As UK inflation, currently at 9.4% and heading for 13%, is much higher than the official inflation target of 2%, Liz Truss is accusing the BoE of having been too slow to increase interest rates. Costas Milas argues that, 25 years since the Bank of England was given operational independence, it makes sense to revisit the issue of the bank’s mandate and look at things that can get better, as long as changes do not compromise the bank’s independence.

Liz Truss, the frontrunner to become Tory leader and the next prime minister, is keen to review the way monetary policy is conducted by the Bank of England (BoE). The reason is that UK inflation, currently at 9.4% and heading for 13%, is much higher than the official inflation target of 2%. Liz Truss is accusing the BoE of having been too slow to increase interest rates to deal with rising inflation. Let’s look at this issue in more detail.

The BoE was given operational independence in 1997 (by Gordon Brown, then chancellor of the exchequer) with the aim of targeting a 2.5% inflation based on the RPIX measure (retail-price index excluding mortgage interest payments). Since 2004, the BoE targets a 2% inflation based on the CPI measure of inflation. In more detail, the bank’s mandate is to deliver price stability – low inflation – and, subject to that, to support the government’s economic objectives including those for growth and employment. Price stability is defined by the government’s inflation target of 2%. The remit recognises the role of price stability in achieving economic stability more generally, and in providing the right conditions for sustainable growth in output and employment. In other words, although the BoE targets a 2% inflation, it also takes into account whether output growth is strong or weak. That is, when inflation is above (below) the 2% target, but GDP growth is weak (strong) the bank has the flexibility not to raise (lower) interest rates immediately.

Notice also that the BoE target is symmetrical: the bank views inflation above the 2% target as equally “bad” as inflation below the 2% target. If the target is missed by more than 1 percentage point on either side – i.e. if the annual rate of CPI inflation is more than 3% or less than 1% – the governor of the bank must write an open letter to the chancellor explaining the reasons why inflation has increased or fallen to such an extent and what the bank proposes to do to ensure inflation comes back to the target. Notice that the governor of the BoE is required to send a further letter after three months, if inflation remains more than one percentage point above or below the target.

Between January 2004 (when CPI inflation became the officially targeted measure) and June 2022, average CPI inflation has been 2.3%; so the Bank has managed to keep CPI inflation close to the 2% target. A reasonable performance given the 2008-2009 financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and now the Ukraine war. That said, inflation started going up, well in excess of the 2% target, from mid-2021 onwards, so it makes sense to argue that the BoE has been rather slow in responding to rising inflation.

So what things can change in the conduct of monetary policy if Liz Truss becomes prime minister? Before answering this, it is important to recognise that the existing inflation target of 2% does not mean that inflation will be held at this rate constantly. That would be neither possible nor desirable. Because monetary policy operates with a time lag of about two years, the BoE cannot change interest rates on day x and affect inflation on day x+1. It takes about two years to affect inflation. In any case, even if we wanted to hit the 2% target all the time, interest rates would need to be changing all the time, and by large amounts, causing unnecessary uncertainty and volatility in the economy. Even then it would not be possible to keep inflation at 2% in each and every month. Instead, the bank’s aim is to set interest rates so that inflation can be brought back to target within a reasonable time period (two years as I noticed above) without creating economic instability.

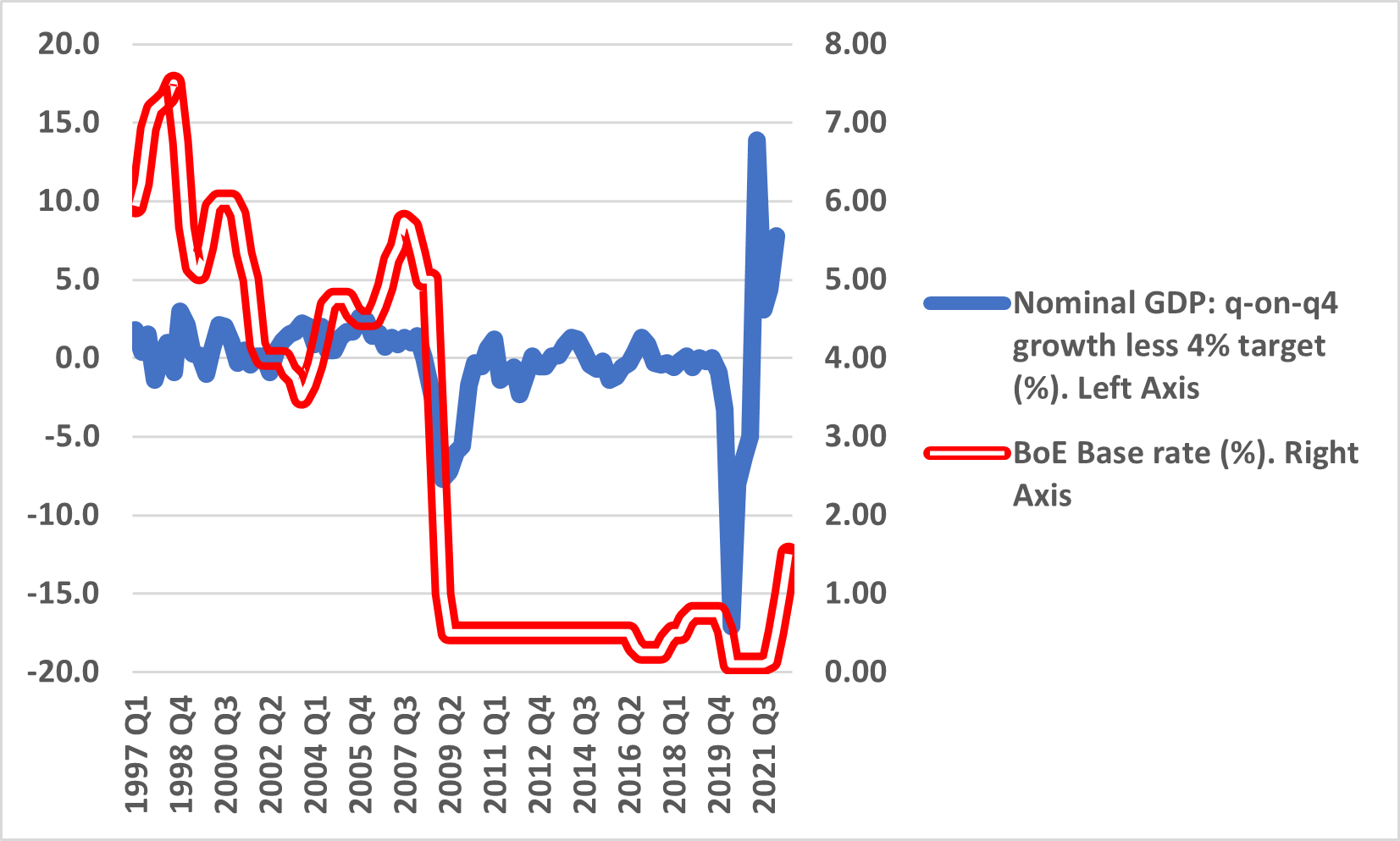

One alternative is to target nominal GDP growth (broadly speaking, real GDP growth plus inflation) at (say) 4%, that is, real GDP growth of 2% (the historical average from 1997 onwards) plus an inflation rate of 2% (the historical average from 1997 onwards). The problem here is that politicians and the public understand a 2% inflation target. A target on nominal GDP growth based on two components will be much more difficult to explain and deal with not least because we might end up with a situation of one component (e.g. growth) falling and another component (e.g. inflation) rising as it happens today. Interestingly, however, the correlation between deviations of nominal GDP growth from a possible 4% target (i.e. nominal GDP growth less the 4% target) and the BoE policy interest rate is 0.25 (see Chart 1). Although correlation does not necessarily imply causality, a possible implication of this chart is the following: had nominal GDP growth been targeted, it is more likely than not that interest rates would have moved not that differently from what actually happened over the last 25 years!!!

Figure 1. Deviations of nominal GDP growth from a possible 4% target and the BoE policy interest rate

Source: Nominal GDP growth here. BoE policy interest rate here.

Assuming that the existing CPI inflation target of 2% remains in place, there are other ways of dealing with the bank’s potential “failure” to hit the target. For instance, the BoE governor could be asked to write a letter if the target is missed by (say) 0.5 percentage points either way and then send a further letter after two months (rather than three) if inflation remains more than 0.5 percentage points above or below the target. In other words, the government could “force” the bank’s monetary policy committee (MPC) to respond more often than otherwise, by trying to keep inflation within a narrower band of between 1.5% and 2.5% rather than within the wider band of between 1% and 3%.

There are other things that can also be considered. For instance, rather than having five monetary policy committee (MPC) members from the BoE and 4 external MPC members deciding on interest rates, we could have four MPC members from the bank and five external MPC members or “rotate” to have five MPC members from the bank in one decision meeting (on interest rates), followed by five external MPC members in the following meeting. This would reduce the so-called “groupthink”, which quite often exists among the bank’s MPC members.

Liz Truss is not telling us what she has in mind. This is problematic. She has promised tax cuts from “day one” (immediately after 5 September) largely through extra borrowing. Notice that the BoE is currently planning to start selling UK government bonds (proceed with “quantitative tightening”, that is) before the end of September. The very selling of debt by the BoE and simultaneously by the government will push long-term interest rates much higher. In fact, borrowing might turn out to be even more expensive if financial markets take the view that Liz Truss and her ideas of “rewriting” monetary policy is a direct threat to the BoE’s independence. In other words, even higher interest rates (as a result of financial markets viewing BoE’s independence at threat) risk making a looming recession even worse. Quite frankly, the new prime minister (whether Liz Truss or Rishi Sunak) and BoE governor Andrew Bailey need to sit down and work together to counteract the adverse consequences of the looming recession.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Christopher Bill on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

The problem is inflation hasn’t been measured correctly for decades.

Want proof ? A house I used to own went up 417% in 22 years.

When most prices go up 10% there is an outcry that something must be done.

However, despite housing being one of most peoples major expenses if house prices go up 10% in a year many people think it is time to celebrate and think about a new car and a holiday.

A question I have been wanting to ask an economist for a long time.

If everything in the shops was free would people be better off?

I suspect that after a while, rent/mortgages would just take up most peoples wages.

The UK is an importer. With such a weak currency, everything is more expensive. Don’t forget natural gas and oil are all quoted in USD. Raising the rate is going to make everyone’s money more valuable