Exploring how social ventures build and orchestrate beneficial social network arrangements over time as the social venture grows, and what drives these changes, is essential, especially in societies where collectivism prevails and networks serve as a substitute for weak formal institutions, often creating social obligations. In their research in Kenya, Christian Busch and Harry Barkema collected longitudinal data for over a decade and identified four novel mechanisms that allowed successful ventures to adjust their networks as they scaled.

Social networks are crucial for social enterprises, as they can help mobilise resources to tackle societal issues. However, although the literature has provided important insights into the types of networks that are required to develop and grow (“scale”) social impact, it tends to assume networks are developed for specific projects, existing already, or that organisations have the leverage to develop networks easily, usually because they are large/reputed already. Yet, social enterprises tend to require changes in their networks based on different resource requirements, challenges, and projects over time. Thus, exploring how social ventures build and manage (“orchestrate”) beneficial social network arrangements over time as the social venture grows, and what drives these changes, is essential.

This exploration is particularly important in the Sub-Saharan African emerging economy context, where prior research has argued collectivistic tendencies prevail (i.e., prioritising the group over the self), and where networks serve as a substitute for weak formal institutions, while often creating social obligations as well. Given the lack of systematic insight into how social enterprises scale using social networks in this context, in our new paper we asked, “How and why do social enterprises in the Sub-Saharan African emerging economy context successfully orchestrate their networks as they scale?”

Research setting: Kenya

Our research setting was Kenya, a Sub-Saharan African country characterised by collectivist tendencies and relatively weak formal institutions that has been at the forefront of innovative inclusive business models in emerging economies. Given our limited collective knowledge of how social ventures orchestrate their networks as they scale in this context, we used an inductive theory-building approach with a multiple-case-study design. We collected longitudinal data for over a decade—from April 2011 to September 2021—through interviews, emails, Skype calls, archival data such as internal growth plans, and observations, for example, at local “show farms” that educated farmers on fertiliser effects.

Our final sample comprised six social agri-ventures, which engaged low-income residents, particularly farmers. All ventures provided farmers with key supplies such as fertiliser and aimed to help them increase their income. All ventures faced the business model challenge of poor customers, requiring the enterprise to look for a broad range of potential funders early on, such as international development organisations, NGOs, and grant-based collaborations, while generating their own revenue, by selling their outputs to farmers and supermarkets. Other challenges included seasonality, low profit margins, and restrictions on scale due to regulations; for example, honey or fertiliser certifications were less developed in Kenya, limiting export opportunities and increasing local competition, reducing prices.

Network orchestration

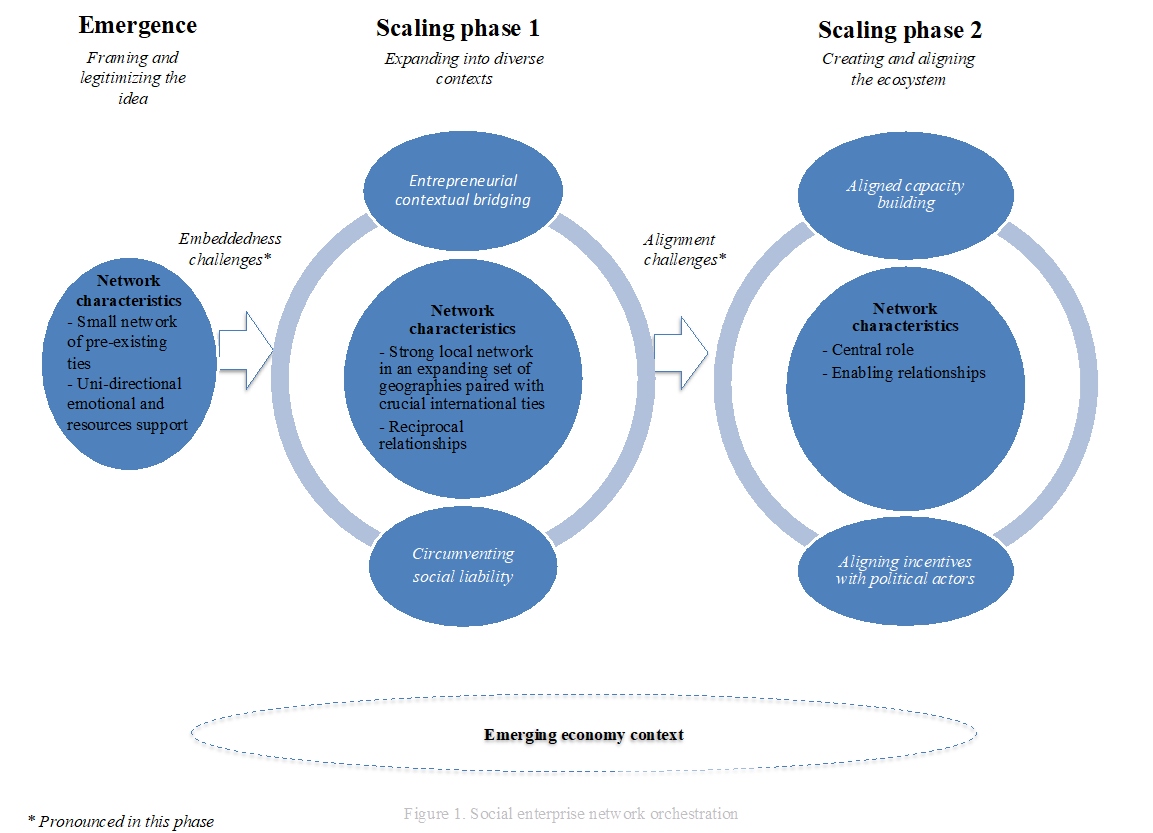

Our findings show how and why orchestrating social ties as a social enterprise scales is associated with success or failure. Two scaling phases, capturing strategic actions and network changes, emerged from our data, which we labelled “scaling phase 1” and “scaling phase 2.” Each phase showed common characteristics and challenges across ventures and helped explain why social ventures had to adjust their networks as they scaled (see Figure 1). Whereas scaling phase 1 network issues tended to be related to embeddedness challenges (i.e., being sufficiently but not too embedded in their respective local context while aiming to expand), scaling phase 2 network issues tended to be about ecosystem creation and alignment issues (i.e., building capacity of beneficiaries (i.e., farmers) conjointly with productive stakeholders such as international funders, and aligning with the objectives of government officials, who were of particular relevance in this context).

We identified four novel mechanisms that allowed successful ventures to adjust their networks as they scaled. First, entrepreneurial contextual bridging focused on transferring new meanings and practices to a context in a locally sensitive way while establishing legitimacy and credibility. Given major disparities across Kenya, such as tribal separations, successful ventures mediated between different groups and catered to the local languages of customers and local partners. They managed to convince locals of their legitimacy and recruited them into their network, for example, by having local representatives and partners make frequent public commitments in front of local villagers.

A second mechanism that we identified was circumventing social liability, which was about productively bypassing structural embeddedness constraints. This mechanism was important for dis-embedding from the local context when scaling up operations while keeping local legitimacy. For example, by involving effective family members in the organisation, based on merit, while creating opportunities for ineffective family members outside the venture, avoiding nepotism. A third mechanism that we identified was aligned capacity building, i.e., motivating partners to participate in coordinated efforts toward developing and strengthening the skills and resources of the focal beneficiaries. For example, successful ventures often supported the creation of new markets, e.g., by facilitating deals with crowdsourcing platforms that funded their customers (farmers). A fourth mechanism that emerged from our data was aligning incentives with political actors; i.e., engaging public officers in ways that harmonised with their objectives, for example, related to Kenya’s “vision 2030”.

Figure 1. Social enterprise network orchestration

Understanding sustainable entrepreneurial interventions and solutions in resource-constrained contexts

This research contributes to a deeper understanding of how and why social enterprises in the Sub-Saharan emerging economy context orchestrate networks as their ventures scale and require different resources over time. Capturing the social ventures’ network dynamics over time contributes to our understanding of how and why agentic network actions can help realise success as ventures scale in this context, and how design and orchestration failures can be circumvented via effective network orchestration. This has important implications for our understanding of sustainable entrepreneurial interventions and solutions in resource-constrained contexts by explaining how stakeholders’ interests can be aligned over time to “keep things together” and to enact effective ecosystems that outlive funders. For example, companies often fail to develop strong relationships with low-income communities, and insights from our study might help these companies develop more inclusive engagement strategies via approaches such as making public commitments in front of local community members.

Managing the “dark side” of social networks

Our study also contributes to understanding how to manage the “dark side” of social networks, for instance, expectations of family, friends, and politicians who do not meaningfully contribute to the venture. Given that the legitimacy of social enterprises in collectivistic settings tends to be based on achieving social objectives and being locally embedded, instead of using simple decoupling mechanisms such as cutting ties, the successful enterprises in our study decoupled these social ties from the social enterprise while providing value to them.

In sum, we provide new insights into how and why successful social enterprises develop and align networks in an emerging economy context over time, which improves our collective understanding of how agentic network actions can help overcome structural constraints as ventures scale in this context.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Align or perish: Social enterprise network orchestration in Sub- Saharan Africa, Journal of Business Venturing. The paper was awarded a Best Paper Award at the Academy of Management Annual Meeting.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Ninara, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Christian Busch & Harry Barkema’s article provides insights into how and why successful social enterprises develop and align networks in an emerging economy context over time.

I agree with the authors that social enterprises must align themselves with the right networks to succeed.

However, I think the authors could have provided more examples of successful African social enterprises that have done this.

Additionally, I would have liked more discussion on how social enterprises can identify the right networks to align themselves with.

Overall, I found the article insightful and helpful in understanding the importance of network alignment for social enterprises.