Governments’ efforts to reduce carbon emissions are falling short despite policies like ‘cap and trade.’ Anna Grosman, Aldo Musacchio and Gerhard Schnyder uncover the overlooked role of state-owned firms in exacerbating the issue, influenced by government involvement. They propose ways for these firms to become part of the solution to climate change.

Despite significant public attention and political efforts, there is a growing consensus among experts that current policy tools to reduce carbon emissions have fallen short of desired outcomes. Despite various initiatives such as subsidising renewables or introducing cap-and-trade schemes, global emissions continue to rise, failing to align with the urgent need for a net-zero transition. One often overlooked factor in this challenge is the role of state-owned firms, particularly in the energy sector, as some of the worst polluting organisations in the world.

State-owned firms have long been used as tools of governments’ industrial policy in many countries (Wright et al., 2021). While they have been successful in addressing market failures in some cases, their performance, both financially and in terms of environmental impact, is not always positive (Grosman et al., 2016). In the context of climate action, state ownership of polluting companies creates a dilemma for governments. On the one hand, state-owned firms provide governments with the power to accelerate the energy transition by internalising the costs, without having to rely on complex incentives or punitive measures for private firms to reduce emissions on a large scale. However, on the other hand, ownership of polluting state-owned firms often results in conflicting incentives within and across different branches of the government. Some ministries or politicians may rely on the income generated from polluting industries to finance public services or benefit citizens, while others, such as ministries of the environment, aim to reduce the activities of these firms.

This conflicting situation within governments highlights that the assumption that state-owned firms are purely “instruments of the state” is overly simplistic. The ability of states to effectively use state-owned firms to reduce emissions depends on various governance issues internal to the state bureaucracy itself (Butzbach et al., 2022). These issues may not be easy to solve, but it is crucial to involve state-owned firms in the global debate on climate action and set the right incentives to turn them into powerful tools for achieving net-zero targets.

State-owned firms and emissions: data evidence

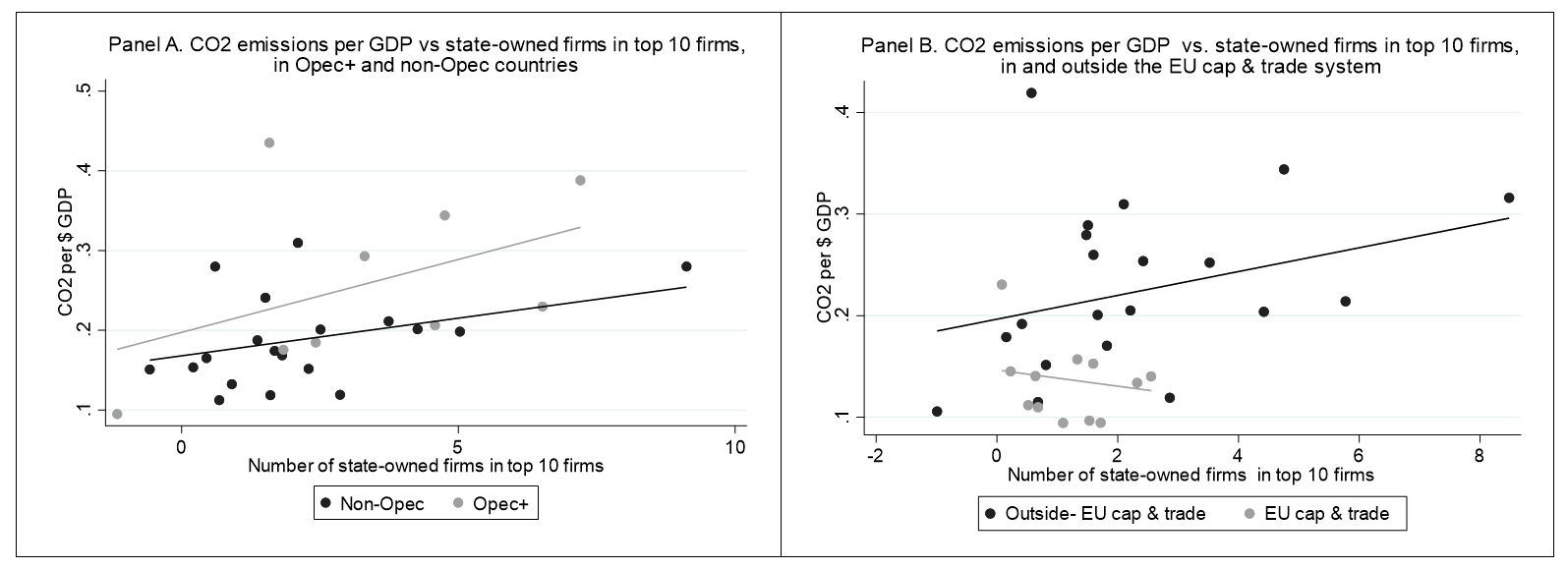

Data evidence shows that countries with high CO2 emissions per capita often have significant state ownership in major polluting industries. For example, countries such as China, India, Russia, Japan, Iran, and Saudi Arabia, where state ownership is extensive, are among the top ten most polluting countries in the world. This indicates a potential link between state ownership and fossil fuel dependence, which may counteract any positive impact of state ownership on emission reduction efforts. In fact, global data on state ownership also reveals a positive correlation between state ownership and carbon emissions, particularly in fossil-fuel-dependent countries like the members of OPEC+ (including Ecuador, Indonesia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Mexico, and Oman), where the commitment to cut CO2 emissions is often overridden by incentives to generate rents from polluting industries (Figure 1 Panel A).

Figure 1. Emissions vs. the number of state-owned firms in the top 10 firms (bin scatterplots)

Note: All figures are bin scatterplots, plotted using the binscatter command in Stata 17. Thus, we are grouping x-axis variable (number of state-owned firms in the largest 10 firms in a country) into equal-sized bins. The program then computes the mean of the x-axis and y-axis variables in each bin and creates both the bin scatterplot and an OLS-fitted line—this line is supposed to represent the best linear approximation to the conditional expectation function. Y-axis has the World Bank’s total CO2 emissions at the country level per dollar of GDP—i.e., GDP in PPP terms to make sure all figures are comparable across countries. The X-axis shows our estimates of the number of government-controlled firms out of the ten largest companies by revenues in 76 countries (control is defined as >50% of voting shares). OPEC plus includes OPEC member countries and Ecuador, Indonesia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Mexico, and Oman. The EU cap and trade system (EU Emissions Trading System) includes the EU 27 members as well as Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway and the United Kingdom. All data on emissions and EU cap and trade membership is for 2020. Data for state-owned firms is the latest available as of January 2023.

Conversely, state ownership of large firms is not always correlated with higher carbon emissions. In countries that have signed up for a cap-and-trade system — which caps firms’ emissions, provides emission allowances and allows for trading— such as many EU members, the correlation between state-owned firms and carbon emissions is actually negative. This suggests that regulatory tools, including cap and trade, can complement state ownership to produce positive outcomes in emission reduction. However, in countries without commitments to such schemes, state-owned firms tend to contribute to larger emissions rather than being used as a tool to combat climate change (Figure 1 Panel B).

The evidence also suggests that governments often face strong resistance to change from various powerful stakeholders associated with polluting state-owned firms. These stakeholders range from the workers and managers of these firms to the users of subsidised services, who object to higher tariffs to pay for the transition. For example, in Mexico, the state utility company CFE has tried to backtrack on agreements with independent producers of renewable energy, fearing that it would erode their monopoly. Emissions data we analysed is consistent with this evidence. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in electricity production by country are positively correlated with more state ownership of electricity firms.

Making governments and state-owned firms accountable

Taken together, our evidence indicates that for now, the government is oftentimes the problem rather than the solution to the climate crisis and state ownership of polluting firms is a curse, rather than a blessing. More widespread state ownership tends to go together with worse performance on climate change outcomes compared to countries with less state-dominated economies. This effect is further exacerbated for those countries that depend more heavily on polluting industries. Yet the example of EU countries that adhere to a cap-and-trade system shows that in this case the relationship is reversed. This suggests that complemented with the right policies, state-owned firms can become a powerful tool for climate action.

What is clear is that national and international policymakers need to be aware of these obstacles and consider them when devising laws or international agreements aimed at addressing the climate emergency. Global agreements need to include more decisive and prescriptive tools to track government and state-owned firm emissions as well as progress in national determined commitments. This will require detailed emission tracking, of not only CO2 but also GHGs, auditing by qualified organisations, education of officials and state-owned firms’ executives, and supervision from supranational institutions.

Similarly, civil society actors should increase pressure on their governments and state-owned firms to engage with climate change and expedite the energy transition. Pressure on private oil companies has been an important catalyst of climate action, but it is time to also force the ‘visible hand’ of the state toward making state-owned firms more sustainable.

The COP 28 conference will take place in the United Arab Emirates, and the Gulf region’s heavily state-dominated economies seem like the perfect setting to put the question of state-owned firms’ contribution to climate action front and centre of the global climate change debate.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post draws on insights from two academic journal articles: A) State-Owned Enterprises as Institutional Actors: A Hybrid Historical Institutionalist and Institutional Work Framework, by Olivier Butzbach, Douglas B. Fuller, Gerhard Schnyder and Liudmyla Svystunova, in Management and Organization Review, and B) State capitalism in international context: Varieties and variations, by Mike Wright, Geoffrey Wood, Aldo Musacchio, Ilya Okhmatovskiy, Anna Grosman and Jonathan P Doh, in Journal of World Business.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Chris LeBoutillier on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.