Crisis management in developing countries is more difficult than in advanced economies. Existing health infrastructure is usually deficient, the large share of the informal economy means a higher cost of the lockdown and subsequent social distancing on businesses, and food production and distribution are more easily disrupted because of border closures, threatening household living standards.

To make matters worse, established mechanisms for reducing poverty may be unavailable for months. For example, in many developing economies school-lunch programs are the main way to get kids fed and attend to their health needs. With schools in many countries closed or “going online,” children who are already vulnerable to dropping out of school may not go back. This is particularly the case for girls. Their future prospects dim.

One of the main challenges in developing countries is the prevalence of informality. Simply put, informal businesses operate in the shadow of the law, avoiding paying taxes but also not providing the security of income and benefits. Research by Rafael La Porta and Andrei Shleifer suggests that informal firms are small, have lower productivity than formal ones, their managers are usually less educated and their employees are often not well-trained. It is difficult for them – workers and businesses alike – to break into the formal economy.

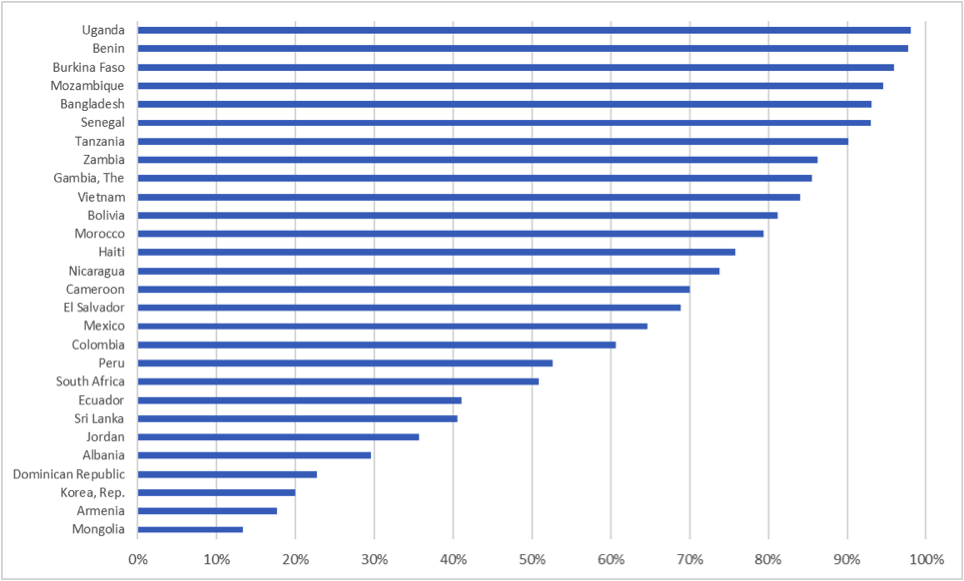

Informality is huge in low- and middle-income countries, accounting for between 13 per cent of workers in Mongolia and 98 percent in Benin, Honduras, Mali and Uganda (figure 1). The data are from the World Bank’s JOIN survey, which provides analysis on social protection for the most vulnerable. The JOIN database contains informality data for 52 countries, often across several years. In 16 countries out of the sample, including Bangladesh and Ivory Coast, the share of informal workers aged 15 to 64 is above 90%. Data across years suggests that some countries have been successful in reducing the level of informality. Ninety-seven per cent of workers were informal in Morocco in 1998, vs. 79 per cent in 2009. In others, the size of the informal sector has remained unchanged over the past quarter century. Mali is an example, where the share of informal workers decreased by only 2% between 1994 (98%) and 2010 (96%). In countries like Chad, the share of informal workers has actually increased to reach near total of the population.

Figure 1. Share of informal workers aged 15-64

Source: World Bank JOIN database

Come the pandemic. Open markets and small shops close, vendors are not able to display their product. Informality, which is a hand-to-mouth business, becomes an even bigger trap. This is because workers in informal businesses are not able to take advantage of the various job retention schemes governments offer. Neither are these workers able to claim temporary unemployment benefits. Furthermore, the business owner herself has no recourse to credit guarantees or small-business grants, also popular as crisis response.

Some governments are considering programs that provide access to crisis assistance in return for firms turning formal. As the research by Miriam Bruhn at the World Bank suggests, this transformation is unlikely to happen. Instead, given good economic opportunity informal business owners are more likely to become wage earners in larger formal businesses. Improved economic prospects apparently help these informal business owners find a job. So, overall, a good post-pandemic recovery plan leads to a more efficient allocation of individuals into occupations.

Governments should view informal businesses as providing subsistence livelihoods to poorer households. To improve their well-being during the crisis, these are best reached through standard cash transfer programs. Countries with existing cash-transfer programs can immediately broaden eligibility and increase the size of the benefit. India is doing just that, according to LSE Professor Swati Dhingra. Given the scale of the economic shock, concerns that better-off households might receive benefits they do not deserve should take a backseat to ensuring that people in need are covered. Additional verification could be carried out later, once the recovery is under way.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Antoine Plüss on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Erica Bosio is a researcher at the World Bank Group, where her work focuses on public procurement. Previously, she worked in the arbitration and litigation department of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton in Milan. She holds a Master of Laws from Georgetown University and a degree in law from the University of Turin (Italy).

Erica Bosio is a researcher at the World Bank Group, where her work focuses on public procurement. Previously, she worked in the arbitration and litigation department of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton in Milan. She holds a Master of Laws from Georgetown University and a degree in law from the University of Turin (Italy).

Simeon Djankov is policy director of the Financial Markets Group at LSE and a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). He was deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. Prior to his cabinet appointment, Djankov was chief economist of the finance and private sector vice presidency of the World Bank. He is the founder of the World Bank’s Doing Business project. He is author of Inside the Euro Crisis: An Eyewitness Account (2014) and principal author of the World Development Report 2002. He is also co-editor of The Great Rebirth: Lessons from the Victory of Capitalism over Communism (2014).

Simeon Djankov is policy director of the Financial Markets Group at LSE and a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). He was deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. Prior to his cabinet appointment, Djankov was chief economist of the finance and private sector vice presidency of the World Bank. He is the founder of the World Bank’s Doing Business project. He is author of Inside the Euro Crisis: An Eyewitness Account (2014) and principal author of the World Development Report 2002. He is also co-editor of The Great Rebirth: Lessons from the Victory of Capitalism over Communism (2014).