- The crisis of the liberal order has been blamed on many specific factors, but in systemic terms flows from a fundamental clash of opposing ‘orders’ promoted on the one hand by the West led by the United States and on the other by Russia and China.

- The relationship between Russia and China has deepened significantly since the first Ukrainian crisis of 2014, and in spite of China’s stated concerns about the current war it has continued to back Russia diplomatically.

- As the war in Ukraine continues and becomes more destructive and dangerous, China will come under increased pressure to change course. But given the importance of the relationship to China, this is unlikely to lead to a rupture with Russia.

Liberal dreams

Two articles perhaps more than any other helped shape the debate about the nature of international politics after the Cold War: one written by Samuel Huntington of Harvard talked in almost apocalyptic terms of a coming ‘clash of civilizations’, the other penned by former State Department official Francis Fukuyama as the Cold War was winding down speculated in a far more optimistic fashion about a coming ‘end of history’. Written in the middle of 1989 the latter piece had very little to say about the end of the Cold War as such. Nor in spite of what some critics claimed, did Fukuyama imply that the world would now become some conflict-free zone. He merely suggested that there was no longer any serious alternative to liberalism. The long twentieth century marked by wars and revolutionary upheaval had at last come to an end. A less dangerous and more united world lay round the corner.

But how would once revisionist states fit into this new order? Fukuyama did not go into detail. However, the implication of his analysis was clear: those recalcitrants who had once stood outside the liberal order would now have no alternative but to join the only ‘club’ in town. Nor were leaders like Clinton unaware of the opportunity this presented. Indeed, as the end of the Cold War gave way to the so-called ‘unipolar moment’, the working assumption in Washington at least was that countries like China would over time become what US State Department official Robert Zoellick termed in 2005 a ‘responsible stakeholder’. This did not imply they would become democratic. On the other hand, it did suggest that as the material benefits of becoming participants in the world market became clear – China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001 – they would develop a vested interest in maintaining the peace and playing by the rules.

It was not just China, however, that could look forward to a new relationship with the West. So too could post-communist Russia. Putin might later have become the West’s enemy of choice. Yet it is still worth recalling that for a period at least – certainly up to the first Ukrainian crisis of 2014 – Russia appeared to be coming in from the cold. Thus it became the eighth member of the G7 in 1997 and remained inside the organization until 2014. Putin even made a state visit to Britain in 2003 where he dined with the Queen and made all sort of promises to the British business community that a new era in UK-Russia relations was about to open up. A few years later Russia also signed a series of agreements with the United States covering a whole range of issues from arms control to trade and investment. Then, in 2012, Russia joined the WTO itself. It is easy now to brush all this aside, even to claim (as some have done) that the West was being taken in. But for a while it very much looked as if we were set for a new era of global cooperation.

Realism redux

There is by now an increasingly large body of literature which purports to explain why this new ‘grand bargain’ failed to materialize. The list of causes is almost as long as the number of pundits now writing about what has widely come to be known as a ‘new’ cold war.

Some of course blame western liberalism itself and its various efforts either to alter Russia or China from within – regime change by any other name – or of naively seeking to make one or both countries partners in a new world order. Indeed, according to one author, America’s pursuit of a liberal agenda was not only naïve but also made the US excessively belligerent, which in turn pushed Russia and China into a corner from which they are now unlikely to return.

NATO enlargement has also been held responsible in many quarters for precipitating the current crisis. This argument has attracted a wide range of support, from large sections of the anti-American left, through to the IR theorist John Mearsheimer, and on to the one-time Ambassador to the former USSR, Jack Matlock, who sincerely believes that a promise was made to Gorbachev back in 1990 not to enlarge NATO and that this promise was subsequently broken.

Meanwhile, in the Indo-Pacific the responsibility for the deterioration in relations is either put at the door of China for acting in an ever more assertive fashion or – if you prefer to blame the US – of Washington for refusing to recognize China as a true equal and moving away from a policy of engagement to one of containment.

Nor, finally, should we ignore the role played in all this by the assumption of power in both China and Russia of two highly authoritarian leaders determined to make their mark on history by standing up to a West which, significantly, both assumed to be in terminal decline. Putin had certainly convinced himself that America’s era of dominance was fast coming to an end. The unipolar order, he noted in 2018, was ‘practically already over’; the American empire (like all empires before it) was now on the way down. China agreed. Taken together, the financial crisis of 2008 followed a few years later by Trump seemed to convince Chinese elites that the so-called ‘American Century’ was well and truly over, and that the United States was now in steep ‘economic and political decline’.

Clash of Orders

Convincing though all these partial explanations might be (at least for those advancing them) singly or even collectively they all ignore what really lies at the heart of the new disorder: namely a ‘clash’ between two visions of how the international system should be organized – one promoted in the West in which all states would and should continue to play by western rules within an international system still dominated by the United States and the dollar, and the other, articulated by China and Russia over many years in various fora from the BRICs to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which looked forward to a non-western, non-liberal order where the United States would no longer be the only serious player in the international system.

By the end of 2021 a senior Chinese official was insisting that the relationship between the two countries was now the best it had ever been in history.

At what point Russia and China began to articulate this vision is open to some interpretation. The outlines of it can certainly be found as far back as 2009 at the first BRIC summit held in Russia. It took further shape after Xi Jinping came to power and began to insist that instead of China fitting into the pre-existing international system ‘the international system would and should accommodate’ a ‘transformed China’. Following the first Ukraine crisis it took a sharper form still when China in effect threw in its lot with Russia. And it continued thereafter with a series of high level meetings (37 in total between Xi Jinping and Putin), various discussions and an almost endless number of communiques which quite a lot of experts in the West either didn’t bother to read, or if and when they did, regarded as being mere ‘hype’.

Yet hype is not a term that either Moscow or Beijing would have used to describe their relationship by the end of 2021. Indeed, in the year before the invasion of Ukraine, the relationship went from strength to strength with trade hitting a ‘record high’ and Russia continuing to be China’s largest supplier of weapons as well as its second largest source of oil imports. In October, China and Russia then held joint naval drills in the western Pacific for the first time; a month later they also conducted joint air patrols over the sea of Japan. Little wonder that by the end of the year a senior Chinese official was insisting that the relationship between the two countries was now the ‘best’ it had ever been in history.

Moreover, as their relationship became ever closer, that between Russia, China and the West moved even further apart. The signing of the AUKUS pact in September was provocative enough according Beijing. But when Biden hosted the first in-person meeting of the ‘Quad’ in September, followed a couple of months later with a summit of the democracies to which neither Beijing and Moscow had been invited, the divide between the two camps looked like it had become a chasm. The Russian and Chinese Ambassadors to the United States were even moved to compose an article together attacking the America-led Summit for Democracy, arguing it would only stoke up ‘ideological confrontation’.

Thus, as one year segued into another, relations between Russia, China and the West appeared to have reached rock bottom. This only seemed to be confirmed in early February when Xi Jinping and Putin met in Beijing at the start of the Winter Olympics. Here they signed a lengthy communique declaring – somewhat ominously, given what happened only three weeks later – that there were ‘no limits’ or ‘forbidden areas’ of cooperation. Russia and China then went on to stress their opposition to all those ‘actors’ – a less than subtle reference to the United States – who in their view continued ‘to advocate unilateral approaches to addressing international issues’ and persisted in interfering in ‘the internal affairs of other states’. Interestingly no mention was made of Ukraine. However, the document did make clear its opposition to any ‘further enlargement of NATO’. It also referred to Taiwan. Here Russia reaffirmed ‘its support for the One-China principle’ and confirmed ‘that Taiwan was an inalienable part of China’, and that Russia (like China of course) would oppose ‘any forms of independence of Taiwan’. The message could not have been clearer. If or when China took whatever measures it deemed necessary to solve its Taiwan problem, Russia would stand beside it.

Invasion

As social scientists we are often told that getting the future right is almost as difficult as understanding the past. Even so, if the past history of serious strategic thinking pointed to anything, it was certainly not to a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24th 2022. There were many good reasons to think this, but one clearly was the commonly held assumption that China, as the more cautious of the two powers, would do all in its power to dissuade Putin from launching his ‘war of choice’. Then, having done what many thought unlikely, a number of analysts and pundits begin to argue that Beijing was in such a quandary over the war that it would use any influence it had to curb Putin’s ambitions. When this did not happen, they then took it in turns to point out how embarrassed China was with what was going on; some even implied that this even might spell the end of what one China expert called this ‘shallow… marriage’ altogether.

This view of China as a neutral in the conflict is certainly one that China has been keen to promote. It also seems to have been taken up by many in the West. ‘China offers role as peace-maker’ proclaimed at least one headline on the 2nd March. Yet nearly one month into the war China has clearly not been persuaded to do what many in the West have been hoping – possibly anticipating – it might do and pull the proverbial plug on Putin. On the contrary, it has throughout the crisis – both before the invasion (which it denies is an ‘invasion’) and since – been fairly consistent in its support for the Russian leader. No doubt Xi Jinping has in his own words been ‘unsettled’ by the war and has called for ‘maximum restraint’ to be exercised. He might also be pained to see the ‘flames of war’ being reignited in Europe. He has even gone as far as insisting ‘Ukraine’s sovereignty and integrity must be protected’ (though without mentioning the fact that it is Russia’s actions which have led to the opposite). But it is difficult not to see all this as a diplomatic smokescreen obscuring the more significant fact that China continues to back Russia in a war which it may well have been informed was about to happen, and was only delayed – at least according to some sources – to permit the Winter Olympics in Beijing to come to an end.

If anything, far from criticizing Russia, China’s main target throughout has been NATO and the United States. Indeed, when asked to distant itself from Russian actions, the Chinese Foreign Minister responded in robust style by proclaiming that China’s friendship with Russia remained ‘rock solid’, and that however ‘sinister the international situation’ might be, the two nations would continue to ‘push forward’ their ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ into the ‘new era’. China certainly seems to have made good on this particular promise, to the extent of denouncing western sanctions as being ‘illegal’ while presenting the war on the ground from a Russian rather than a Ukrainian point of view. It even went as far as banning the showing of English Premier League football matches on Chinese TV just in case these revealed the widespread solidarity there was for Ukraine’s plight.

Nor has China been at all neutral in its coverage of the conflict at home. In fact, if we look at what is being said within China itself the line propagated seems unambiguously clear: that the real cause of the conflict is the United States and that if Russia can tie up the Americans and their allies in Ukraine then that is something China ought to welcome. This might not have prevented ‘all manner of opinions’ about the ‘conflict’ being voiced across Chinese social media, some of it highly critical of the government’s position. A group of five historians even attacked the government for backing Putin. But one instruction from the authorities directed at its media team summed up the official position with startling clarity: ‘do not post anything unfavourable to Russia or pro-Western’.

Futures

Coming to any hard and fast conclusions in the midst of a fast-moving situation would be most foolhardy. But through the ‘fog’ of this increasingly brutal war which has thus far killed and injured thousands and led to over two million Ukrainians having to flee, we should be able to draw a few tentative conclusions.

The first concerns the lessons we may or may not draw from the past. Analogies can sometimes be useful, sometimes not. However, as a number of analysts have pointed out, how China has acted in 2022 – sounding neutral while all the time backing Russia – is not that different to how it behaved eight years ago when Russia took over Crimea and intervened in eastern Ukraine.

The terms of China’s relationship with Russia have almost certainly changed for ever.

2014 however was a fairly speedy affair with relatively modest losses on the ground. 2022 is on an entirely different scale. Which brings us to our second point: as the war continues – as it seems set to in the middle of March – then China is going to find itself in the increasingly uncomfortable position of having to support an ally which in just under three weeks has become an international pariah. Moreover, if the war becomes more deadly and destructive, China is going to find out – if it is not doing so already – that its backing for Putin could very quickly lose it a great deal of the soft power it has been assiduously been building up over the past few years.

Perhaps more worrying still for a country highly dependent on the global economy, if the conflict starts to hit market confidence as a result of wild swings in the prices of raw materials and supply chain disruptions, then this could easily have downside consequences for the Chinese economy as well. As financial pundits always like to remind us, ’geo-political uncertainty leads to market volatility’, something about which China is bound to become increasingly nervous the longer the war goes on.

This brings us then to the balance within the relationship itself. As we have seen, even if China continues to back Russia, there is little doubt that the war in Ukraine is posing a diplomatic dilemma for Beijing, possibly even a ‘severe test’ according to Chatham House’s Yu Jie. Certainly, if the aim of the war was to weaken NATO or destroy Europe’s faith in US guarantees, then the policy has clearly backfired. Yet Beijing invariably plays the long game, and might indeed be calculating that whatever happens in Ukraine, Russia will in the end become ever more dependent on China. Whether this is something that either Russia will accept or China even wants is yet to be determined. Having a dependency may well be regarded in some circles as an asset. For others though it might well be seen as ‘more of a liability’.

In the meantime, the terms of China’s relationship with Russia have almost certainly changed for ever. As we have already indicated, this is unlikely to lead to a break with an ally with which it has been building a close relationship for years, whose view of the world is very similar to its own, whose hostility to the United States is just as great as its own, and whose support on nearly every international issue it values. That said, the calculation it now has to make about Russia is bound to have changed. A stable Russia led by a strong and predictable leader whose nation could boast extensive economic relations with Europe, was clearly a friend worth cultivating. Having a state led by a reckless leader whose economy is in free fall, whose relations with Europe have by now hit rock bottom, and whose list of enemies now seems to encompass nearly all of the most advanced economies in the world, is a very different proposition altogether. The Chinese leaders sitting in the isolated comfort of Zhongnanhai have much to ponder.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the China Foresight Forum, LSE IDEAS, nor The London School of Economics and Political Science.

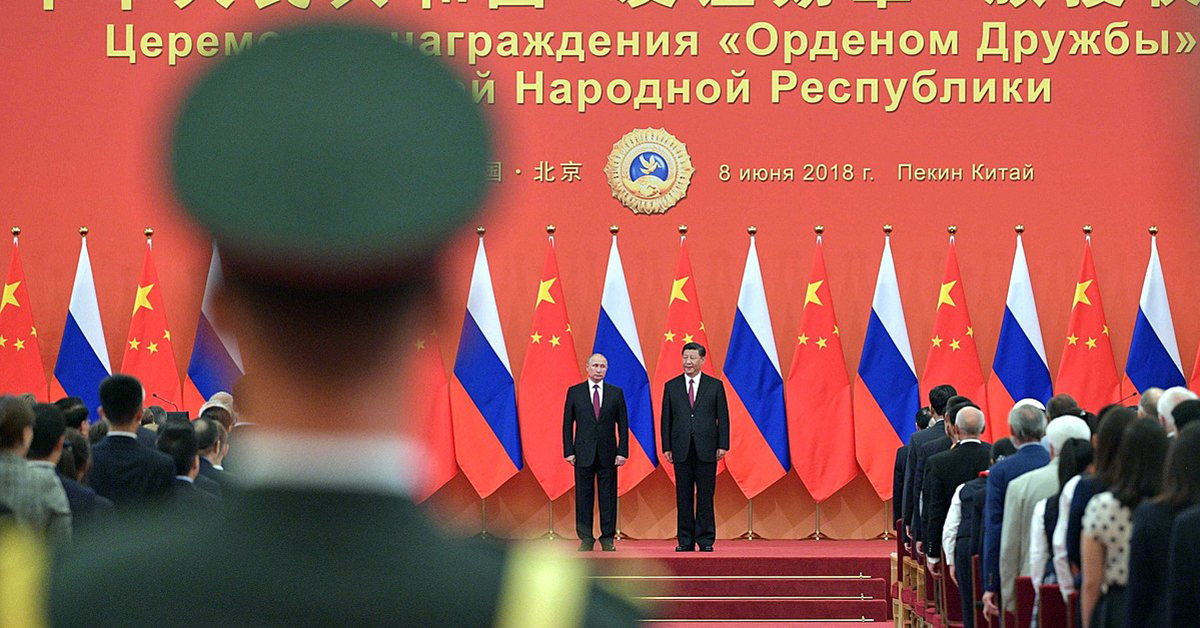

The blog image, “With President of China Xi Jinping2“, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

1 Comments