Are you worried about big businesses and monopoly? Perhaps you should be, because they can charge you high prices and give you low-quality services. That’s why we have antitrust law in America and competition policy in Europe to stop companies from buying up each other and merging into monopoly.

But that’s not the whole story. Technologies come and go, taking generations of companies with them. When innovation is important, the economic argument for blocking mergers breaks down, or almost breaks down.

Why? For one thing, monopoly could be the result of successful innovation in the past. If a company makes a great new product and others can’t compete with it, an industry champion is born because of innovation. Another point is that the promise of monopoly profit might stimulate innovation in the future. Business is not charity after all, so showing some carrots helps investment in technology. In short, monopoly might be the result of innovation, and monopoly might be good for innovation.

Economists have been arguing about the relationship between competition and innovation for almost a century. Some school say competition increases innovation; others say competition decreases innovation. And then there’s a cult of the “inverted U,” which believes a little bit of competition is good, but too much competition is bad. They couldn’t finish the debate, because theory says almost anything can happen, and empirical researchers have a hard time running “experiments” in real industries.

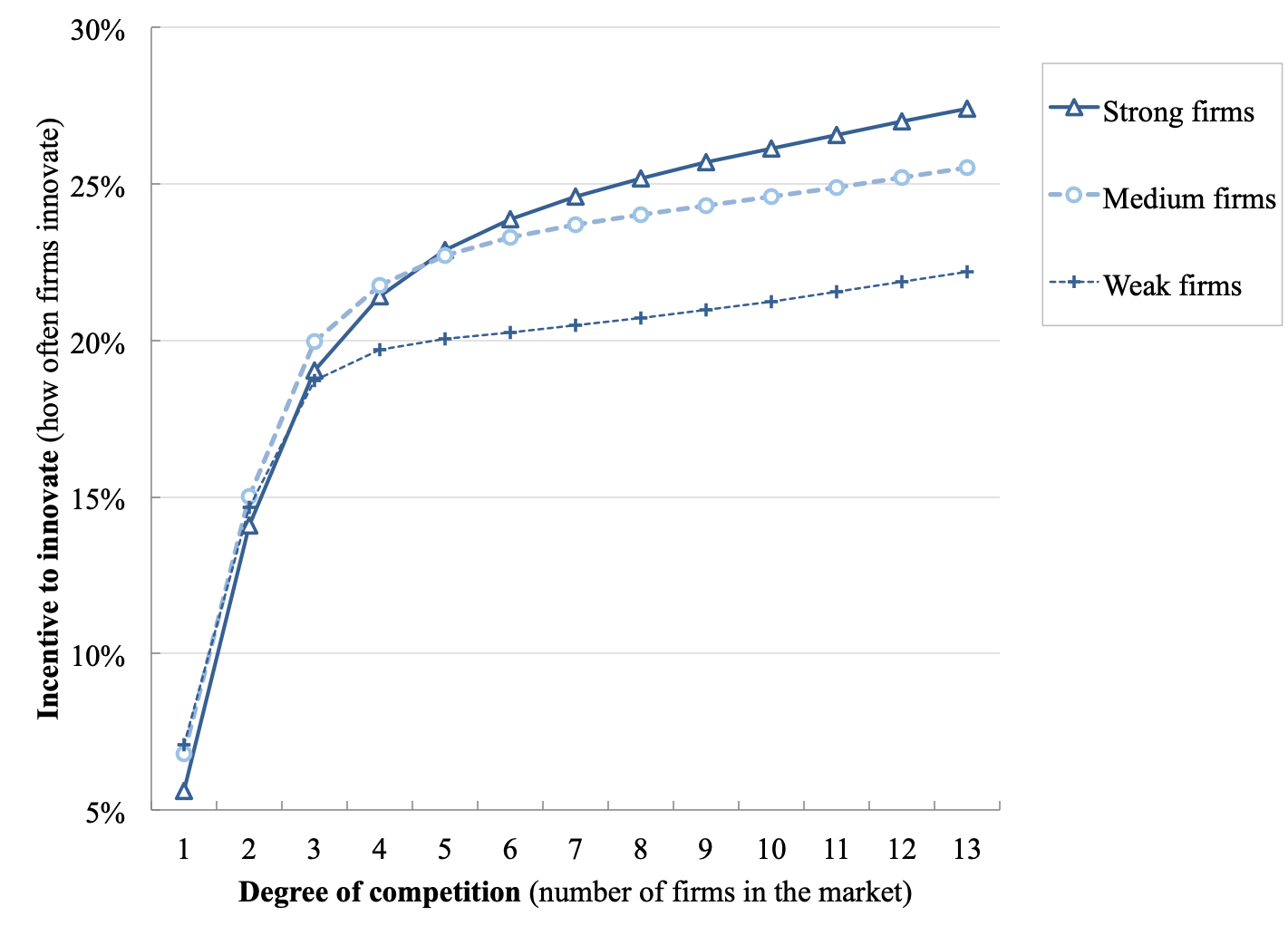

Our new research shows that the competition-innovation relationship actually looks like Figure 1, at least in the global high-tech industry of hard disk drives (HDDs) that we scrutinised. So who was right? With our Japanese politeness, we’d like to say everyone was almost right. The graph shows the incentive to innovate increases with competition at first, but then this positive effect tapers off when more than four or five firms compete in the industry.

Figure 1. Innovation increases with competition and then it plateaus

Why is monopoly bad for innovation? Ask yourself: are you going to work if you don’t have to? By contrast, companies want to innovate more in a market with two, three, or four competitors. Better products (and/or lower costs) will make you more competitive than your rivals. You’ll make more money, people will love you, and you’ll feel good about yourself.

But then, why don’t companies innovate even more when they face five, six, … many competitors? There are some subtleties. Case 1: if you are really strong, you don’t care whether your competitor number 13 is dead or alive. Case 2: if you are weak, you are hopeless and wouldn’t bother investing in new technology, because you are likely to quit anyway.

So our bottom line is that “plateau” is the new “inverted U.”

At this point, let’s get back to the original question: how far should an industry be allowed to consolidate? The conventional wisdom says three firms are good. That has been the rule of thumb, and de-facto policy in regulating high-tech mergers. The problem is that no one has proved it’s the right policy or explained in what sense this is a good policy. Now we can.

For a thought experiment, suppose President Donald Trump (or whoever succeeds him) abolishes antitrust law, and the European Commission closes its competition-policy arm. Now all mergers become possible for sure, including ones that create monopoly.

Two things will happen. One: more companies will enter the industry, and they will make a lot of investments. More firms and investments mean more competition and innovation, at least in the early stage of the industry’s history. The reason is that now the industry becomes appealing to managers and investors, because they know they can eventually merge with each other and make monopoly profit. Alternatively, they can be bought out by such champions for good acquisition prices. Doing business in this kind of environment is more valuable, so let’s call it the “value-creation” effect of relaxing merger regulation.

Two: however, both competition and innovation will suffer when the industry matures and merger waves actually happen. Now that there are fewer firms, they will compete less aggressively and invest less in technology. Consumers will eventually suffer from high prices, low quality, and poor services. Unfortunately, this “anti-competitive” effect is much bigger than the value-creation effect when we crunch numbers for the entire lifecycle of the industry. The exact balance between these economic forces might vary by industry and technology, but they are always there.

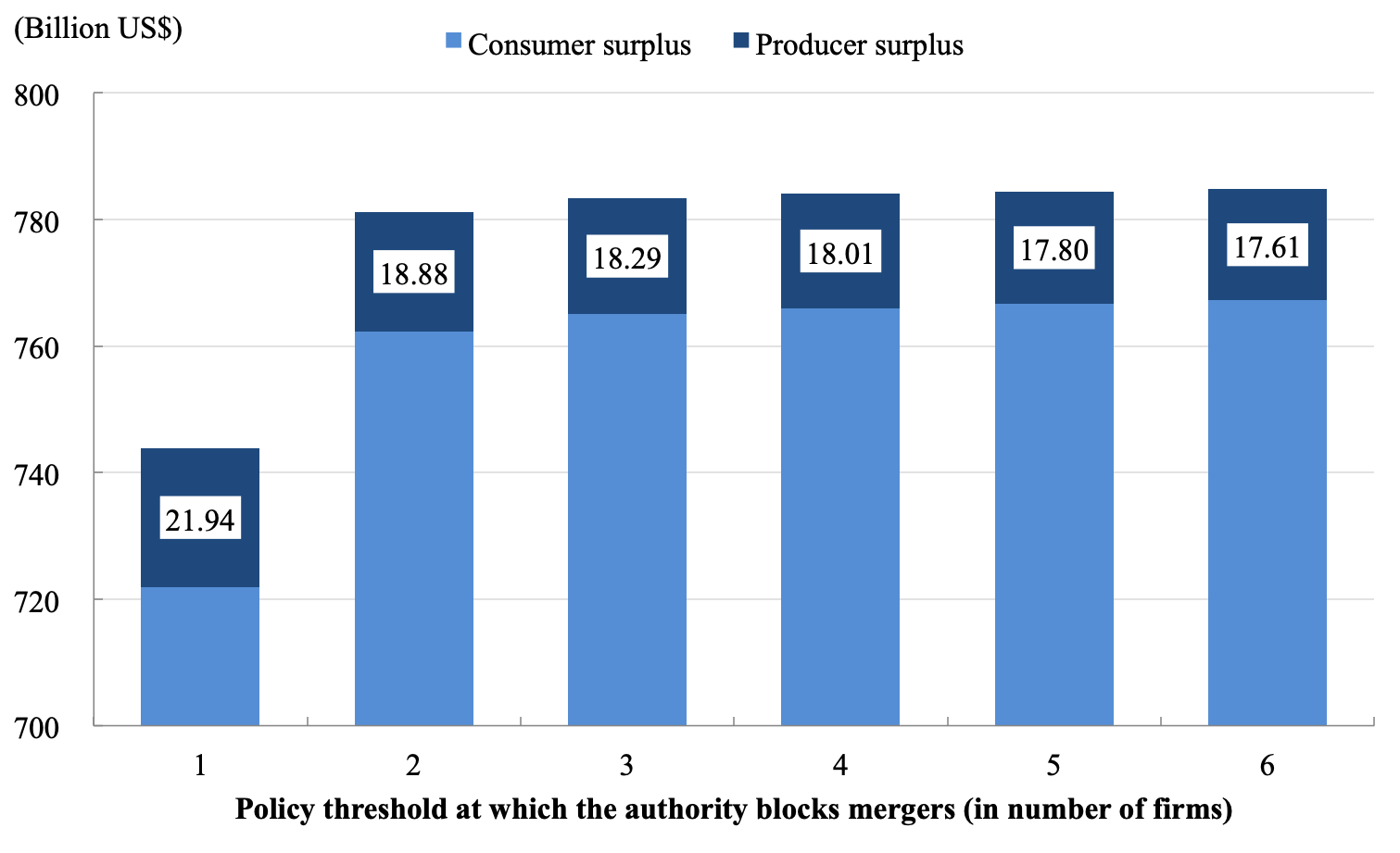

That’s why the long-run “social welfare” (i.e., a measure of total happiness that economists use for evaluating the performance of a market) is low under “zero antitrust” policy or “hardly any antitrust” policy (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Long-run social welfare

O.k., so abolishing antitrust looks like a bad idea. How about moving in the opposite direction, blocking mergers more aggressively when there are still four or five firms in the industry?

It turns out social welfare increases but only negligibly. That’s because regulation can promote competition only so much. Antitrust authority can block mergers but can’t stop weaker companies from going bankrupt, just like police might be able to prevent murders but not natural deaths.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ research article, “Mergers, Innovation, and Entry-Exit Dynamics: Consolidation of the Hard Disk Drive Industry, 1996–2016,” in The Review of Economic Studies.

- This blog post gives the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Tony Webster, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Mitsuru Igami is an associate professor of economics at Yale University.

Mitsuru Igami is an associate professor of economics at Yale University.

Kosuke Uetake is an associate professor of marketing at Yale University.

Kosuke Uetake is an associate professor of marketing at Yale University.