Social entrepreneurship is defined by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as “the entrepreneurship that has as its main goal to address pressing social challenges and meet social needs in an innovative way while serving the general interest and common good for the benefit of the community. “In a nutshell, social entrepreneurship targets social impact primarily, rather than profit maximisation in their effort to reach the most vulnerable groups and to contribute to inclusive and sustainable growth”. But what about its own sustainability?

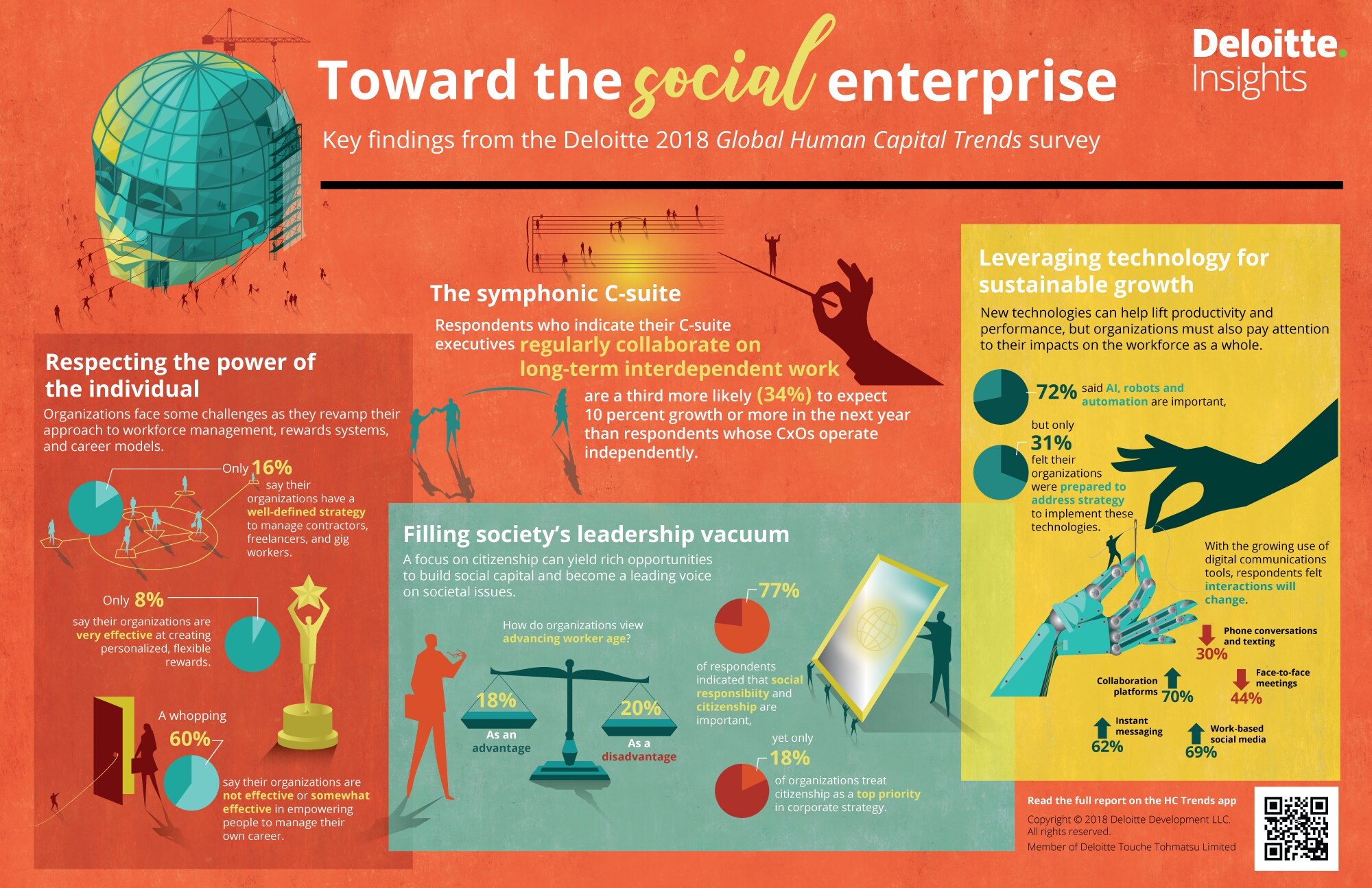

According to Deloitte’s 2018 Global Human Capital Trends report, “a profound shift is facing business leaders worldwide: The rapid rise of the social enterprise, reflecting the growing importance of social capital in shaping an organisation’s purpose, guiding its relationships with stakeholders, and influencing its ultimate success or failure.” Some claim that “the future belongs to social entrepreneurs” or that “the for-profit social enterprise is the impact model of the future,” others call it “a new paradigm for business” or even “the new business model.”

The model’s appeal is evident, The Guardian stating that in the UK “one in four people who want to start a business want to create a social enterprise”, “the sector now accounts for 9% of the small business population, employing 1.44 million people” and “Social Enterprise UK estimates the startup rate is three times that of mainstream SMEs”.

Figure 1. Key findings from the Deloitte 2018 Global Human Capital Trends Survey

“There are big benefits to this model. For-profit enterprises are often more sustainable in the long run, and able to scale more quickly,” a social entrepreneur explains in Forbes. “But there are also big challenges.”

According to The Guardian, the sector has to tackle an image problem affecting its sustainability: 71% of social entrepreneurs “still struggle to make a living from a social venture. The same proportion struggle to find sustainable revenue streams and 60% find it difficult to access the right kind of finance.” The newspaper mentions a social entrepreneur who “despite a number of big wins and 400% growth year-on-year, isn’t sure it’s a sustainable business model.”

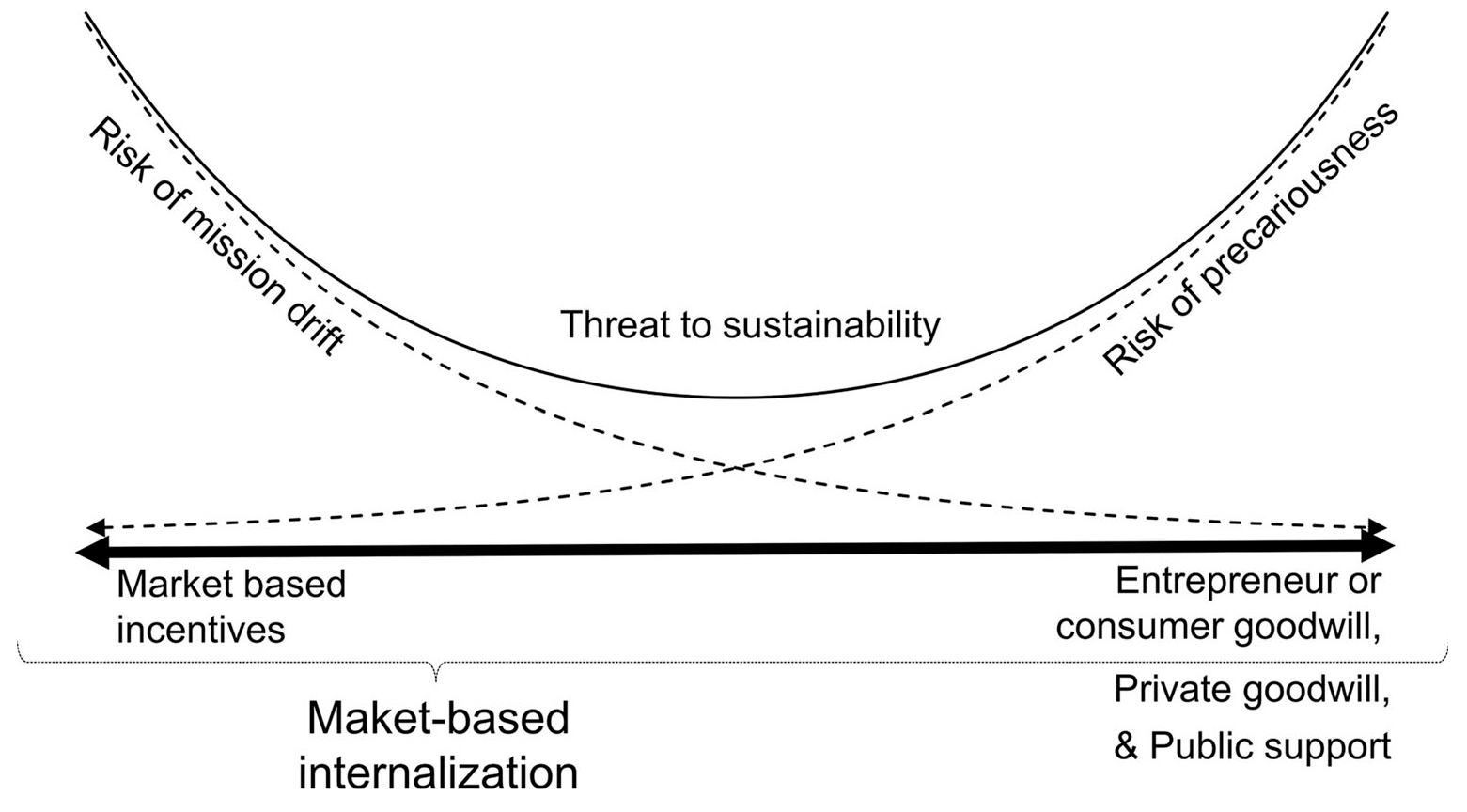

Despite institutional efforts like the European Commission’s social business initiative, social enterprise is in a precarious position, on the razor’s edge between market economics and the voluntary sector: social entrepreneurs have to deal with either the precariousness of the different kinds of support (external or internal) or the risk of mission drift. They must always strike a delicate balance between commercial principles and social concerns. There is no shortage of discussion concerning the possible solutions that could help to maintain this balance, and social entrepreneurs are striving to reconcile conflicting aims on a daily basis, but the economic roots of this precariousness remain.

Figure 2. The dilemma faced by social entrepreneurs between the risks carried by internalisation and by public or private goodwill

Based on an analysis of the root causes of the dilemma that hampers the sustainability of social entrepreneurship, I proposed a new radical (in the etymological sense of the term “root”) approach to this precariousness.

I started by identifying what determines this dilemma: social entrepreneurs have to deal with either the precariousness of the different kinds of support (external or internal) or the risk of mission drift, i.e. the “risk of losing sight of their social missions in their efforts to generate revenue”, which, according to Alnoor Ebrahim and his co-authors, jeopardises “[their] very raison d’être”. What is at stake is their capacity to “handle the trade-offs between their social activities and their commercial ones, so as to generate enough revenues but without losing sight of their social purpose.” As an illustration, the same entrepreneur adds in The Guardian that “my commitment to ethics makes everything more expensive and much more time-consuming. My margins are smaller… and a lot of routes to funding are closed to me.”

This enabled me to define the institutional conditions that might make it possible to overcome it, and to suggest institutional arrangements that could lead the least socially minded entrepreneurs to willingly subsidise the most socially minded entrepreneurs (thus safeguarding their sustainability) based on a thought experiment and on a model of entrepreneurs’ self-regulation.

To determine the first condition, I introduced a distinction between exogenous and endogenous solutions to the dilemma. The lesser the involvement of the actors concerned by its formulation, the more exogenous (or the less endogenous) the solution. In other words, it is easier to accept the negative consequences of an initiative if that initiative is one’s own (i.e., endogenous). On the other hand, exogenous initiatives – those which emanate from someone or somewhere else – can easily be rejected and resisted in that they are perceived as interference of an illegitimate kind. In this sense, they can easily become targets. The more exogenous the solution, the less likely it is to be accepted. A sustainable solution needs to be endogenous, one of my proposed solutions therefore consisting of an endogenous internalisation of externalities based on tax breaks. But there are others: for example, one could imagine a system where bonuses awarded to executives would be calculated collectively using a similar process.

The second condition is linked to the consequences of the conservation of money in the course of transactions, which might be alleviated, leading me to the radical suggestion that involves abandoning this notion – at least at the local level.

I do not suppose to have solved the problem of social enterprise’s sustainability, but more modestly I only sought to show that such arrangements, in spite of their counter-intuitive nature, are at least conceivable. My aim was simply to demonstrate the possibility of developing such institutional frameworks while leaving the ensuing matter of defining the concrete elements of the solution yet to be addressed. Like Nobel Prize winner Elinor Ostrom, who sought to define the conditions required for the efficient self-organisation of the collective management of public goods, I endeavoured to define the conditions for the self-organisation of a similar collective management of positive externalities by entrepreneurs…

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Ian Schneider on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Erwan Lamy is an associate professor of the information and operations management department at ESCP Business School, and an associate researcher at IDHES Cachan (CNRS, ENS Cachan). His work primarily uses social epistemology to define the organisational and institutional conditions for improving the reliability of knowledge production processes within organisations, in particular for innovative companies and research organisations. He is also conducting a philosophical reflection on management sciences.

Erwan Lamy is an associate professor of the information and operations management department at ESCP Business School, and an associate researcher at IDHES Cachan (CNRS, ENS Cachan). His work primarily uses social epistemology to define the organisational and institutional conditions for improving the reliability of knowledge production processes within organisations, in particular for innovative companies and research organisations. He is also conducting a philosophical reflection on management sciences.

I am afraid I couldn’t make head or tail of what this article was about.

I would love to learn more about your two conditions that you talk about above, especially about your radical suggestion for the second condition.