Half of the electorate are women. Research has consistently shown that women are more likely to be floating voters and to make their minds up on how to vote later than men. Securing women’s votes is increasingly recognised as essential for parties as they seek to consolidate their voting base and capture undecided voters. This is something we have observed in our analyses of the 2015 and 2017 manifesto offers for women.

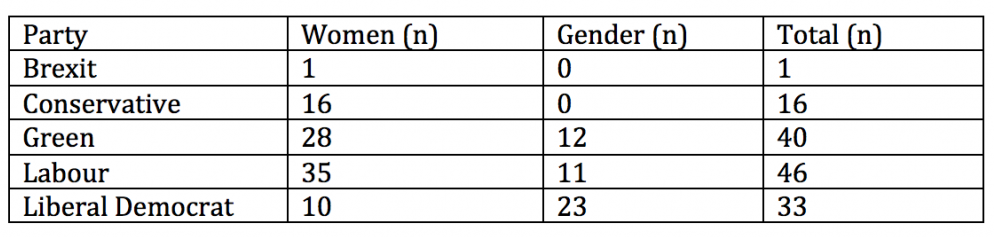

For the 2019 General Election, we audited the party manifestos of all GB-wide parties to see what they offer women. Quite crudely, we counted the number of times ‘women’ and ‘gender’ were mentioned in each manifesto. This in itself was quite revealing, but by no means tells us the whole story. Some mentions of ‘women’ were just headings, not commitments, and, in the case of the Conservative manifesto, one policy to benefit women was repeated three times.

Figure 1. Mentions of ‘women’ and ‘gender’ in 2019 party manifestos

So we then looked again to identify exactly what is being offered when ‘women’ or ‘gender’ is mentioned, and to which women parties were trying to focus their pitch. This is also imperfect because it only captures manifesto pledges that specifically identify women as beneficiaries or have gender equality as the goal. It does not identify policies that we know would particularly benefit women but are not labelled in that way. For example, Labour’s pledge of a ‘real living wage of at least £10 per hour for all workers’ would be of particular benefit to women as they are more likely to be low paid, but this is not flagged in the manifesto. Caveats aside, here’s what we found.

Which women?

All parties – except Brexit – show a substantial awareness of the need to address women voters directly and in all their diversity. Some policies are clearly intended for all women but many are targeting specific groups. Research shows that age is a particular issue in how women vote, with younger women being more likely to support public spending and oppose austerity. Working women thus receive a fair deal of attention, with the Conservatives focusing on supporting female entrepreneurs and self-employed women. Labour also offers measures to tackle employment protection for pregnant women, and an increase in paid maternity leave to 12 months. The Greens specifically address women of childbearing age with pledges on safe and affordable abortion, free birth control, and high-quality maternity care. There are also some manifesto pitches for older women, such as WASPI (Women Against State Pension Inequality) women (below).

All parties except Brexit have something to offer vulnerable and marginalised women with commitments to take action on violence against women and girls, pledges to establish misogyny as a hate crime (Greens and Labour), support for women in the criminal justice system (Greens and Lib Dems), and women with learning disabilities (Lib Dems). LGBTQ women are addressed by Labour, Greens, and Lib Dems with commitments to reform the Gender Recognition Act (Labour), remove the spousal veto so that married trans people can acquire their gender recognition certificate without having to obtain permission from their spouse (Lib Dem and Greens), and offer asylum to people fleeing the risk of violence because of their sexual orientation or gender identification (Lib Dems).

Notably, all parties – again except Brexit – address the status of women internationally, offering policies to consider gender equality and women’s empowerment in trade deals (Conservatives), provide funding for women’s grassroots organisations internationally (Labour), ‘increase the proportion of aid paid to individuals through electronic cash transfers, providing regular monthly payments to women in the developing world’ (Greens) and ‘pursue a foreign agenda with gender equality at its heart’ (Lib Dems).

What for women?

All parties – except Brexit – present a detailed programme of how they would reduce gender inequalities that persist in resources and status. Among these are some ‘big ticket items’: costly policies which, along with promises around the level of the minimum wage, tax thresholds, and the extension of free childcare, have a crucial impact on women’s economic independence and security.

- Brexit: A review of the situation for WASPI women.

- Conservatives: A promise to fund ‘more’ free childcare; leave for carers extended to one week, and a policy to support pension payments for those earning between 11k and 12k, the majority of whom are women.

- Greens: Universal Basic Income, a weekly payment for everyone, replacing the current benefits system, starting with WASPI women and phased in for all residents by 2025.

- Labour: Increasing paid maternity leave from nine to 12 months, doubling paternity leave to four weeks, increasing paternity pay, and extending pregnancy and menopause protection; and full compensation for WASPI women.

- Liberal Democrats: Free, high-quality childcare for children of working parents from nine months; increased paternity leave to six weeks, and compensation for women affected by pension changes in line with the pension ombudsman report.

As well as the maternity leave benefits listed above, the 2019 manifestos have many more policies relating to ‘status issues’ which directly address inequalities that arise from women’s status as women and bodily integrity, such as abortion rights, actions on violence against women and girls and representation. With the exception of the Brexit Party, all parties in varying degrees address status issues:

- Conservatives: Pass the Domestic Abuse Bill and pilot domestic abuse courts; continue to tackle violence against women and girls (VAWG); promote women’s empowerment in free trade deals.

- Green: Reverse funding cuts for women refuges; high-quality maternity care, support for access to abortion and free birth control in the EU; measures to promote diversity in political representation and representation on boards; make misogyny a hate crime and penal reforms to introduce women’s centres; electronic aid payments to women in developing countries.

- Labour: Protection for pregnant workers and women going through the menopause; introduce a workers protection agency around equal pay; appoint a commissioner for violence against women and recognise misogyny as a hate crime; support for international programmes addressing gender inequality, increased funding for women’s grassroots organisations, and an ombudsman to examine abuse in the development sector.

- Liberal Democrats: 40 per cent board representation; foreign policy agenda with gender equality at the heart; protection for women and girls in trade deals; extend reproductive rights and protect against VAWG; set national target to address early deaths of women with learning disabilities; measures addressing VAWG; introduction of gender neutral uniforms in schools.

Additionally there are some ‘blueprint’ measures. These are policies that address the need for overarching gender equality legislation and administrative or bureaucratic resources to oversee progress on equality. These measures are not ever going to appeal to floating women voters. However, the introduction of ‘blueprint’ policies such as the Equal Pay Act (1974) and the Equality Act (2010) fundamentally and profoundly alter women’s rights and measures of redress. Yet in this area, neither Brexit nor the Conservatives promise such blueprint measures.

- Greens: Measures to address the gender pay gap.

- Labour: Establishment of a new department for women and equalities with a full time Secretary of State, a modernised National Women’s Commission; regulation for large firms on equality measures; action on the gender pay gap.

- Liberal Democrats: Extend Equality Act to large firms, and action on gender pay gap.

Our view

It is clear for this election, all parties (though not the Brexit Party) are taking the diversity of women and their interests seriously. They are either offering policies which will benefit women and/or promote gender equality, or they are including promises to do so. Yet it is impossible to form a quick judgement on which party will most successfully attract women voters or to assess the value of their offer.

First, some measures are not specifically targeted at women but we know that they will have a beneficial impact on women – not least because women earn less and do more unpaid caring roles. Both Labour’s living wage promise and the Conservatives’ lifting of the National Insurance threshold will make an impact on women’s incomes if implemented, as will the Liberal Democrats’ promise to considerably extend free childcare.

Second, there is a huge difference between the intent described, ranging from commitments to legislate or regulate, to more ambiguous promises to improve, review, or consider. The Conservative manifesto in particular pledges few concrete measures for women but rather many promises to review or consider, without commitments.

Third, there may be growing scepticism among voters about whether manifesto pledges truly lead to concrete action. At the best of times, governments don’t always deliver what is in manifestos and compromise will inevitably have to be made in the event of another hung parliament or coalition. Economic experts are also sceptical about the affordability of party manifestos and voters will be too. As the Resolution Foundation and the IFS point out, both Conservative and Labour will face fiscal problems in implementing their policy promises.

Fourth, we know from previous research that gender equality promises included in Queen’s Speeches from 1945 onwards – such as redistributive benefits, or equal pay measures – do not reach governmental agendas when the economy is not performing well.

Finally, of course, Brexit might continue to trump everything.

♣♣♣

- This blog post appeared originally on LSE British Politics and Policy.

- The post gives the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Marc Nozell, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Claire Annesley is professor of politics at the University of Sussex.

Claire Annesley is professor of politics at the University of Sussex.

Francesca Gains is professor of public policy at the University of Manchester.

Francesca Gains is professor of public policy at the University of Manchester.

Anna Sanders is a doctoral candidate at the University of Manchester.

Anna Sanders is a doctoral candidate at the University of Manchester.