Shirley Ze Yu

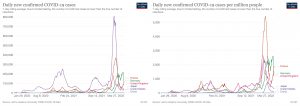

On March 27, China reported 1,219 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 4,996 asymptomatic cases. The 7-day rolling average began to decline. Measured alongside major economies, China delivers the lowest confirmed cases on an absolute basis and the lowest infection rate as a percentage of the population. Two new deaths related to COVID – more directly caused by age and health complications – were recorded for the first time since 2020, an astounding outcome given the Chinese population size. Empirical data can validate the effectiveness of China’s “zero-COVID” policy in containing Omicron so far. But the question remains at what cost? And for how much longer?

China imposed a draconian and archaic zero-COVID policy in Wuhan at the outburst of COVID in January 2020. Xi’an adopted a containment of equal severity in 2021 as the Delta variant raged.

The new zero-COVID policy emphasised a dynamic zero in 2022. “Dynamic” indicates fluidity across regions and communities, giving flexibility to local officials to adopt measures based on regional characteristics. The current wave of the dynamic zero-COVID policy highlights aggressive testing, preventive containment, and shorter quarantine periods to bring down the speed and scale of infections (R0) while causing minimum shocks to the economy.

However, a tale of two “zero-COVID” policies is at play in China.

The motivation to sustain a longer lockdown is stronger in the less developed regions in China. Contrarily, cities with more resources, healthcare support, and vibrant businesses tend to adopt policies with bigger elasticity on the zero-COVID policy to enable economic sustainability.

In the advanced economic regions, most prominently in mega-metropolises Shenzhen and Shanghai, the lockdown periods have become much shorter. Shenzhen was under a full lockdown for a week. The city was back to life on March 27. Over the week of lockdown, three rounds of testing were performed on over 20 million population. Isolating COVID spread from Hong Kong, one of the worst-performing cities in the world today, Shenzhen’s containment policy has been exceptionally effective.

Shanghai has announced a two-phase lockdown starting on March 28 for eight days. Divided by the Huangpu River, districts on the east and west sides of the river will enter sequential lockdowns for four days each. Shanghai may follow Shenzhen’s path to reboot the city’s economy soon after the eight days.

In the less developed regions, more conventional containment procedures are adopted, inheriting the spirit from Wuhan and Xi’an. Jilin province, an epicenter of this wave of COVID surge in China, has adopted the most stringent lockdown protocols. The lockdown will stay in place until 14 days after COVID cases reach a complete zero. Experts estimate the lockdown will persist in Jilin until early April. While Foxconn in Shenzhen and Tesla Super Factory in Shanghai were able to resume business after being locked down for 48 hours, the Volkswagen factory in Changchun, Jilin, remains closed after weeks.

Public health benefits and economic costs strike different equilibria between the economically affluent and less prosperous regions. The motivation to sustain a longer lockdown is stronger in the less developed regions in China.

Contrarily, cities with more resources, healthcare support, and vibrant businesses tend to adopt policies with bigger elasticity on the zero-COVID policy to enable economic sustainability.

Shanghai’s leading epidemiologist Zhang Wenhong wrote that massive testing in Shanghai has helped break the sharp exponential curve of the COVID surge. The daily COVID case report in China includes confirmed cases, asymptomatic cases, and imported and domestic cases. Asymptomatic cases have accounted for 70-80% of the total COVID cases uncovered so far, largely discovered through aggressive mass testing.

The COVID curve could have been a lot steeper had the asymptomatic cases not been discovered early and the source of infection not been reduced.

The dynamic zero-COVID policy allows businesses to swiftly open after days – not months – of lockdown. China’s COVID predicament is likely to induce more global supply chain shortages, particularly in high-end manufacturing, technology equipment, and chips, given the significance of Shenzhen and Shanghai in the supply chain.

The containment measure worsens China’s persistently weak consumption recovery. In order to achieve a 5.5% annual GDP growth in 2022, more fiscal stimulus will be needed to alleviate small-and-micro businesses from bankruptcies. COVID has inevitably caused shocks to China’s first-quarter trade and consumption. The most reliable support to the Chinese economy over this period will be the government’s drastic dose of infrastructure spending, including large digital and renewable infrastructure spending.

After global suffering from COVID-19 entered its third year, citizens are frustrated. The human cost of containment measures rises as patience diminishes. Chinese are no exception. Protests and frustrations are spotted at corners of grassroots communities, revealed on social media around the world.

It is less likely that we will see another major Chinese city locked down for 72 days in a Wuhan style in 2022. However, the cost to humanity and societies is beyond measurable. We remain uninformed as to what extent public coercion and data surveillance will change the fibre of modern societies when COVID becomes passé. In China, all is much less known.

Guy de Jonquières

After sailing through the early stages of COVID, China is hitting heavy weather. Its “dynamic zero-COVID” strategy of mass testing, lockdowns and travel bans, which previously suppressed the virus, is being severely tested by outbreaks that have spread to major cities including Shanghai and the manufacturing hub of Shenzhen. And China’s role as workshop to the world means shocks will not stop at its borders.

New infections are at their highest since their peak in 2020 and more than 50 million people are now in lockdown. According to Capital Economics, by mid-March infections were affecting areas producing half of China’s goods exports and shipping three quarters of them, threatening the global supply chains on which the world depends for many of its manufactured products.

These uncertainties have combined with the Ukraine crisis, mounting debt and a collapsing property market to cast growing doubts over whether China can hope to achieve its 5.5 per cent growth target this year.

China has so far limited disruptions by keeping factory lockdowns brief and re-routing exports through COVID-free ports, while businesses have responded by building up stocks and shifting production to elsewhere in the country and abroad. That has raised costs, adding to global inflationary pressures, but has kept exports flowing.

The fear, however, is that unless COVID can be quickly contained, Beijing will impose still stricter measures that could cripple large parts of manufacturing and the services economy. Indeed, the poor performance of China’s COVID vaccines and its rudimentary public health system could make that unavoidable.

So far, foreign companies appear determined to stay the course. The US Chamber of Commerce says only a fifth of its members have cited COVID as a reason for relocating operations. But that could change if worsening conditions reduce output of finished products and of vital components incorporated in those assembled elsewhere. Foreign investors, by contrast, are already running for cover and have recently been dumping Chinese shares, contributing to steep falls in the country’s stock markets.

Another sector that has already been badly affected by the Zero-COVID policy is international tourism. China’s travel bans have severely restricted foreign trips by its citizens, reducing their spending abroad by as much as $300bn. The hardest-hit region is south-east Asia, where the previous boom in Chinese tourism provided a bonanza for host countries. Although outbound tourism recovered late last year, it is still far below pre-COVID levels.

Likewise, Zero-COVID measures are making it harder for Chinese students to study abroad, putting at risk an important source of income on which many foreign universities, particularly in the US, Britain and Australia, have come to rely.

These uncertainties have combined with the Ukraine crisis, mounting debt and a collapsing property market to cast growing doubts over whether China can hope to achieve its 5.5 per cent growth target this year. If the engine of the world’s second largest economy stutters or stalls, that will be a worry, not just for President Xi Jinping and the Communist party, but for the rest of the world as well.

Ka Zeng

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese government has imposed strict restrictions to contain coronavirus outbreaks. Over the past two years, these policies have turned out to be successful in limiting infections and deaths within China which may otherwise have exacted a heavy toll on the country’s fragile health care system. They have also proven effective in ensuring the relatively steady supply of Chinese-made products to the rest of the world. However, as many countries which have chosen to live with COVID start to re-open, the economic costs of Beijing’s “dynamic-zero” COVID policy may gradually begin to outweigh its human benefits. This may accentuate the need for Beijing to reassess the policy to better adjust to changing internal and external circumstances and to minimise the disruptions of the pandemic to global supply chains and economic growth.

Going forward, the impact of China’s zero-tolerance COVID approach may depend on the degree to which the major players can recover from pandemic related restrictions. In the United States, for example, government fiscal support, along with strong labor markets and asset prices, have allowed for higher-than-expected economic growth in pandemic conditions. However, ongoing uncertainty about the country’s ability to effectively halt the spread of the virus stemming from the possible resurgence of COVID variants and vaccine hesitancy continues to cast a shadow on employment and economic activities. As supply chain bottlenecks and pent-up consumer demand led the Consumer Price Index to rise to 7.9 percent in the month ending in February 2022, the highest in 40 years, the Fed is poised to consider more aggressive interest rate hikes to combat inflation, potentially reducing employment and slowing economic expansion. Economic slowdown in the United States and elsewhere may in turn dampen the demand for Chinese goods and services and attenuate the impact of the supply chain disruptions caused by Beijing’s zero COVID strategy on the global economy.

Whether Beijing will be able to calibrate its COVID response and loosen controls may therefore have significant bearings on both Chinese and global growth trajectories in the years to come.

However, if the pandemic were to become endemic and if the development of new vaccines and drugs were to significantly reduce the health risks posed by COVID, then it is possible that the rest of the world may start to see increased mobility and the gradual return to normal economic activities. In this scenario, the COVID-related periodic shutdowns and factory closures in China may cut domestic consumption and demand, in addition to jeopardising the country’s ability to meet rising world demand and to capitalise on the benefits of global economic recovery. As many multinational corporations operating in China are already contemplating contingency plans to include the relocation of production to either third countries or the home country, they may also raise questions about whether China can maintain its successful record in attracting and retaining foreign investment. Along with significant fiscal expenditures for fighting COVID-19, the policy may curtail government investments in productive sectors of the economy and limit the degree to which Beijing can achieve its goal of promoting sustainable economic growth by incentivising the development of high-tech and services industries.

Such downward pressure on the Chinese economy may generate ripple effects throughout global markets, with potentially negative implications for global economic growth. Whether Beijing will be able to calibrate its COVID response and loosen controls may therefore have significant bearings on both Chinese and global growth trajectories in the years to come.

Alicia García Herrero

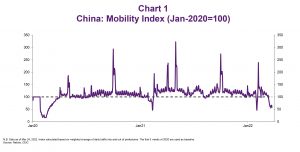

Since the COVID pandemic started in late January 2020, China’s borders have been closed to the world and domestic mobility has been reduced with different intensity in a larger number of locations. The most acute reduction in domestic mobility took place in Wuhan and surrounding areas but resumed rather swiftly in the second quarter of 2020 (Chart 1). In fact, China was the first major economy in the world to experience a rapid economy recovery. Still, the growth of disposable income, as well as consumption, has remained stubbornly weak until today. Renewed containment measures were taken in a couple of occasions, namely close to last year’s Chinese New Year as well as during the last few weeks in a more intense manner. The sharp reduction in domestic mobility since mid-February is clearly having a toll on China’s consumption but has not yet tainted China’s manufacturing capacity.

All in all, the global impact of China’s domestic containment measures is mixed. On the one hand, China’s ability to continue to produce goods to the rest of the world while major manufacturing centres, like Germany, South Korea or Japan, were in lockdown, obviously helped control inflationary pressures globally as well as the scarcity of goods. On the other hand, China’s lacklustre domestic demand implies that, this time around, the global economy has not relied on China as much as it did in 2008; if anything, China has relied on the rest of the world. In fact, external demand was a very important contributor to China’s strong growth in 2021 (1.7% contribution to the 8.1% GDP growth).

[A] consequence of China’s closed border is the increasingly negative sentiment of Chinese people as concerns the rest of the world as well as the increasing disconnect of the rest of the world with what is happening in China

In addition to domestic containment measures, it is important to recall that China’s closed borders for nearly two and a half years also have an important – and unfortunately very negative – bearing on the global economy. First of all, the plummeting numbers of physical exchanges between China and the rest of world, including business exchanges, is one of the main reasons why China’s outward foreign direct investment has stalled since the pandemic started. This is particularly relevant for emerging economies with large financing needs since they rely on external capital to build their infrastructure and upgrade their industrial capacity.

The second unintended consequence of China’s closed border is the increasingly negative sentiment of Chinese people as concerns the rest of the world as well as the increasing disconnect of the rest of the world with what is happening in China. The much larger number of COVID cases in most countries of the world, when compared with China, developed a strong impression among Chinese citizens, of security at home and risk elsewhere, resulting in a waning interest about the rest of the world. This obviously does not bode well for future scientific or business collaboration between China and the rest of the world although it is very hard to measure its immediate impact on the global economy. A good example of how much strict borders contribute to dystopian views of the other is the state of affairs of the global economy at this current juncture with a war in Ukraine and its devastating consequences, not only for Ukraine and Russia, but actually for the world.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the China Foresight Forum, LSE IDEAS, nor The London School of Economics and Political Science.

The blog image, “Shanghai“, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.