China’s technological strength has been increasing since the late 2000s, accounting for a significant share of patents. The technology landscape that was dominated by the US, Europe and Japan in the early 2000s is now much more polarised between US and Chinese offices. Antonin Bergeaud and Cyril Verluise show that while the gap in the quality of patents is also closing, there are some important points that question whether China’s contribution to the technology frontier will continue to grow.

China represents a growing and dominant share of all patents filed in the world. However, many question the relevance of the technological contents of these patents and ultimately the ability of China to contribute to pushing the world technological frontier. (e.g., see Koning et al., 2022) While many indicators point to the spectacular technological progress made by Chinese companies and scientists in fields such as artificial intelligence and semiconductors, China’s recent struggles to develop an mRNA vaccine illustrates how the institutional background can be a barrier to the development of new radical technologies.

In a recent CEP discussion paper, we propose to measure the innovative contribution of China using patent data. To do so, we develop a new machine-learning based methodology to retrieve patents associated with a given technology. This automated patent landscaping is then performed on a set of six new and representative high-growth technologies: additive manufacturing, blockchain, computer vision, genome editing, hydrogen storage, and self-driving vehicles. We then look at the relative contribution of the United States, China, Europe, and Japan in the development of radical innovations that have pushed the frontier on these different technologies.

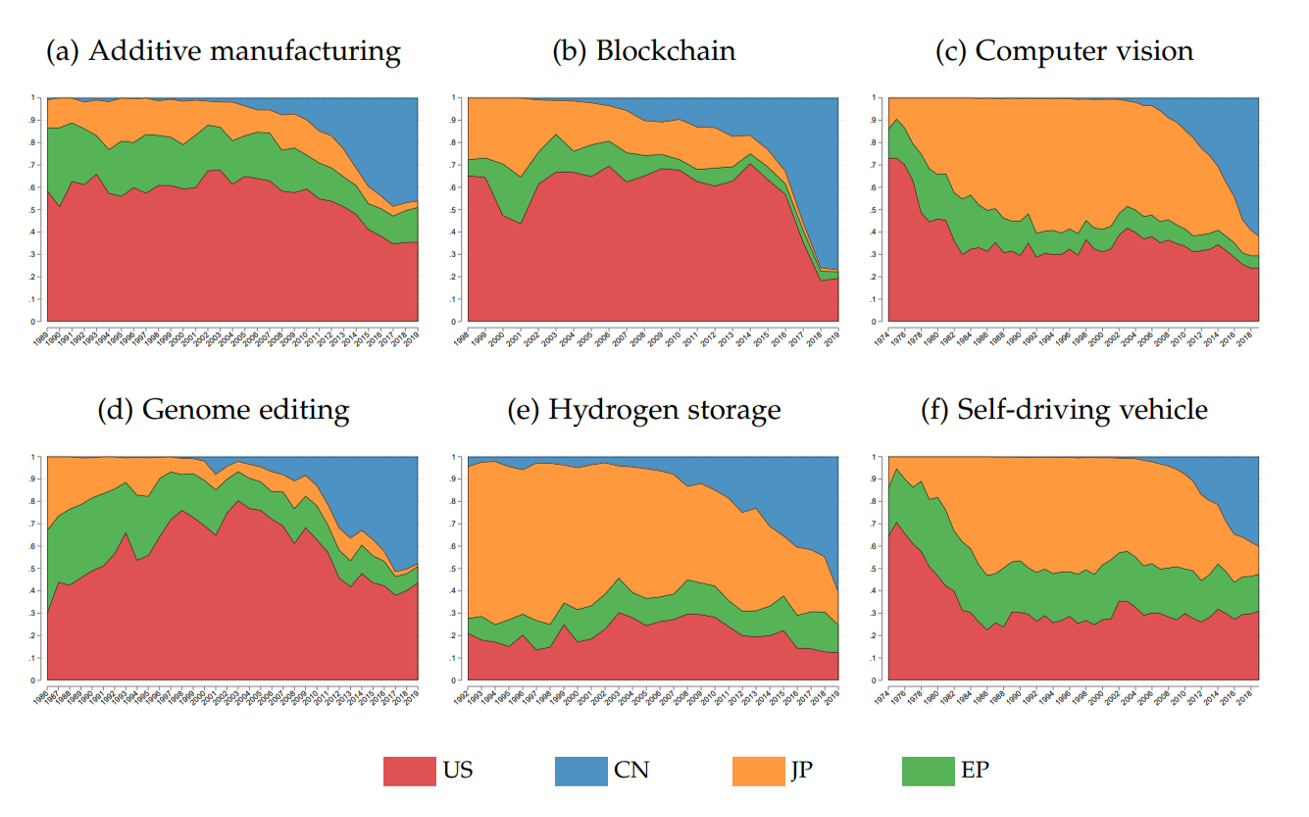

Our first finding is that simply counting the number of patents in each technology indeed shows the dramatic rise of China compared to the other countries as reported in Figure 1. This is especially spectacular in the case of the most recent technology, namely blockchain, for which China now holds 80 per cent of the patents and to a lesser extent for computer vision. This relative growth in China’s technological power is taking place against a backdrop of markedly heterogeneous trajectories within other regions. In particular, the share of Japanese patents collapsed to a very low level at the end of the period in favour of Chinese patents. This is consistent with recent studies documenting the declining centrality of Japanese firms and the loss of its position as a hub for both production and innovation in Asia (see e.g., Criscuolo and Timmis, 2018) Overall, the frontier technology landscape, once dominated by the US, Japan, and Europe, now appears much more polarised between the US and China.

Figure 1. Relative contribution to frontier technologies

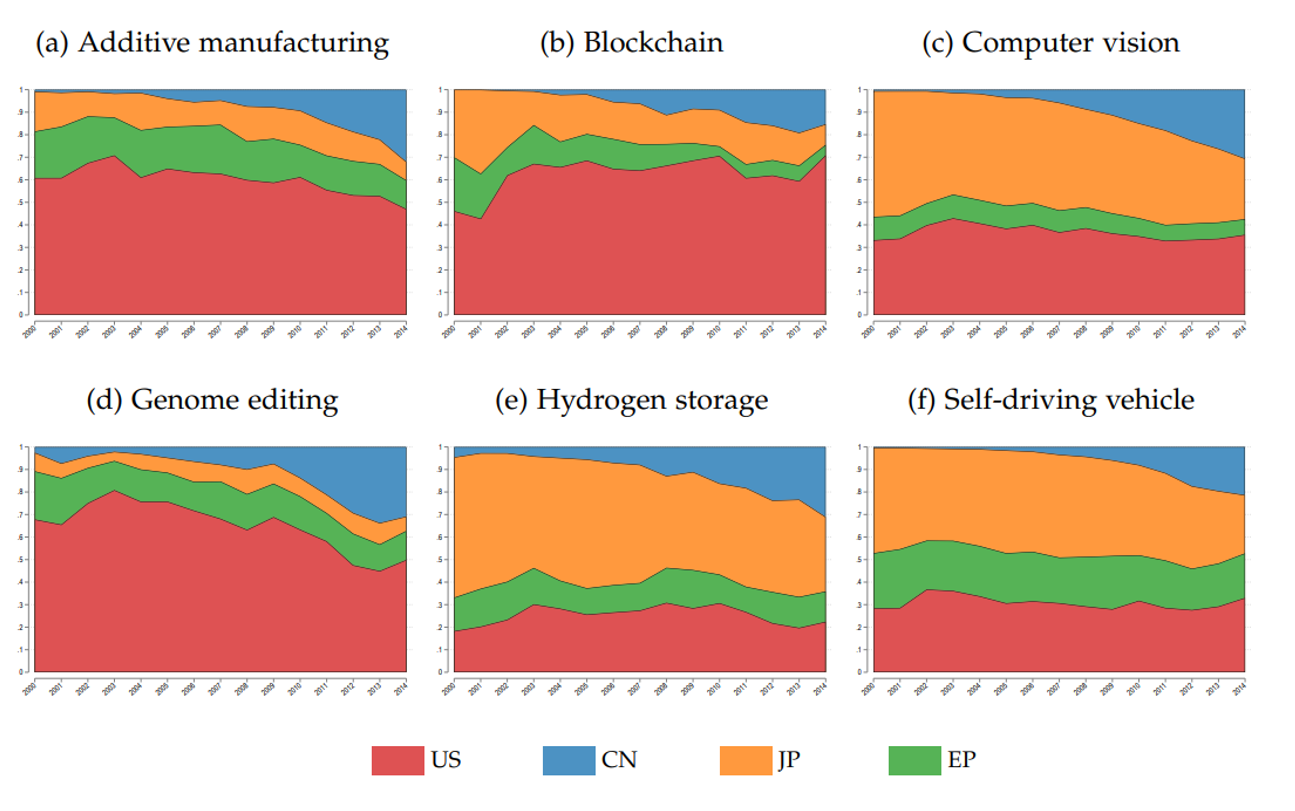

But this simple comparison of raw patent numbers does not really tell us much about China’s contribution to radical innovation, i.e., the milestones that accelerated the development of each of these six technologies. Scholars typically use a count of the number of patents weighted by the number of citations received to discriminate between truly influential patents and others. But, such an approach is particularly unsuitable for comparing countries with each other, as the propensity to cite is highly specific to each patent office. We therefore adapt a method popularised by Kelly et al., (2021) that uses the extent to which the semantic content of a patent differs from its predecessor and resembles its successor. A patent making a significant contribution to its field should in principle be at the same time novel and influential, a characteristic known as radicalness. We use this measure of radicalness to weight the count of patents for each patent office, in each year and for each of the six technologies. The results are reproduced in Figure 2 and show that while the advance of China is less pronounced than in Figure 1, China still catches up in terms of its contribution to each technology and has reached in most cases the level of Japan and Europe.

Figure 2. Relative contribution to frontier technologies – weighting by radicalness

So can China continue to make a significant contribution to the technology frontier and catch up with the US? One of the key outstanding questions is to examine the country’s ability to build domestic capabilities, that is: are institutions that foster the birth of new ideas being developed? Indeed, we have shown that China is increasingly contributing to advanced technologies that were developed before China’s technological takeoff in the late 2000s. The question of China’s ability to pioneer a new advanced technology therefore remains. This is especially relevant given that China’s most radical patents continue to rely heavily on basic scientific discoveries made in US and European laboratories. However, we show evidence that the development of these capabilities in China is on the rise. For example, the number of US patents that cite a Chinese patent as a source is much larger in 2019 than it was in the 2000s, and this is especially true regarding genome editing and blockchain.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on The rise of China’s technological power: the perspective from frontier technologies, Centre for Economic Performance, discussion paper CEPDP1876.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Odd Sun on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

very interesting analysis, the conclusion reminds me at the observation from Chris Freeman that the emergence of a new technological paradigm is accompanied by the rise of a new dominant player in the world economy. In the case of China this new technological paradigm is not yet visible; as you write, the inventions still rely heavily on basic discoveries made in US and European laboratories.