The pandemic makes it important for economists to work together with epidemiologists, who must work out the trade-offs between economic and health outcomes. Costas Milas assesses the impact of lockdown and other social distancing restrictions on the UK economy, allowing for the impact of standard economic and financial ‘controls’. COVID-19 restrictions are factored in through the University of Oxford’s stringency index (featuring school and workplace closures, among other restrictions).

In January 2020, economists polled by The Financial Times predicted that the UK economy would grow by approximately 1.4% in 2020. This prediction could hardly have been further off the mark (the economy contracted by 9.8% in 2020) due to the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. This very forecasting failure brings to mind Daniel Defoe’s “A Journal of the Plague Year”. Maybe we should learn from the 1665 plague of London, where Defoe noted that all predictors, astrologers, fortune tellers and “cunning men” did disappear from the streets. It is tempting to think they all realised their professions had nothing useful or optimistic to report at the time.

The COVID-19 pandemic should make economists rethink their (quantitative) models. With this in mind, I attempted to assess, in new research, the impact of lockdown and other social distancing restrictions on the UK economy allowing also for the impact of standard economic and financial ‘controls’. In my research, UK growth benefits from lower economic policy uncertainty and lower volatility in financial markets. In addition, the more money circulates in the economy, the more the economy expands.

The link between money and economic activity depends heavily on the definition of money. I use ‘Divisia’ money because this very measure of money (that weights component assets of money in accordance with their usefulness in making transactions) predicts UK economic activity quite well. At the same time, ‘Divisia’ money works in empirical models better than the Central Bank’s traditional policy rate and more so when the policy rate is ‘stuck’ at a zero level (the Bank of England’s interest rate is currently at 0.1%).

To capture COVID-19 restrictions, I rely on the stringency index produced by the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford. The index is the average of nine sub-indices (namely school closures, workplace closures, cancelation of public events, restrictions on gatherings size, closure of public transport, stay at home requirements, restrictions on internal movement, restrictions on international travel, and public information campaigns); each sub-index taking a value between 0 and 100. The higher the index, the stricter the rules.

The quantitative analysis allows me to infer GDP movements under the assumption that no social distancing or lockdown restrictions are put in place. Clearly, this is an illustrative scenario rather than a realistic one. With the pandemic spreading rapidly and the UK death toll rising to unthinkable levels (a total in excess of 128,000 to date), social distancing and lockdown restrictions became a one-way street. The empirical model returns an average annual GDP growth of -9.1% since the pandemic (between March 2020 and January 2021 in my model) compared to 0.6% in the counterfactual scenario where no restrictions are imposed. Therefore, restrictions reduced, on average, annual UK growth by 9.7 percentage points compared to the scenario of no government action.

At the other extreme, the model returns an average annual GDP growth of -11.0% in the counterfactual case where the economy remains in strict lockdown (that is, the one we witnessed between late March 2020 and during April 2020) up until January 2021. Again, this is just an illustrative (and unrealistic) scenario because had this been the case, most of the UK population would have, one way or another, followed the example of Dominic Cummings in breaking lockdown rules. Therefore, a strict and continuous lockdown during the pandemic would have, according to my research, reduced annual UK GDP growth by a further 1.9 percentage points compared to the impact of the imposed restrictions. The impact on the economy of the continuous strict lockdown scenario is slightly worse than what actual lockdown policies deliver which arguably suggests that the economy adjusts and gets on during lockdown restrictions.

Under what circumstances are stringency measures lifted?

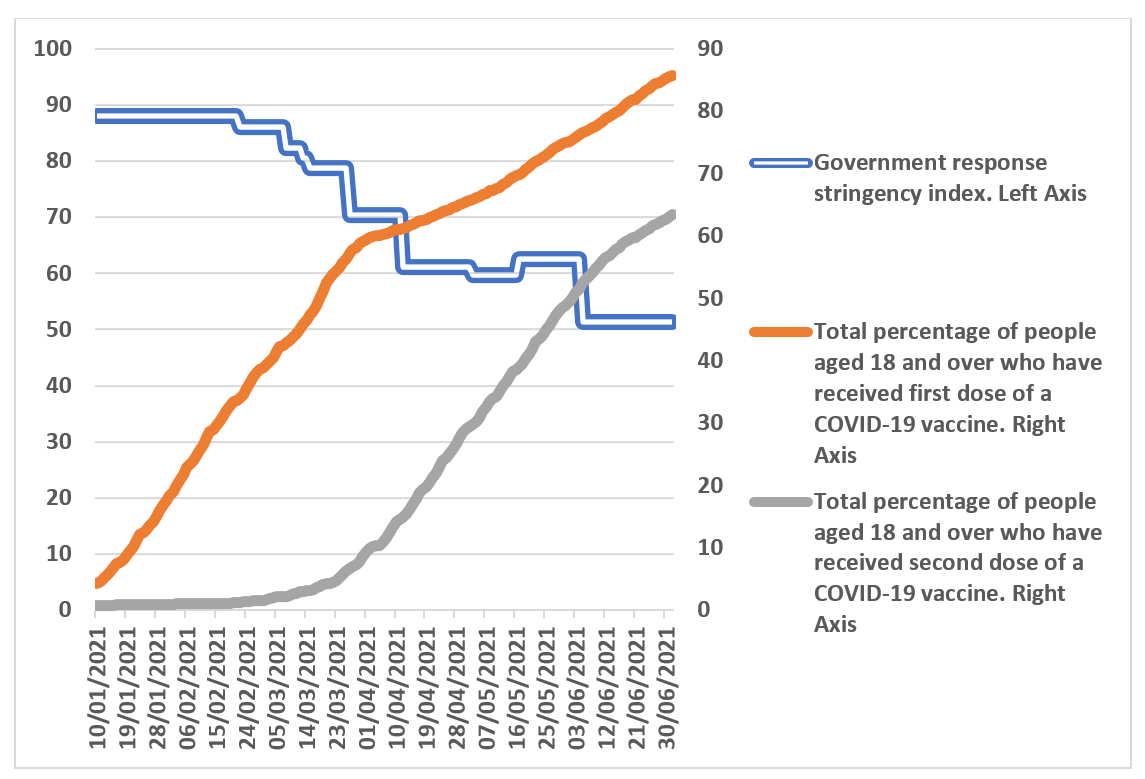

Stringency measures are lifted and, consequently, the economy powers ahead when COVID-19 infection cases drop (or when COVID-19 related admissions to hospital drop) and, at the same time, when the uptake of the vaccination programme proceeds fast. From Figure 1, 85.7% (63.4%) of UK’s adult population had received, by early July 2021, a first dose (second dose) of a COVID-19 vaccine.

My research finds that the pace at which lockdown restrictions have been eased since January 2021 appears more responsive to the proportion of the UK’s population who had been fully inoculated than the number of people who had received a single dose of vaccine. This finding is consistent with the government’s decision to delay lockdown easing (initially planned for June 21st 2021) by four weeks on the grounds that COVID-19 infections and hospital admissions were on the rise and additional full vaccination uptake is needed to enhance protection against the Delta coronavirus variant (first detected in India) in particular.

Figure 1. Government response stringency index and vaccination uptake in the UK, January to June 2021

Notes: Government response stringency index from the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT). Vaccination uptake from the UK Coronavirus Dashboard.

Despite the relaxation of lockdown restrictions in 2021, considerable uncertainty remains with reference to the UK’s future economic prospects. With Brexit now signed-off, the UK economy is also facing a new relationship with the EU. According to the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee and in comparison to a frictionless arrangement, UK trade is expected to be around 10.5% lower in the long run under the new agreement, and GDP around 3.25% lower (the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee judges that most of the impact on GDP will come through over the next three years). But when it comes to non-economic factors, it makes sense to expect that UK growth in 2021 (and perhaps beyond) will depend, among others, on the speed of the vaccination programme; how often and fast the virus mutates; and, consequently, the ability of existing vaccines (or new ones) to protect against further mutations. There is a good reason why the World Health Organization decided to name variants by using the Greek alphabet which has no less than 24 letters…

Whatever the future holds, the pandemic should force us to rethink not only our models but also potential collaborators. Given the adverse and devastating effects of the pandemic, it makes sense for economists to consider the issue of working together with epidemiologists not least because dealing with the pandemic involves, and will continue to involve, trade-offs between economic and health outcomes.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Grant Ritchie on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

There was a definite reduction in orders within manufacturing at the start but as people came back to work it picked up again.

The manufacturing sector is now being hampered by high material prices and excessive power costs.