Cesar Revoredo-Giha and Adelina Gschwandtner analyse the data and find that in the case of organic meats, higher prices can explain the increase in sales, since quantities have been decreasing. For them, If the UK is interested in promoting the growth of the organic sector, it must develop its supply chain, simultaneously expanding demand and increasing supply.

There is an increasing interest in food production that is more environmentally friendly as shown in a report by the Assembly Citizens (Assembly Citizens, 2020), where chapter six speaks about the food we eat and how we use the land.

Organic production fits that environmental interest because food is produced using practices that cycle resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity. Moreover, the use of certain pesticides and fertilizers in the farming process is restricted. In terms of organic livestock production, in comparison with conventional production, this is characterised by access to outside (outdoor) space, lower stocking density, no growth promoters, longer withdrawal periods and on-farm feed production.

Despite the aforementioned characteristics, the organic sector as a proportion of the conventional sector remains quite small. Moreover, it contrasts with the frequently shown upbeat news regarding the sector such as “UK Organic Food and Drink sales boom during lockdown” (The Guardian, 2020). In this article, we examine organic foods focusing on the situation of organic meats.

Situation of organic meats

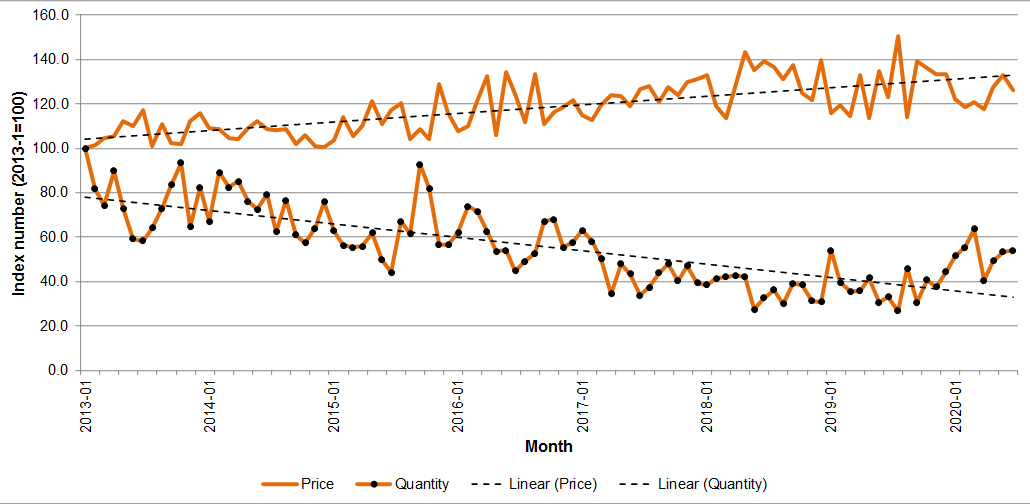

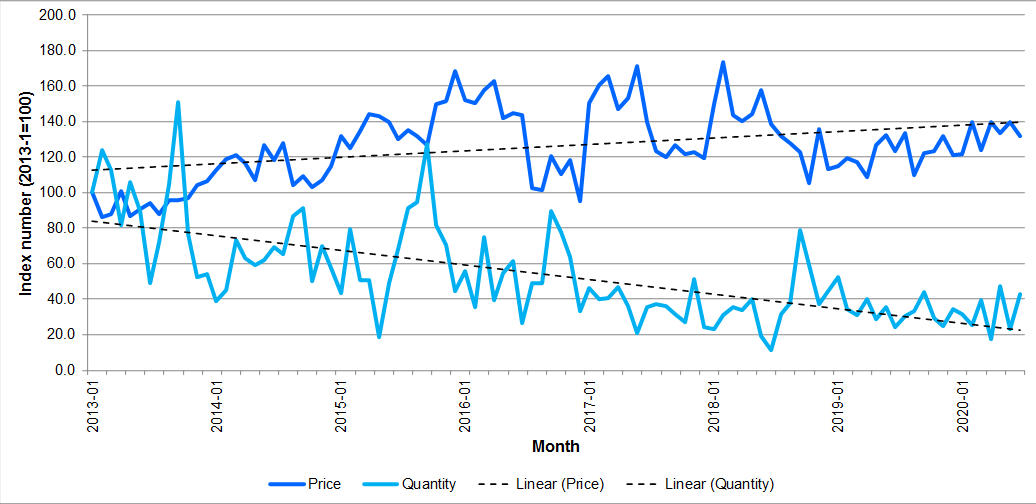

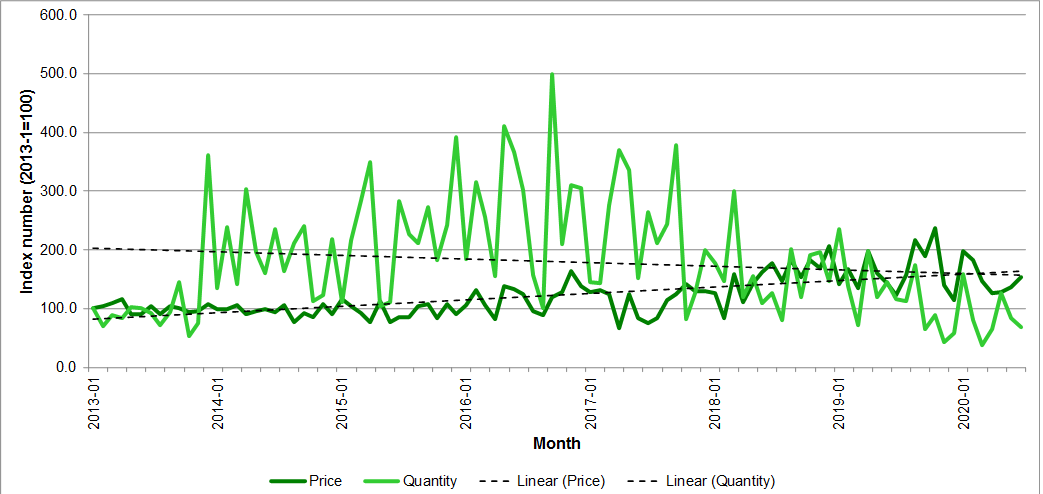

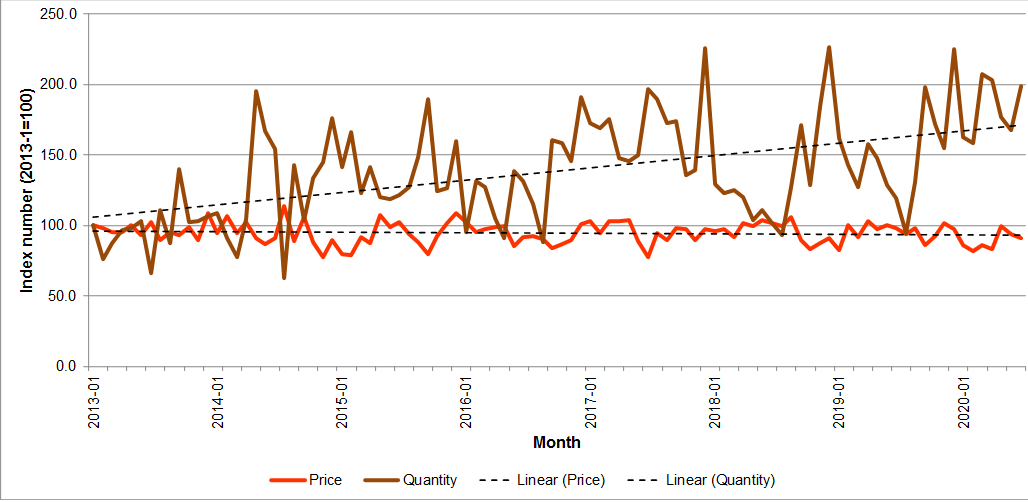

Figures 1 to 4 present the evolution of price and quantity indices from 2013 to 2020 for beef, lamb, pork and poultry. For beef, lamb and pork situations are quite similar — characterised by trends that show an increase in price and decrease in quantities purchased. In contrast, for poultry, prices remained stable, whilst quantities increased.

Figure 1. UK prices and quantities indices of organic beef

Source: Own elaboration based on Kantar Worldpanel data.

In the case of beef, the annualised average monthly growth rate of prices for the entire period was 3.3%, whilst the same rate for beef quantities was -10.5%. For lamb, the growth rate of prices was, like with beef, 3.3%, but quantities decreased more significantly (by 14.2%). For pork, prices grew by 8.8% but quantities only decreased by 4.1%. Organic poultry prices grew during the period by 0.4% and quantities by 6.9%.

Figure 2. UK prices and quantities indices of organic lamb

Source: Own elaboration based on Kantar Worldpanel data.

Figure 3. UK – prices and quantities indices of organic pork

Source: Own elaboration based on Kantar Worldpanel data.

Figure 4: UK – prices and quantities indices of organic poultry

Source: Own elaboration based on Kantar Worldpanel data.

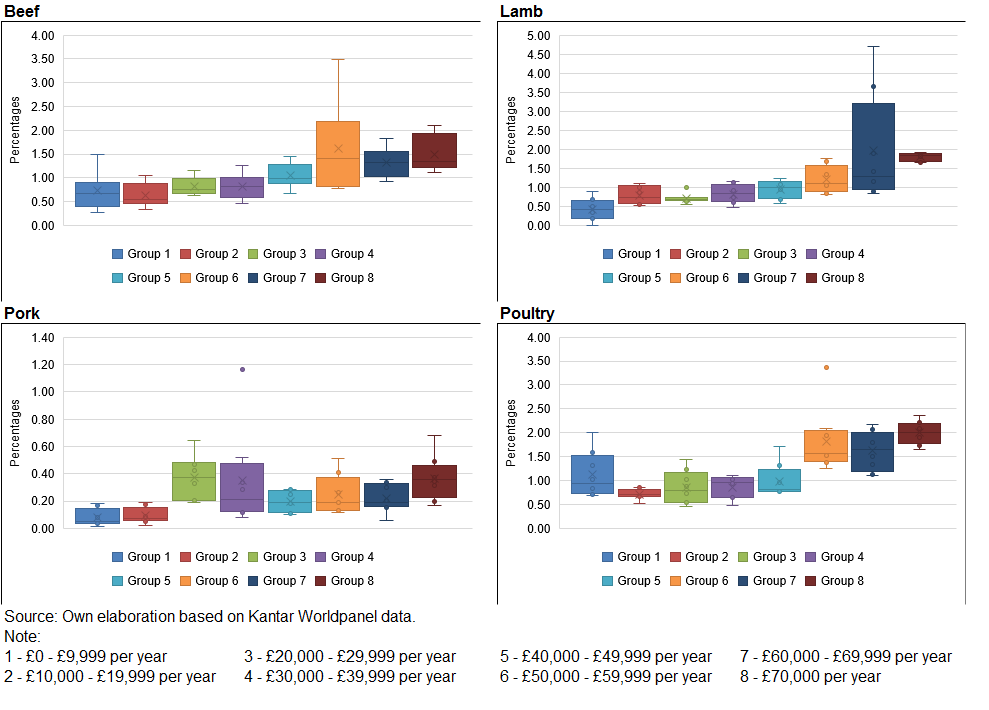

Whilst trends in prices and quantities are important, market shares are also relevant, because they indicate the degree of penetration of organic products in households. Figure 5 shows boxplots by meat and income group. Two aspects are clear from the graphs: first, they show that all meats except for pork have penetrations (i.e., shares) that increase with income groups. The second aspect is that all the shares are below 5%.

Figure 5. UK – market penetration of organic meats by income group

What to do?

Contradicting some of the news about the progress of the organic sector, the data show that in the case of the organic meat market, any increase in the value of sales was mostly due to rising prices rather than consumer uptake (quantity). As shown, this is not something that changes if the data are analysed by income groups. The increase in price and the relatively low range and availability of organic food products in UK supermarkets are potential reasons for the observed decrease in the consumed quantity of organic meats (e.g., Gschwandtner 2018).

In our view, the data show the need—if there is an interest in promoting the growth of the organic sector—to develop its supply chain, simultaneously expanding the demand and increasing the supply of the sector. Interestingly, this matches the recent published plan for the organic sector for the EU- 27 (i.e., EC, 2021).

The ‘Action Plan for the development of the organic sector: on the way to 2030’ is an important part for the European Green Deal, which stands at the centre of the European Commission’s policy agenda towards a sustainable and climate-neutral Europe. Under that agenda, organic farming is supposed to deliver those environmental objectives through its sustainable use of natural resources and processes.

The Action Plan (EC, 2021), which was unveiled on March 25, is divided into three axes, namely: (1) organic food/products for all: stimulate demand – ensure consumer trust; (2) on the way to 2030: stimulating conversion and reinforcing the entire value chain; and (3) leading by example: improving the contribution of organic farming to sustainability.

The actual measures proposed by the EC to address the above points encompass encouraging organic farming and its logo, promoting the use of organic products in canteens and as part of school schemes, and facilitate the contribution of the private sector, which are a necessary combination of push and pull. If the high prices are due to high average costs, then expanding the production level should take advantage of scale economies but this is only possible if there is a steadily increasing demand.

An additional cost for the organic sector is to demonstrate that it has followed all the required protocols, and of course there are all the issues related to information asymmetry and avoiding fraud (particularly if the sector expands). Therefore, the measures to foster the sector will have be accompanied by actions to prevent food fraud and improve traceability as in the case of the EC plan.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Andreas Haslinger on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy