An April 2020 press release read: “World Bank Predicts Sharpest Decline of Remittances in Recent History.” Except that this prediction due to COVID did not prove correct. In June 2020, the Dominican Republic received a 26 per cent larger amount in remittances – the money immigrants send home – than in June 2019. Honduras saw a 15% year-on-year increase that month, while El Salvador’s remittances rose 10%. Guatemala hit historic records in remittance flows in July and August 2020.

It is not just in Central America that remittances have rebounded after the initial COVID closures. Pakistan recorded a 37 per cent increase in remittances in June to August 2020 relative to the same period in 2019. The Philippines saw an 8 per cent increase in June-July 2020. Even Nepal, where the World Bank predicted a precipitous decline, had remittances at around the same level in 2019/20 as in 2018/19. Remittances inflows to Egypt, North Africa’s largest recipient, have also been countercyclical to the crisis, as Egyptian workers abroad increased one-off transfers to their families since May.

The financial reports of Western Union and MoneyGram — service providers which facilitate remittances — reveal a similar rebound in international payments in the third quarter of 2020 relative to 2019. Western Union reported a 6% increase in transactions in its third financial quarter compared to the same period last year, while MoneyGram reported a 10% international transactions growth between July and September.

For immigrants, supporting their families is the reason they left their homes in the first place. Forecasters failed to see that millions of migrant workers kept jobs in Europe and the United States that were deemed essential during the pandemic — in health care, agriculture, food production and processing. COVID also provided opportunities for new temporary jobs that were not picked up by local workers. Remittance flows have proven countercyclical, as they have in previous crises.

The numbers

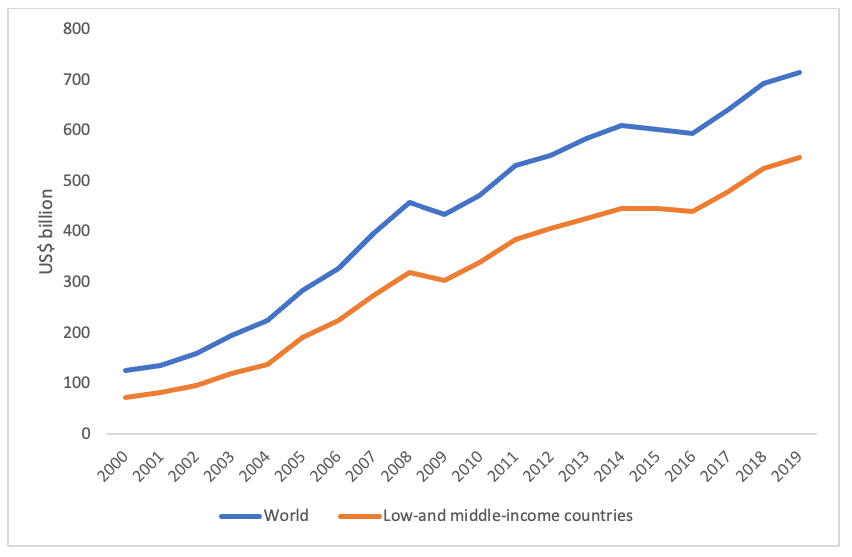

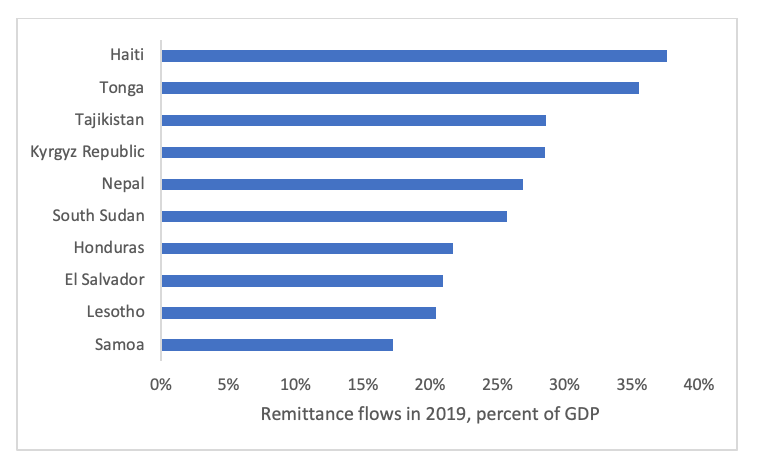

Worldwide, remittances reached $717 billion in 2019, of which $548 billion flowed to low and middle-income countries (figure 1). Some countries depend heavily on remittances, for example Haiti at 38 per cent of GDP; Tonga at 35 per cent; Tajikistan and Kyrgyz Republic at 29 per cent; Nepal at 27 per cent and South Sudan at 26 per cent (figure 2). A sharp decline in remittances would lead to a contraction of these economies, in addition to the economic woes due to their own COVID measures.

Figure 1. Remittance flows 2000-2019

Source: The World Bank, Remittance Inflows, October 2020

Figure 2. Top 10 countries in remittances as a percentage of GDP, 2019

Source: The World Bank, Remittance Inflows, October 2020; International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020; and authors’ calculations.

Change in remittances due to COVID

In April, the World Bank estimated that remittances would fall by 20 per cent in 2020. Six months later the forecast was corrected to a decline by 7 per cent in 2020, followed by a further drop of 7 per cent in 2021. The factors driving the decline in remittances include weak economic growth and employment levels in host countries and weak oil prices affecting migrants in Russia and the Middle East.

While some remittances were simply postponed in the spring and later restarted after the initial COVID wave, some migrants have returned to their home countries, suggesting that remittances may fall further in the future. The response to the crisis among a number of Middle East countries, including Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, has been to put pressure on countries like Bangladesh to repatriate their migrant workers. As another example, more than one hundred thousand Lao migrant workers have returned home from Thailand and Japan as a result of COVID.

The second pandemic wave

The strain on remittance flows in some regions may get worse with the rising second wave of COVID infections that has caused new constraints on business activity in France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom, as well as some large emerging economies like Russia. While forecasts have markedly improved since the start of the pandemic, they can worsen again in the coming months.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Robin Canfield on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Simeon Djankov is policy director of the Financial Markets Group at LSE and a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). He was deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. Prior to his cabinet appointment, Djankov was chief economist of the finance and private sector vice presidency of the World Bank. He is the founder of the World Bank’s Doing Business project. He is author of Inside the Euro Crisis: An Eyewitness Account (2014) and principal author of the World Development Report 2002. He is also co-editor of The Great Rebirth: Lessons from the Victory of Capitalism over Communism (2014).

Simeon Djankov is policy director of the Financial Markets Group at LSE and a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). He was deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. Prior to his cabinet appointment, Djankov was chief economist of the finance and private sector vice presidency of the World Bank. He is the founder of the World Bank’s Doing Business project. He is author of Inside the Euro Crisis: An Eyewitness Account (2014) and principal author of the World Development Report 2002. He is also co-editor of The Great Rebirth: Lessons from the Victory of Capitalism over Communism (2014).

Madi Sarsenbayev is a research fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. He is involved in work related to international finance, monetary policy, and political economy.

Madi Sarsenbayev is a research fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. He is involved in work related to international finance, monetary policy, and political economy.

Do we know why they did not fall as heavily as expected?