The adoption of green labels by financial institutions is not regulated. Some issuers use the green label for non-green bonds, leading to sub-optimal outcomes for those who invest in these securities. This means that investors systematically under-allocate money to inherently green bonds and over-allocate it to inherently non-green ones. Karim Henide overviews a promising initiative by Austrian electricity provider Verbund, which sets what he considers a gold standard for green debt architecture.

There was a time when adverts were witty. Now a relic of a bygone age, one such string of ads was produced by the darling of Danish beer drinkers, Carlsberg. The “If Carlsberg did” adverts sought to zone-in on relatable experiences, such as supermarket shopping, addressing the inherent inconveniences and inefficiencies of everyday life with the Carlsberg-loyal at the centre of the skits. For the most part, the improvements were not singular innovations but a curation of multiple ideas, which together formed a situational panacea. In the same vein, transplanting ideas from the sustainable finance market, Verbund, the Austrian power major predominantly owned by the Republic of Austria, has envisioned a panacea for the green bond market which sets a gold standard for green debt architecture.

Green use of proceeds bonds are “a standard recourse-to-the-issuer debt obligation […] proceeds […] tracked by the issuer […] linked to the issuer’s lending and investment operations for eligible Green Projects”, as defined by ICMA. Effectively, proceeds are earmarked for allocation to demonstrably environmentally additive economic activities. The green bond market, which we’ll use as a proxy for all ‘use of proceeds’ impact finance labels, provides a toolbox that can be used to effect a targeted, positive impact and support credible economic transitions.

The market is a private sector-dominated solution that has partially bypassed due government intervention to support an economic transition and mitigate the ‘climate free-rider problem’, amongst other ineffaceable environmental and social issues.

Currently, the adoption of green labels by financial institutions can be virtually costless and is not regulated. This perceived regulatory oversight deficit is problematic for investors looking to allocate money to rational value-maximising corporate issuers. The incumbent environment, reminiscent of George Akerlof’s “Market for Lemons” analogy in illustrating informational asymmetry (when one party has access to information that the other does not), forms incentives for issuers of inherently non-green debt to label their bonds as green. Bond-labelling, an ex ante declaration of purported ‘greenness’, occurs under a setting of informational asymmetry, giving rise to the adverse selection problem, whereby parties with an informational advantage (e.g. sellers of non-green bonds, which they label as ‘green’) can benefit from outcomes that are sub-optimal to their counterparties (e.g. purchasers of non-green bonds labelled as ‘green’). Adverse selection, in our case, means that investors systematically under-allocate money to inherently green bonds and over-allocate it to inherently non-green bonds. The prospect of additional demand from investors seeking to allocate to green bonds is attractive to the rational value-maximising issuer of inherently non-green bonds, who recognises the opportunity to benefit from a ‘greenium’, or pricing premium, helping to drive down firm cost of capital and mechanically increase (shareholder) value.

The predicament of the resulting allocative inefficiency is double-pronged. For one, it erodes investor confidence in the market segment and constrains the potential growth of the global pool of sustainable development capital. Similarly, issuers of inherently green bonds may be disincentivised from upholding a higher degree of green ambition, given the market’s under-compensation of their efforts, relative to inherently non-green issuers labelling their bonds as ‘green’. The result is a constraint on the market’s potential growth, its potential to effect a positive impact and a reduction in the quality of realised outcomes.

The market has evolved to partially resolve some of the underlying structural issues, to self-regulate and to address the perceived deficit in surrounding regulatory infrastructure. External reviews, analysis, and assurance from third parties on bonds’ proposed greenness and on the merit of their post-issuance impact reporting have helped to improve transparency. Whilst survey evidence indicates that these services are relied upon by investors more than their own in-house analysis, there are issues of consistency amongst reviewers and potential conflicts of interest. Problematically, external reviewers are currently not supervised.

Green bond issuers can equivocate liability (indeed, we have not observed an issuer being taken to court over the purported greenness of their issuance). Bolstering market confidence requires regulation and enforcement to provide investors with a credible route for recourse. One parallel innovation has been the development of sustainability-linked bonds, which embed a ‘trigger event’ resulting in a structural impact, such as coupon step-ups (bond interest rate increases), introducing skin-in-the-game and a dynamic that is conducive to effective market self-regulation. These instruments can be calibrated through their underlying ‘sustainability performance targets’ (‘SPTs’), to ensure that issuers, rather than just bonds’ proceeds, are aligned to longer-term science-based targets. Alone, however, the sustainability-linker mechanism fails to ensure that bond proceeds are directly allocated to sustainable ends. These instruments are often issued by corporations in the harder-to-abate sectors, where issuers lack sufficient capacity to issue in the green bond market and require short-term capital flexibility to support their long-term transition ambitions. More generally, it should be noted, many bond issuers and investors view linker mechanisms within ‘fixed’ income as an oxymoronic concept, defeating the purpose of known and consistent nominal cashflows, which are characteristics that are conducive of effective financial planning and valuation.

On 1 April 2021, Austrian electricity provider Verbund came to market with EUR 500 million in 20-year ‘green and sustainability-linked notes’, a synthesis of a green and sustainability-linked bond. The specific use of proceeds outline four EU Taxonomy-aligned ‘Eligible Green Projects’ (Weinviertel line, Salzburg line, Reschenpass project, Töging-Jettenbach), which include plans to support renewable wind and hydropower energy capacity expansion, outcomes which the coupon step-up events are linked to. Verbund have combined the ringfence-like design of green bonds, whereby proceeds are hypothecated for specific project use, with the linker mechanism. In an ideal world, this architecture would be the gold standard for the issuance of green debt instruments, intended to credibly tether debt financing to a science-aligned transition path.

With respect to mass adoption, the determination of sufficiently ambitious, comparable and localised sustainability performance targets, as well as trigger events, requires consideration amongst other obstacles, such as the vulnerabilities of self-reporting on key performance indicators. Such an approach would also naturally only suit a voluntary standard, to prevent alienating issuers on the margins from engaging. Whilst there may be some aversion from issuers and investors who would prefer to avoid uncertainty and potentially higher volatility, green sustainability-linkers are a powerful instrument which should be promoted in the funding toolbox to align project-level proceeds and entity-level transitions with science, capitalising on corporate issuers’ inherent incentive to maximise firm value.

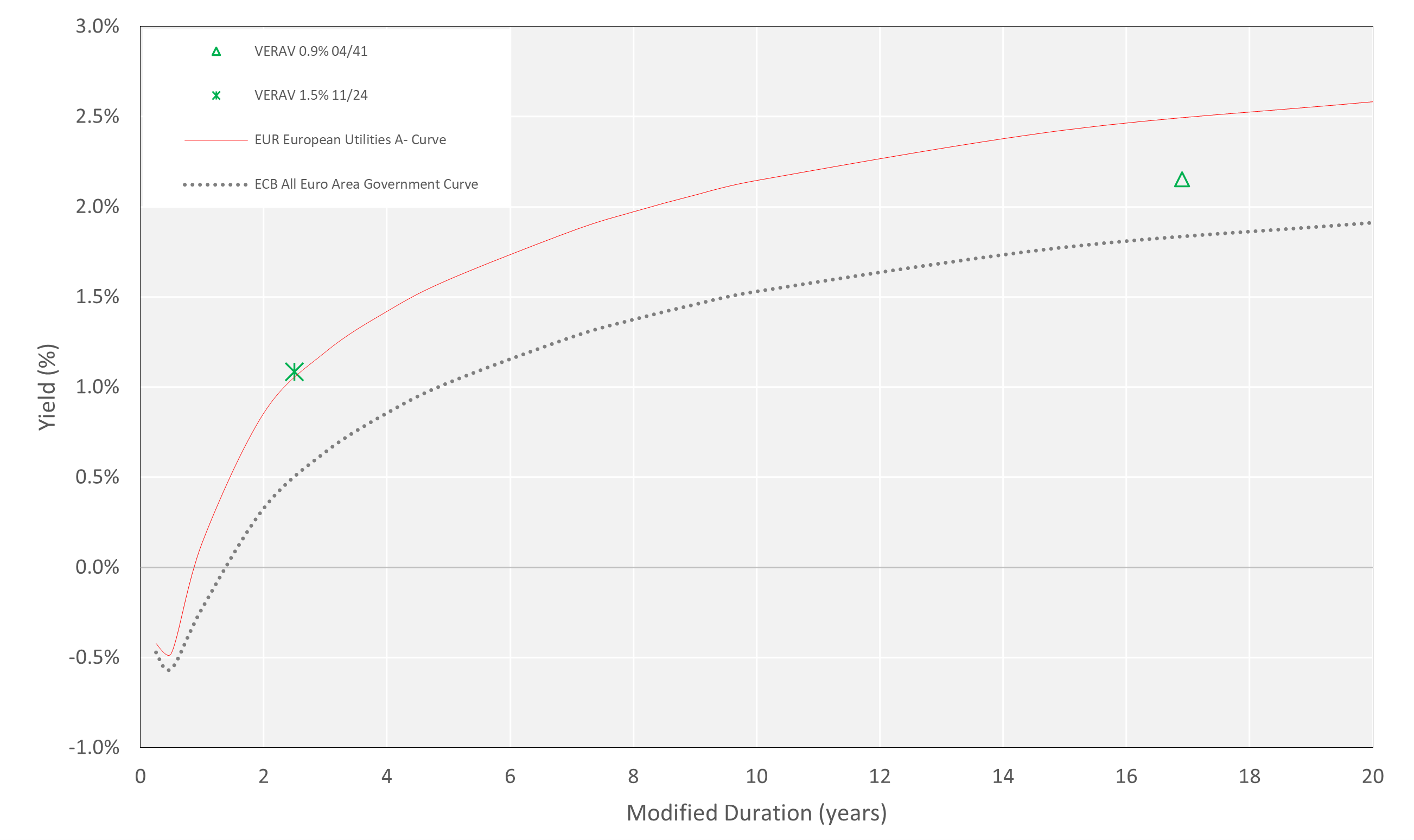

Whilst Verbund does not have an established yield curve, it can be observed that the Verbund 2041 ‘green and sustainability-linked’ instrument trades notably tighter relative to the Euro curve than peers and further inside the peer curve than the previous 2024 green bond issuance.

Figure 1. Verbund 2041 trades much tighter relative to the Euro curve than peers and the previous 2024 green bond issuance

Source: Bloomberg, author

Author’s disclaimer: I am not in any way linked to Verbund (no direct or indirect conflicts of interest for myself or my family).

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on ideas articulated in Green lemons: overcoming adverse selection in the green bond market, Transnational Corporations, Volume 28, Issue 3, Dec 2021, p. 35-63.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Sarah Pflug under a Burst licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy