The COVID-19 pandemic and Brexit have been felt keenly by the UK’s food and drink industry. The two events have caused shocks in supply and demand that have affected the industry’s segments differently. Cesar Revoredo-Giha looks at the evolution of the index of production published by the Office for National Statistics and outlines the issues that might affect the industry in the months ahead.

The start of the lockdown in March 2020 marked the beginning of an unprecedented period of instability for the UK food supply chain, characterised by demand and supply side shocks and economic policy uncertainty.

On the demand side, the sudden increase in purchases of grocery products due to panic buying and other reasons (see previous blog post) stressed not just supermarkets but their entire supply chains. Although there was uncertainty about how the sector was going to cope—due to its reliance on just-in-time logistics, which keeps relatively low levels of inventories and works in a very synchronised way—it certainly did cope, showing amazing capacity of organisation as well as cooperation between the different stages of the supply chain.

The demand for groceries was not the only domestic demand shock that the food industry had to face. The lockdown brought the closure of the hospitality sector, which represented an important contraction in demand. This affected particularly the wholesale market, but the impact was felt by all industries delivering to the hospitality segment of food services.

The third affected demand source was the external market, and the Brexit process has been in great measure the reason behind it (see previous blog post). The uncertainty brought by it was fully achieved at the end of the Brexit transition (31 December 2020).

On the supply side, the effects of the pandemic were felt hand in hand with the constraints introduced by Brexit (through the end of free labour movement from the EU), which generated shortages and inflexibilities in the supply of labour (e.g., HGV drivers, butchers, and seasonal fruit and vegetable pickers). These factors seem to be here to stay, as the observed increase in wages most probably will not be able to close the gap in the short and medium term between the demand and supply of labour (and neither will visa policies) because of the need of skilled labour, not just labour.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has published the evolution of the index of production up to August 2021, which allows us to look at how the food sector has been faring. This does not reflect recent events such as the increase in gas prices and its impact on energy costs, and by-products such as CO2 but it helps visualise what sectors are struggling, and which ones are recovering.

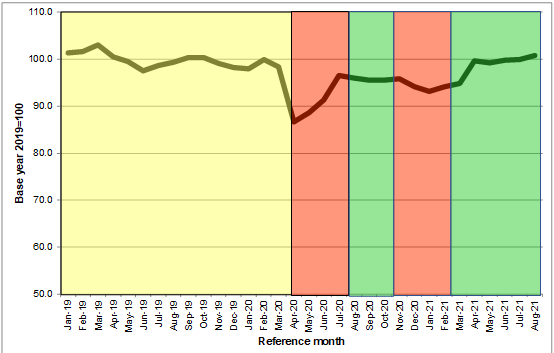

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the seasonally adjusted food and drink production index and Figure 2 disaggregates the index by sector. They contain five transparent panels, which were constructed considering different periods of lockdown (red) and relaxation (green) and the period pre-pandemic (from January 2019 to March 2020) in yellow. The periods were selected based on the timeline of UK coronavirus lockdowns published by the Institute of Government.

Figure 1 shows the sharp decrease in the sector’s production in April 2020, quick recovery by July 2020, stagnation until January 2021 and a growing trend since then, indicating recovery. Note that the value achieved by April 2021 is already comparable to pre-COVID values. Whilst several factors may explain the recovery trend, the slow re-emergence of the hospitality sector is a key factor. In August 2021, the ‘Accommodation and Food Services’ sector was 3% above the January-February 2020 value.

Figure 1. Evolution of the index of food and drink production

Source: Office for National Statistics

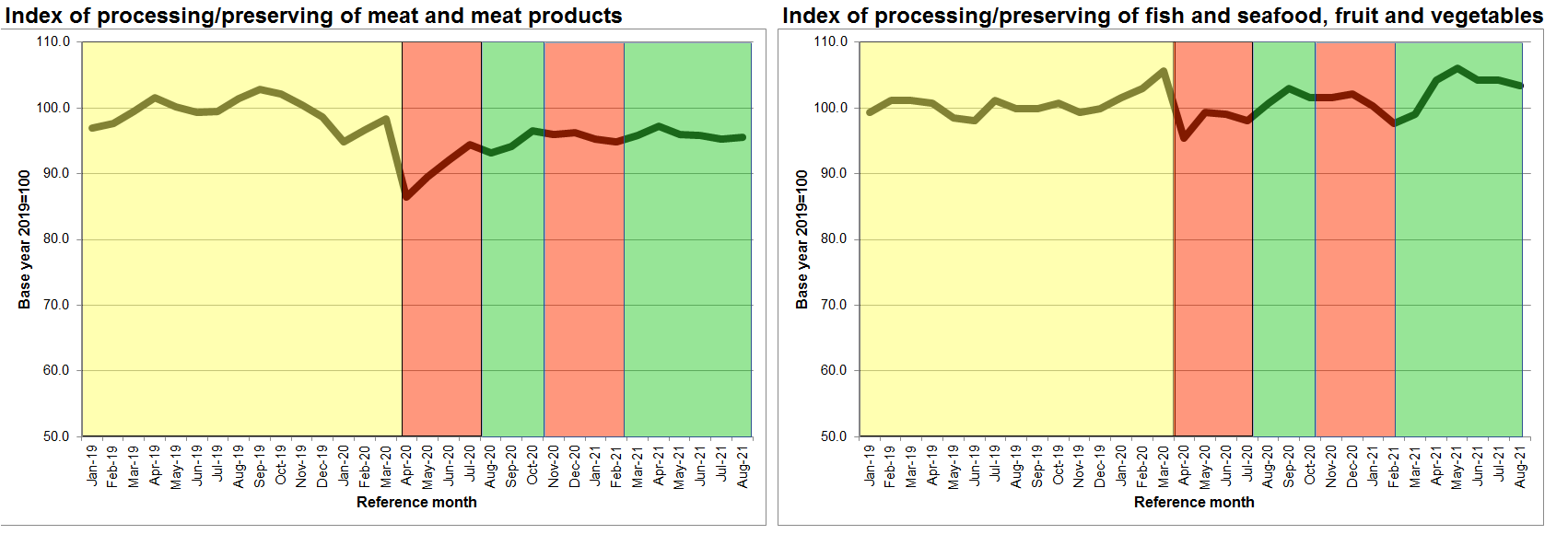

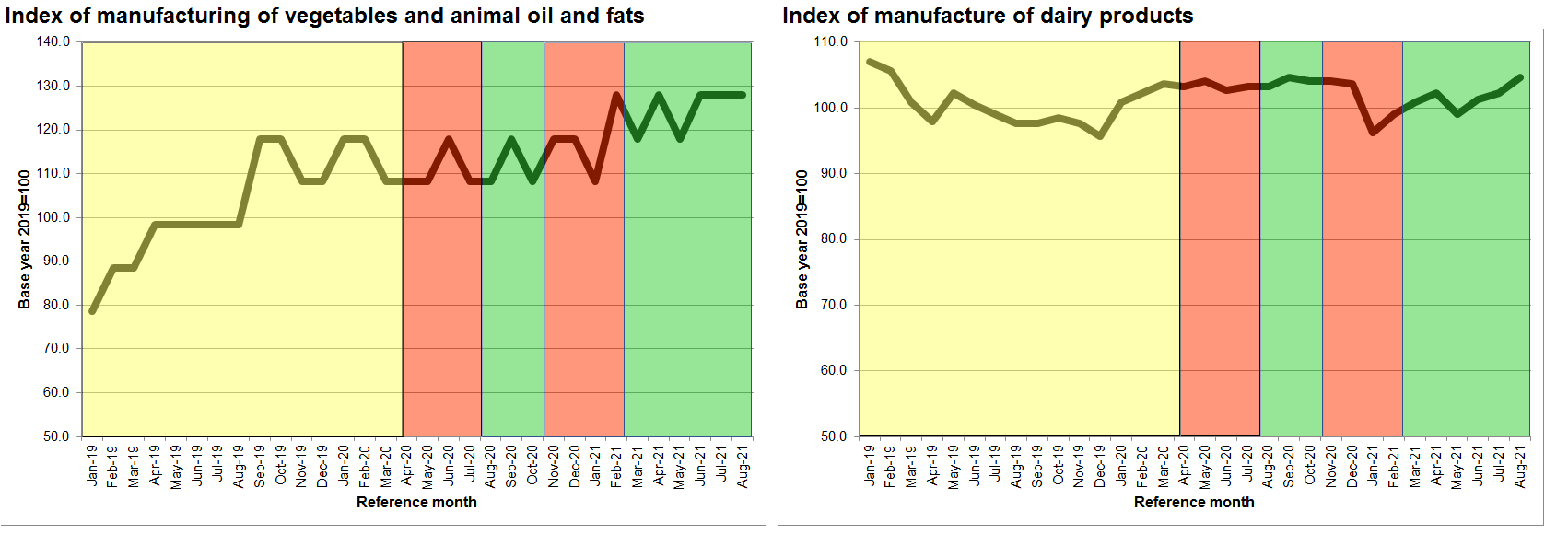

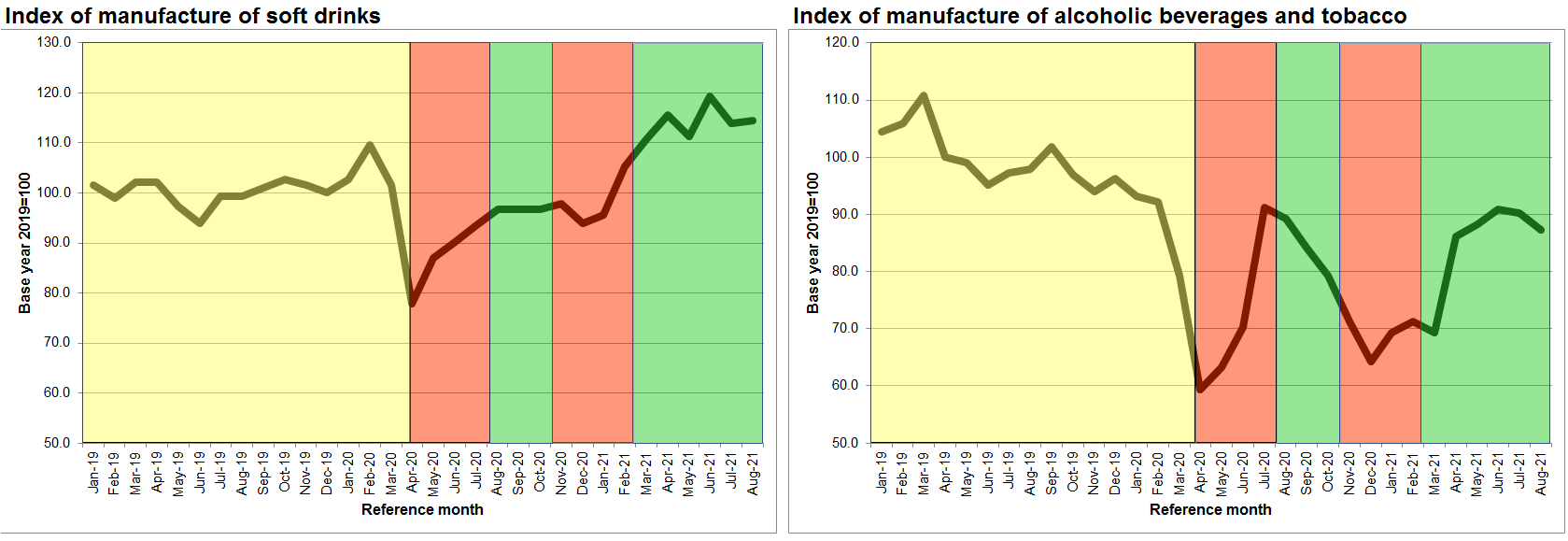

As shown in Figure 2, there is a diversity of trajectories amongst the different segments comprising the food and drink sector. Almost all the industries were affected by the first lockdown at the end of March 2020.

Five trajectories can be identified in Figure 2. The most common one shows the well-known ‘V shape’ just after March 2020, followed by a slow recovery. This is the case in the following segments: processing of meat products, processing of fish, fruit and vegetables, manufacture of bakery and farinaceous products, and manufacture of soft drinks. Despite the increasing trends after the lockdown shock, there are differences in terms of how far the recovery reached in each industry. Thus, the processing of meat and meat products still shows levels below the pre-pandemic period, whilst the manufacture of bakery and farinaceous products as well as soft drinks shows in August 2021 levels markedly above those of 2019.

Figure 2. Situation by industry segment

Source: Office for National Statistics

The second trajectory is the manufacturing of vegetables and animal oil and fats, which shows an increasing trend during the entire period (2019-2021), and in contrast with other industries, it is difficult to identify any effects of the pandemic.

The third trajectory is represented by the manufacturing of grain mill products, which shows a decreasing trend since the pre-pandemic period. According to IbisWorld, the industry’s performance is due to weak domestic demand, volatile wheat harvests and prices over the past five years.

The fourth trajectory, depicted by dairy manufacturing, shows a relatively stable pattern with levels in 2020 and 2021 very similar to those of 2019. This is very interesting because the dairy sector delivers part of its output to both: the hospitality sector and the EU market, which means that the sector was able to shift some of its output to the domestic retail sector.

The final trajectory, of alcoholic beverages and tobacco manufacturing, shows a marked decrease in April 2020, sharp recovery by July 2020 and another decrease by December 2020. This is not odd as the sector demand is closely associated with the evolution of the hospitality sector.

The road ahead

Although the statistics up to August 2021 seem to show that the food and drink sectors are following paths towards recovery, they are still surrounded by a thick mist of uncertainty, particularly regarding external demand, availability, and cost of skilled labour, as well as energy prices. These factors, of course, may affect the observed trends in the months to come.

The situation with the EU, our main trade partner, is still evolving and unresolved due to the situation regarding Northern Ireland. Although the EU has presented its latest proposals simplifying the movement of goods from Great Britain to Northern Ireland, it is inflexible in its opposition to removing the European Court of Justice’s role as arbiter of protocol disputes between the EU and UK, which the UK government is keen to do.

Labour shortages need to be solved in the short term to ensure the full recovery of the food and drink sector. Moreover, it is imperative to plan how to improve the situation in the long term to avoid chronic shortages in the industry. This will require a realistic policy aimed at closing the labour gap observed in the industry either through a flexible stable immigration policy or investing in acquiring the required skills domestically.

Higher energy prices due to the impressive rise in wholesale gas prices are the latest in a string of issues affecting the food and drink industry. The full implications are still to be seen, and although the sector may not use energy as intensively as other sectors (e.g., steel production), energy is an important input.

Increases in wages and energy prices may necessarily bring higher consumer prices, something that the retail sector is anticipating.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Tina Witherspoon on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.