Policymakers are increasingly focusing on wellbeing as a policy goal, leaning on wellbeing measures to aid their work. Paul Dolan writes that the existing frameworks fail to properly account for the fundamental mechanism that determines our wellbeing: what we attend to. Together with colleagues Kate Laffan and Laura Kudrna, he created the Welleye framework, which shows the role of attention in linking the objective circumstances of people’s lives to how they spend their time – and ultimately to how they feel.

Policymakers are belatedly showing interest in wellbeing measures, and there are several existing frameworks to guide them. Typically, they have focused on income or objective goods, such as health status and social capital. More recently, the frameworks have been broadened to include reports of how satisfied people are with their lives, and how they feel day-to-day. But they all fail to properly account for the fundamental mechanism that determines our wellbeing: what we attend to. Our attention can be directed towards what we are doing, who we are with, and the thoughts that occupy our minds. These stimuli will be shaped by the circumstances of our lives and our preferences.

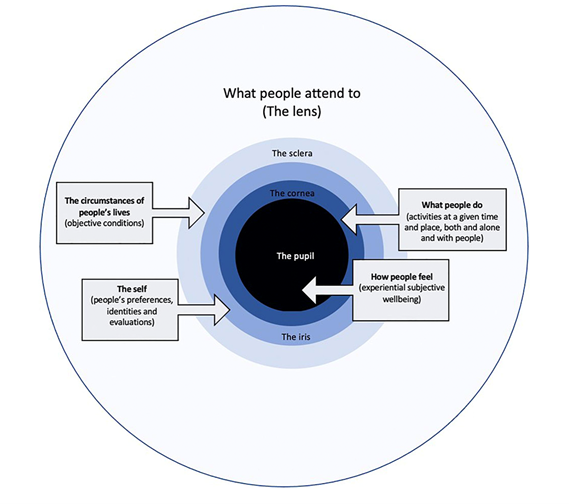

The “Welleye” is a new framework that I designed with Dr Kate Laffan from LSE’s Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science (PBS) and Dr Laura Kudrna from the University of Birmingham. The Welleye shows the role of attention in linking the objective circumstances of people’s lives to how they spend their time – and ultimately to how they feel. The Welleye model accounts for how the same stimulus – money, access to healthcare, food, jobs – can have a very different effect on how people feel, depending on the attention allocated to it. For example, how a person’s income affects them will depend on to whom they compare themself to and how they spend their time – and on the attention they pay to these comparisons and experiences.

In brief, the outer eye (the Sclera) represents the circumstances of people’s lives, such as their age, gender, health status, where they live or if they are married. The inner eye represents aspects of people’s “subjective selves”. The cornea captures preferences, identities, and evaluations (including assessments of life satisfaction). The iris consists of the stimuli that people attend to in their daily lives. The pupil represents people’s feelings day-to-day over the course of their lives. The sclera, cornea, iris, and pupil are all understood to have an important role to play in sight. Equally, the relationship between individuals’ circumstances (the sclera), their preferences (the cornea), and what they attend to (the iris) need to be optimised to achieve the ideal aperture of focus (the pupil).

Figure 1. The Welleye framework

The policy implications of the Welleye framework

The Welleye can assist policymakers to better understand the determinants of wellbeing and how to promote it. Through the lens of the Welleye, policymakers should be concerned with people’s circumstances, selves, and activities only insofar as they affect how people feel. The Welleye can help to embed wellbeing into policymaking in various ways.

For example, it can help policymakers to explore the objective conditions of people’s lives that best explain what they pay attention to and how they feel. It can be used to highlight important interactions between circumstances that act to promote or impede people from feeling well. It can also help to identify activities that are important determinants of wellbeing that policy has traditionally ignored, such as sleep, relationships, and technology use. Further, it can show how those with very low wellbeing spend their time and the circumstances of their lives with a view to tailoring any policy interventions for maximal effect. It can highlight groups for whom wellbeing largely unresponsive to traditional interventions. It can alert policymakers to adaptation and feed into the design of interventions that account for this process e.g., by focussing on ruminations and intrusive thoughts. Finally, it can show how wider funding structures and multi-sectoral approaches could be applied in a joined-up way to interactively tackle problems across policy silos, such as obesity.

How the Welleye can be used in organisations

When it comes to employee wellbeing, the Welleye can help organisations focus their efforts. After all, workers who are happy and well have been shown to perform better and be more creative. These causal effects are of individual, organisational and societal benefit.

As an example, in designing a rewards scheme, employers can use the Welleye to work out how a scheme would affect what people attend to and how they feel. A pay rise could draw attention to the extrinsic benefits of work and reduce intrinsic motivation to achieve, and the attention-seeking nature of a lump sum annual bonus may be different to that of more regular but smaller bonuses. Bonuses or rewards that are made public will likely be more attention-seeking than those made privately with important consequences for how the recipients feel. And sometimes in ways that are not predicted: public recognition of achievements can be welfare-reducing because they make everyone bar those being recognised feel a whole lot worse.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on The Welleye: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding and Promoting Wellbeing, with Kate Laffan and Laura Kudrna, in Frontiers in Psychology.

- The post expresses the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Caleb George on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Well done guys this is great stuff! I do love a framework. I can (and hopefully will) use this in my work. Thank you.

A neat way of outlining a complex set of considerations. I liked the practical example – are you interested with partnering with organisations to develop or test the model? Get in touch if so

Well done Paul, Kate and Laura! I will use this myself!

Very interesting perspective…Congratulations for your work! I wonder if this same framework could be used in the case of people suffering from a chronic illness. What do you thing?

Brilliant framework! Congratulations Paul, Kate, and Laura!

I can’t help noticing that the iris and the cornea should be inverted in the image as they don’t match with the notes.