hubei Province.

Ruixue Jia is an associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, School of Global Policy and Strategy (GPS). She focuses her research on the political economy, development economics, economic history and China. Jia uses organization theory to closely examine the incentives of politicians, particularly to understand how such incentives affect growth, the environment and workplace safety.

Ruixue Jia is an associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, School of Global Policy and Strategy (GPS). She focuses her research on the political economy, development economics, economic history and China. Jia uses organization theory to closely examine the incentives of politicians, particularly to understand how such incentives affect growth, the environment and workplace safety.

Dandan Li is with the Institute of Quality Development Strategy at Wuhan University.

Hongbin Li is the James Liang director of the China Program at the Stanford Center on Global Poverty and Development, and a senior fellow of Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR). He obtained Ph.D. in economics from Stanford University in 2001 and joined the economics department of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). He was a founding director of the Institute of Economics and Finance at the CUHK. He taught at Tsinghua University in Beijing 2007-2016. He also founded and served as the executive associate director of the China Data Center at Tsinghua. He co-directs the China Enterprise Survey and Data Center at Wuhan University.

Hongbin Li is the James Liang director of the China Program at the Stanford Center on Global Poverty and Development, and a senior fellow of Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR). He obtained Ph.D. in economics from Stanford University in 2001 and joined the economics department of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). He was a founding director of the Institute of Economics and Finance at the CUHK. He taught at Tsinghua University in Beijing 2007-2016. He also founded and served as the executive associate director of the China Data Center at Tsinghua. He co-directs the China Enterprise Survey and Data Center at Wuhan University.

Dear LSE Business Review Team,

thank you for this interesting article.

As the press officer for the International Federation of Robotics (IFR) I like to let you know that the IFR statistics you are using are not up-to-date. Currently the 2017 robotics data is available and In September there will be the publication of the new IFR World Robotics Report 2019 in Shanghai with the statistics 2018.

Best regards

Carsten Heer

International Federation of Robotics

IFR Press Office

econNEWSnetwork

Carsten Heer

Tel.: +49 (0)40 8 22 44 284

Mob. + 49 (0) 15 737 511 823

Carsten.Heer@econ-news.de

press@ifr.org

http://www.ifr.org

.