To avoid excessively high interest rates, with their impact on financial stability, some central banks desire to use more macroprudential policies in their policy formulations. Nicholas Apergis, Ahmet F. Aysan, and Yassine Bakkar analyse lender-targeted macroprudential policy instruments and borrower-targeted ones and describe their effects during economic upturns and downturns.

In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, regulators have shifted their attention to the macroprudential policies to reduce systemic risks and to ensure financial stability. It is yet another high time to think about the macroprudential policies, when interest rate hikes to limit inflation raise concerns for financial stability, as customers and firms are ever more in debt. The Bank of Japan fears raising interest rates to stabilise its currency. A prolonged period of low interest rate environment since 1980s has generated many zombie firms, resulting in potentially zombie banks. Even a small interest rate hike may reveal the known secret in Japan.

In the US, there are fears that raising interest rates to contain inflation may lead to a prolonged recession. Europe is not different, while fighting against inflation and fearing irreversible recession amidst an energy crisis and elevated geopolitical risks. Hence, once again, macroprudential policies emerge as a viable alternative to interest rate policy, which might deliver in controlling inflation, but harm financial stability, while exacerbating any recessionary concerns. In our recent paper (Apergis, Aysan and Bakkar, 2022), we offer insights on how macroprudential policies work and what type of macroprudential policies work better in upturns and downturns to systemic risk arising from intra-financial system vulnerabilities.

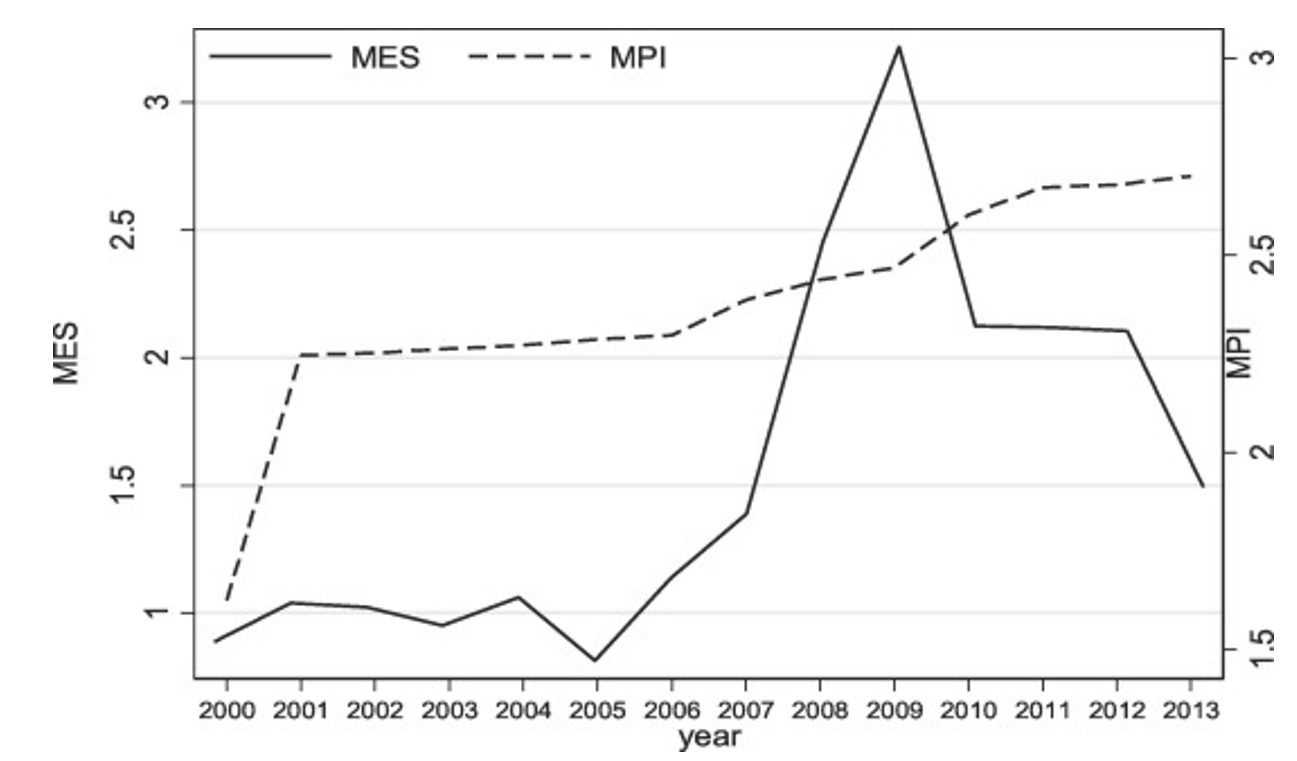

After the financial crisis, macroprudential policy tools have gained prominence. There is greater appreciation for their potential value in limiting spillovers between banks and limiting the accumulation of risks to systemic stability. These tools also reduce the negative consequences of financial volatility by mitigating excessive procyclicality. Nonetheless, despite widespread adoption of macroprudential regulatory policies to achieve financial stability goals, understanding these ex-ante policies and their efficacy remains a work in progress. In fact, this post-fact analyses of so-called academic life provide an invaluable asset to design new macroeconomic policies for the future, while contemplating the usual tradeoff between price stability, financial stability, and growth. Figure 1 illustrates our point. The figure plots, at the aggregated level, the relationship between macroprudential policies and bank systemic risk over the 2000‒2013 period. The figure illustrates that the number of macroprudential policies kept a steady increase since 2001. That is, the existence of macroprudential instruments was present even before the global financial crisis. The figure shows a negative relation between macroprudential policies and systemic risk after the 2008 global financial crisis, which may show the efficacy of macroprudential policies in reducing instability.

Figure 1. Evolution of the relationship between macroprudential policy and financial stability

Source: the macroprudential policy is an index constructed by Cerutti et al. (2017). Description: the figure showAdd Modules the relationship between the aggregate systemic risk arising from intra-financial system vulnerabilities (MES) and the aggregate macroprudential policy index (MPI) during the pre- and post- global financial crisis periods in the 25 major advanced OECD economies. The figure also indicates a negative relation between different macroprudential policies and bank systemic risk.

Detangling the potential trade-offs between the different macroprudential policies: lender-targeted instruments vis-à-vis borrower-targeted instruments, as well as their substitutability and complementarity with respect to the financial stability objective are of most interest of policymakers. Central banks frequently control both types of macroprudential instruments. A novel focus consists of highlighting the actual policy tradeoffs for central banks in adopting and implementing certain macroprudential policies with respect to other, for example: loan-to-value ratio cap vs. countercyclical capital buffers. In our recent work, we raise this question and investigate the effects of macroprudential policies in a cross-panel data set for listed OECD banks prior to the Basel III accords, as well as the complementarity versus substitutability of different macroprudential instruments in achieving the ultimate regulatory goal of enhancing financial stability, by reducing bank systemic risk and procyclicality.

The distinction between lender-targeted and borrower-targeted macroprudential policies has received little attention in the literature. This distinction, however, is critical for central bankers. Lender-targeted macroprudential policies are more indirect policies that affect the incentive sets offered by banks to borrowers. Due to the limited number of banks and the already stringent regulations imposed on them, lender-targeted macroprudential policies are easier to implement. Given the lack of data on bank customers, enforcing borrower-targeted macroprudential policies may take longer and be more difficult. Furthermore, governments prefer not to impose financial constraints on borrowers due to electoral concerns. As a result, it is necessary to examine the separate effectiveness of lender-targeted or borrower- targeted macroprudential policies, as well as their complementary effects on financial stability.

Such analysis was conducted for a sample of listed banks headquartered in the 25 major advanced OECD economies from 2000 to 2013. The database of macroprudential measures was created based on the updated Cerutti et al. (2017) dataset, which was based on national sources and the IMF survey Global Macroprudential Policy Instruments (GMPI). Such dataset was enriched using the cross-country databases used by Lim et al. (2011) and Altunbas et al., (2018), historical data from the MacroPrudential Policies Evaluation Database (MaPPED) and the integrated Macroprudential Policy (iMaPP) database.

Findings

According to our recent empirical findings, tightening macroprudential policies effectively reduces individual bank systemic risks. This suggests that implementing macroprudential policies first mitigates the negative effects of such risks, thereby increasing financial stability, and second, hinders instability pressures more effectively. That supports central banks’ desire to use more macroprudential policies in their policy formulations rather than relying solely on interest rate policies. Furthermore, imposing macroprudential policies on financial institutions, such as capital buffers, loan-to-value caps, levy/tax, foreign exchange, and countercyclical reserve requirements, as well as limits on household debt and loan-to-value ratio caps, appear to reduce bank systemic risk pressures significantly.

Importantly, tightening in both lender-targeted instruments and borrower-targeted Instruments appears to be most effective during good times. Regardless of the downturns or upturns, lender-targeted instruments are always effective in reducing individual bank systemic risks. Borrower-targeted instruments, on the other hand, while imposing limits on household indebtedness and loan-to-value ratio caps, do not appear to play a moderating role in bank systemic risks during upturns and downturns. This finding explains why policymakers prefer to use lender-targeted instruments first.

We also find that macroprudential policies may be ineffective during financial downturns, such as the current global economic conditions, and may thus have a counterproductive role by stifling economic activity, threatening financial stability. Finally, we discover that macroprudential policies have significantly different effects, depending on the characteristics of the bank: size (too-big-to-fail), leverage, liquidity, and concentration. Our findings suggest that macroprudential policies are more effective primarily through the channel of leverage.

In another work (Apergis, Aysan and Bakkar, 2021), we demonstrate that the use and effectiveness of macro-prudential policies may differ based on the different regulation enforcement and institutional settings. More specifically, institutional quality, high capital stringency, and moderate supervision support macroprudential policies in mitigating systemic risks, where’s these settings may affect differently the efficacy of borrower-targeted vis-à-vis borrower-targeted policies.

Conclusions and policy recommendations

Against this background, the main concern is not to restrict bank lending policies, particularly in OECD countries during the post financial crisis period. The primary motivation was to stimulate economic activity and thus to increase confidence in the overall economy. This will boost credit and reduce financial risks. As a result, we can interpret our findings as countries failing to ease their macroprudential policies, particularly lender-targeted instruments, in time to alleviate financial stability concerns following the global crisis. This sluggishness in easing macroprudential policies could be attributed to increased scrutiny of banks and the resulting regulatory pressure on the banking system.

We conclude that borrower-targeted instruments, in contrast to lender-targeted ones, are individually insignificant during upturns and downturns. This outcome is critical. Borrower-targeted instruments play an important role in mitigating systemic risks in the post financial crisis era. However, their impact may be felt over a longer time horizon, given that regulators are expected to be even slower in introducing borrower-targeted instruments (i.e., caps on debt-to-income ratio and caps on loan-to-value) and even slower in modifying them, depending on macroeconomic conditions. Hence, to achieve the shorter-term goal of improving financial stability, central banks could be more active in revising their stance on lender-targeted instruments. In this sense, our findings highlight potential policy errors during the post financial crisis period, at least among the OECD countries. Macroprudential policies, especially lender-targeted instruments, need to be reloaded under current global circumstances, while taking into account the institutional and regulatory environments in force.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Borrower- and lender-based macroprudential policies: What works best against bank systemic risk?, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money (2022)

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Andrea De Santis on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.