What is the essential task of management? To look after the short term in ways that not only protect, but even enhance medium and long-term prospects. For businesses, the COVID-19 crisis presents massive challenges to fulfilling this quest; it is difficult to pull off even in periods of growth. Previous downturns demonstrated how problematic it is to ride out, for any length of time, dramatic falloffs in sales, inventory problems, customers defaulting on debts, running out of cash, and delayed new products. Understandably, businesses focus on short-term survival and adaptation. Then begins the slow process of recovery. How are businesses responding this time? And what role will digital technologies play?

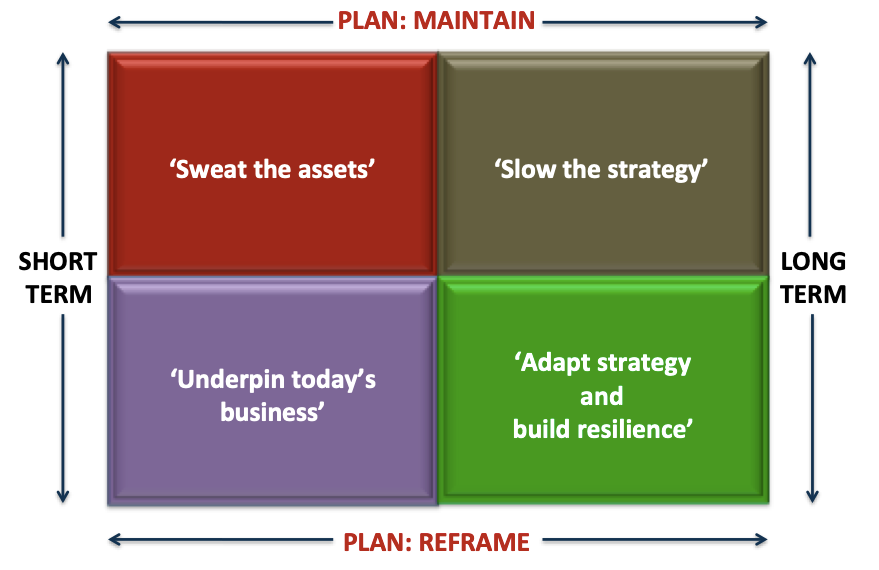

By August 2020, as part of the research for a new book Global Business: Strategy In Context (SB Publishing, forthcoming), we had surveyed and assessed how large international organisations across sectors were planning, over 2020-21, to recover business and leverage digital technologies. We compared the results to similar surveys during the 2000-2003 and 2008/9 economic downturns (see research note at the bottom). This produced some telling findings. I will organise these as four likely scenarios (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Business coronavirus responses – scenarios

Let’s look at each emerging scenario, and the take-up in 2020:

- Sweat the assets – Prolong the life of legacy processes and technology, and work staff harder to survive the crisis. Shelve IT investments, cut marketing and operational costs, make headcount reductions, outsource for cost savings. In 2020, some 30% of organisations were taking this approach.

- Underpin today’s business – Focus on the short-term business imperatives of keeping customers and finding new ones, while keeping the lid on costs. Expenditure limited to technology, marketing and operational improvements that support these goals. Keep headcount costs under control with more use of outsourced and part-time labour, and increased work automation. In 2020, we found some 35% were ‘underpinning today’s business’.

- Slow the strategy – As in previous downturns, change the timescale for delivering the strategy, accepting that it is directionally correct, and will be supported by adequate finance and resources. This time, assume that some adaptations to strategy will be needed both to get to recovery and after, due to an increasingly unpredictable business environment. Maintain planned technology investments, albeit at a slower pace, and strengthen business continuity plans. Some 20% of organisations were ’slowing the strategy’ during 2020.

- Adapt strategy and build resilience – Assuming a continuing strong financial operational and market set-up, take the opportunity to invest in process, technology and people to ride out the crisis, shift business strategy and gain competitive advantage on a five year horizon. Ensure resilience in supply chains, mode of operating, and accelerate use of automation and digital technologies. Some 15% of organisations were taking this approach so far in 2020.

The comparison with previous downturns is telling. In 2000-2003, 27% of organisations went for a hybrid short-term approach, 48% slowed the strategy, and 25% built infrastructure. During 2008/9 many more (52%) went for a hybrid short-term approach, reflecting a more severe financial crisis. Meanwhile 48% slowed the strategy, and none took a long-term reframing approach. However, as the 2008/9 downturn lengthened and deepened we found organisations that slowed the strategy moving to much greater prioritisation of short-term responses.

So what is different this time? Clearly this downturn is hitting harder, forcing businesses into more crisis-induced short-termism. Fewer businesses seem to be able to hold a steady line on strategy. But here, for 2020-21, there is also a seeming paradox. Many more organisations were making a short-term response (65%). However, many more were also adapting strategy and building resilience. There is a polarisation of responses. More short-termism, but also more long-termism as well. How do we explain this? There is a ‘dual track’ explanation. The short-termism reflects the more uncertain, dynamic business contexts, and systemic risks that have developed since previous downturns. Also the urgency, and depth of the slowdown imposed by a pandemic resulted in harsher shutdowns and more dramatic fall-offs in business globally. On the other hand, the organisations taking a more long-term approach were in stronger positions through entering the crisis in good shape, and/or were in ‘winner’ sectors (the most obvious example being technology companies). Interestingly, those opting to ‘slow the strategy’ this time (20%) did recognise that there would need to be adaptations to strategy during and coming out of the downturn, exhibiting again a strong sense of today’s uncertain dynamic global business environment.

We can also highlight two factors in 2020 that received no profile in the previous downturns. The first was a high concern for resilience, even where the executives did not feel in a good position to build this. Many began resolving to ensure that their organisations would become adaptive and more ready for uncertain events. In many ways this is a rather late realisation. For example, a 2014 Cranfield study ‘Roads To Resilience’ pointed out that resilient practices led to superior sustainable business value. Risk radar anticipated problems early, partly by seeing things in a different way. Diversified assets and resources provided flexibility to take opportunities and respond to averse events. Relationships and networks allowed risk information to flow freely throughout the organisation to prevent the “risk blindness” that afflicts many boards. Rapid response capability prevented escalation into a crisis or disaster, and facilitated recovery. The organisation could evaluate and learn from experiences, making requisite improvements in strategy, capabilities and processes. A resilient business, then, is one that can anticipate problems, adapt strategy, operate differently in changing circumstances, in ways that create sustained business value.

Since that 2014 study, the call for resilience has been reinforced by an acceleration in environmental connectedness, complexity and uncertainty – as showcased by the pandemic and economic crises of 2020-21. There is something else. For over a decade the advocacy of business digital transformation has been strong. The 2020-21 crises highlighted the need for, and will accelerate the adoption of digital technologies.

Not surprisingly, then, the executives we studied during 2020 raised this second, related factor of technology support for both survival and growth. The pandemic profiled virtual working, contact centres, logistics technologies and dependence on technology infrastructure. It also tested – positively – how these technologies could provide operational resilience. It is likely that the 2020-21 experience will change managerial mindsets once and for all on the need for operational resilience and technology support. For some time, managers have been utilising information and communications technologies. They have also been aware of multiple emerging digital technologies waiting to be exploited. The health and economic crises will be a catalyst for accelerating the take-up and integrated use of major technologies like social media, mobile, cloud, analytics, blockchain, AI, internet of things, digital fabrication and augmented reality.

However, this time we do not expect all organisations to come out of the crisis in the same way or at the same level of business health. Part of this is that different sectors will be more adversely affected and take longer to recover. Several studies suggest that, in the face of a muted global economic recovery it could take more than five years for the most affected sectors – for example arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation and food services, transport and warehousing, manufacturing, services generally – to return to pre-2020 profitability and growth. Even less affected sectors – for example – construction, retail, finance and insurance, utilities, wholesale trade, administrative and support services – could take to early 2023 to get to 2019-level contributions to GDP.

What do we expect businesses to do? In this crisis more organisations were taking emergency measures (sweat the assets). We anticipate them, if successful, to then take further action to ‘underpin today’s’ business’ in the economic recovery period. We expect these initial mid-2020 positions to evolve. If the crisis is prolonged, and just as in the 2008/9 downturn, organisations in the ‘slow the strategy’ mode will increasingly move to securing today’s performance. Those adapting strategy and building resilience will already have the capacity to look after current business health, while planning and building for the long term. Certainly, the businesses that come out of the crisis better are likely to be those who feel more capable of having long-term plans. But there might be some over-confidence here. An April 2020 McKinsey executive survey found 59% choosing ‘optimistic’ scenarios, with the most popular being where public health response is effective, but the virus recurs and economic policy interventions are only partially effective. This assumes a staggered U-shaped recovery. This was a likely scenario, but as we know from forecasting generally, there can be no guarantees. Could one assume, safely, that no further crises would hit during 2020-21? The evidence by August 2020 suggested otherwise. Perhaps a W-shaped, or even staggered W-shaped, recovery will occur, and how prepared for that will businesses be?

The great corporate solace in all this seemed to be the increasing faith in digital technologies to align with and support business posture. Even those sweating the assets were still buying more technology where they had no alternative, primarily for home and remote working, and automation of processes. The key here was to automate and digitise the existing operating model. Those looking to improve business performance went further and could be quite opportunistic, often accelerating previous planned investments (particularly in automation, analytics, cloud, and social media and customer-facing processes) in order to fulfil short-term business imperatives.

Amongst the ‘slow the strategy’ corporations, interestingly, while investment in other resources declined, technology investment has not slowed to the same extent, if at all, and in some cases has accelerated, and not just for the short term. The crisis seemed to act as a wake-up call, initiating a re-prioritisation of digital transformation plans. Meanwhile those adapting strategy were looking after the short term with stronger technology, while investing further in technology infrastructure and digital technologies to allow strategic flexibility and organisational resilience going forward.

The conclusion? The positives are that the technology so far invested in has held up, under severe pressure. Undoubtedly this will prompt further investments to build resilience for next time, but also to accelerate moves to becoming digital businesses, in order to compete with those already more advanced in the same sector. There is a caveat, however. In the recovery, organisations will emerge more technologised than ever before, but some will be much better placed competitively than others, perhaps irreversibly so, partly because of their technology policies before and during the crisis, and their good luck in being in the right sector at the right time. In this respect, the COVID-19 period may turn out as a significant turning point in the history of corporate digital transformation, exacerbating a pre-existing digital divide. This would see some organisations accelerating into superior sustainable business performance while the competitively disadvantaged rest would be limited to playing an endless game of catch-up. Future crises would only create a further shake-out of less resilient, under-technologised businesses.

| Research note |

|---|

| During May-August 2020 we sent an online survey to 600 large organisations in our proprietary LSE database. The database of 2,500 plus organisations was built over the 2010-2020 period through a series of business and technology-related research projects. The survey was designed to compare with previous surveys in the 2000-3 and 2008/9 recessionary periods. We gained 234 usable responses. Some qualifications. Firstly, these were executive expectations which would inevitably change with time and new events. Secondly, the sample was selective, rather than random, but designed to represent multiple sectors and leading economies. Thirdly, the respondents were not shown the scenarios. These were generated from the responses, and are the researcher’s interpretation. |

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by kate.sade on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Leslie Willcocks is a professor of technology, work and globalisation at LSE’s department of management. His forthcoming book is Global Business Strategy In Context. This can be pre-ordered from www.sbpublishing.org.

Leslie Willcocks is a professor of technology, work and globalisation at LSE’s department of management. His forthcoming book is Global Business Strategy In Context. This can be pre-ordered from www.sbpublishing.org.