This was published by the China Global South Project on 4 March 2022. China Foresight is affiliated with the China Global South Project and regularly provides opinion pieces for the weekly IDEAS China Global South newsletter. Click here to subscribe to the newsletter.

Horrific images and stories of violence and destruction have reached us from Ukraine this week as Russia’s invasion is rapidly turning into a massive humanitarian crisis. While all eyes are rightfully on Ukrainians’ brave resistance, the human suffering that has ensued, and the deteriorating relationship between NATO and Russia, we’ve begun to wonder what the war in Ukraine and its geopolitical consequences may mean for China’s broader relationship with the Global South.

As we argued last week, leaders across the developing world are likely observing Beijing’s evolving position to the crisis, not least because of the dilemma it represents for China’s traditional foreign policy rhetoric emphasizing sovereignty and territorial integrity. Over the last week, China has indeed nuanced its initial position on Russia’s invasion. Initially, on the day before Russia’s invasion, China’s Foreign Ministry even blamed the U.S. for ‘creating panic and even hyping up the possibility of warfare’ and sided with Russian rhetoric the day after when referring to Putin’s ‘special military operation.’

Over the weekend, as the fighting became more violent and a swift Russian victory seemed increasingly unlikely, China’s official stance began to adapt, albeit only slightly. On Monday, in a phone call between China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi and his Ukrainian counterpart Dmytro Kuleba, Wang called on ‘Ukraine and Russia to find a solution through negotiations and the Chinese read-out stated that Kuleba ‘looked forward to China’s mediation efforts for the ceasefire.’ At the same time, however, China’s anti-Western rhetoric has remained prominent, China’s state media is still broadly supportive of Russia, and officials refuse to call out Russian aggression, instead referring ambiguously to the ‘Ukraine issue.’

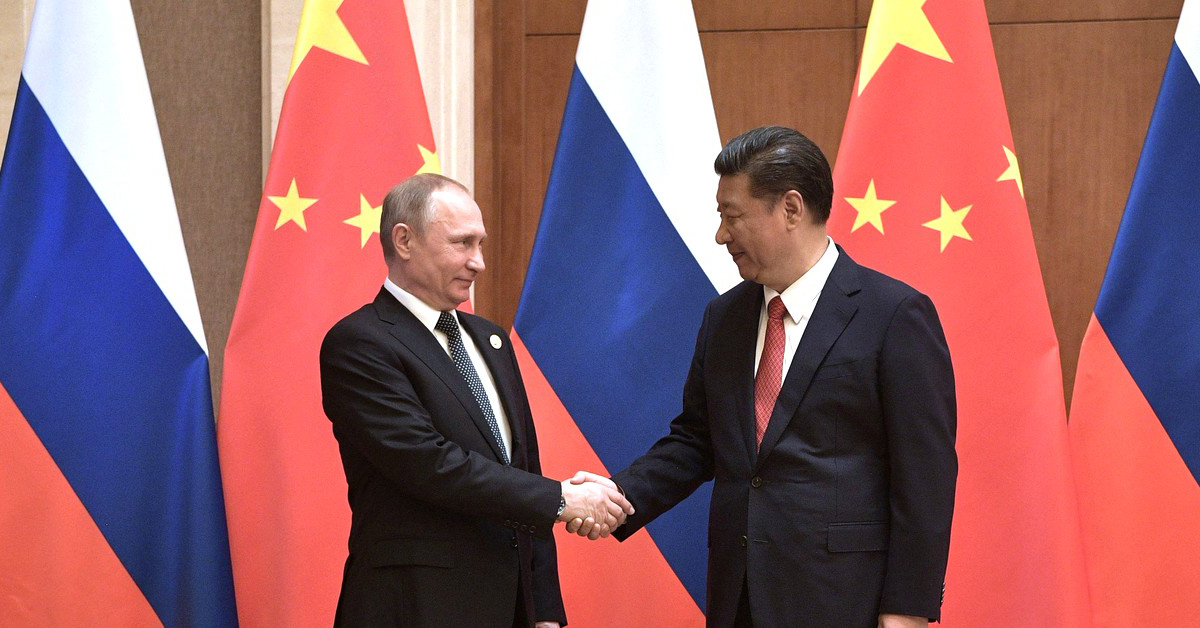

All this means that it is too early to judge whether Beijing actually intends to meaningfully leverage their close relationship with Moscow to contribute towards a diplomatic solution to the crisis or not. However, what is certain is that China’s next moves will be closely monitored by state leaders around the world – and especially across the Global South.

Societies and governments around the world have expressed solidarity with Ukraine and condemned Russia’s invasion over the last week. Some African countries, for instance, including Kenya, Ghana and Nigeria were quick to denounce the Russian invasion and express their support for Ukraine. On Wednesday, the UN General Assembly resolution condemned Russian aggression and called on Moscow to ‘immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw all of its military forces from the territory of Ukraine’ and was passed with a strong majority.

However, several countries have attempted to balance their interests vis-à-vis Russia (and likely, China) as well as Europe, the U.S., and their allies. 35 countries abstained from the UNGA resolution, including China and several African countries.

While abstentions may have country-specific reasons in each case, these responses to what many have identified as the largest military operation in Europe since the end of the Second World War, have nonetheless rapidly become a case study of 21st-century geopolitics – and China has a difficult role to play.

Beijing certainly wants to avoid being labelled as a supporter of ‘imperialist’ or ‘expansionist’ policies if it were to fully throw its weight behind the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This would not only harm its wider image as a ‘different’ external actor to the interventionist West but also make it difficult, if not near impossible, to maintain the rhetorical framing of China as the largest developing country and thus an all-weather friend of the developing world.

It will remain to be seen how long China will be able to hedge its bets in the context of a worsening Ukraine crisis and an increasingly violent Russian military campaign. While much is as of yet uncertain, powerful reactions from across the world over the last week show that outright support for a brutal war will come with reputational costs in the long run, across the Global South and elsewhere.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the China Foresight Forum, LSE IDEAS, nor The London School of Economics and Political Science.

The blog image, Vladimir Putin with Wang Yi (2018-04-05) 022, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.