Sign up for China Foresight’s upcoming events here.

- Strategists in Beijing tend to think of geopolitics in terms of geometries, especially strategic triangles and the concentric circles of tianxia (“all under heaven”).

- China’s strategic triangles should be understood as United Front Work, which are intended to join with one group of ‘friends’ to isolate and attack another group of ‘enemies’.

- Both China and Russia present their own models of global concentric circles. Here China and Russia are each at the centre of their own world orders, and each is at the periphery of the other’s, which eventually will lead to conflict.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has complicated relations not just with the US, but also with China. But how are we to understand China-Russia relations, and what can this tell us about their models of world order?

Strategic triangles as tactical United Front Work

Strategists in Beijing tend to think of geopolitics in terms of geometries. Strategic triangles have been used to make sense of shifting alliances between China, Russia, and the US over the past century. In 2022, we see China and Russia banding together in a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership that, as Putin and Xi Jinping declared just before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, has ‘no limits’. But this is neither new, nor unique. China has a long history of strategic triangles, joining with the US in World War II to fight Japan, signing a treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union in 1950 to counter the US, and shifting to the US in the 1970s to balance against the Soviet Union.

China’s triangular diplomacy is pervasive, but is it a long-term strategy or a short-term tactic? If it is a strategy, then we should see China forging alliances with countries that share its values, interests, and goals. There’s evidence for this strategy in multilateral organisations where China is a leader: BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank. But are they really alternatives to the existing world order of the G7, NATO, and the IMF/World Bank?

China-Russia-US triangles actually make more sense when viewed as a tactic that is less the positive sharing of ideas and ideology among allies, and more the negative hedging of interests. Beijing is allergic to alliances: it only has one treaty ally, North Korea, and according to diplomatic sources in Beijing the alliance has been meaningless since the 1980s. China’s aversion to alliances comes from its experience as the target of alliances: according to Beijing, the US alliance system in Asia is an evil plan to encircle and contain the PRC.

Rather than think in terms of alliances, it is best to understand strategic triangles as United Front Work, a communist party tactic that was created by Lenin in 1920, and then developed in Soviet and Chinese practice. The logic of United Front Work is to join with one group of ‘friends’ to isolate and attack another group of ‘enemies’. In the 1930s, the Nationalist Party (KMT) and the CCP fought each other in a civil war. But once World War II erupted, the KMT and the CCP decided to stop fighting each other in order to fight Tokyo together. Once Japan was beaten, the primary contradiction was between the CCP and the KMT again, so the CCP united with non-communist groups to fight against the KMT. After the CCP came to power in 1949, United Front Work has continued in both domestic and international politics, as seen with China’s shifting strategic triangles: when the US is the primary enemy, Beijing unites with Russia; but when Russia was the primary enemy, Beijing unites with the US.

This is what China and Russia mean when they talk about a ‘multipolar world’: it’s not just against American unipolarity, but also entails a shifting pattern of temporary agreements that don’t add up to a stable world order. While Xi often waxes lyrical about China’s value-based Community of Shared Future for Mankind, we should remember that Beijing’s favourite American diplomat is Henry Kissinger, and their favourite American president with Richard Nixon. The adage ‘Only Nixon could go to China’ underlines how strategic triangles aren’t about ideology, but involve precise calculations of temporary advantages in a shifting geopolitical ecology.

This is the best way to make sense of the current Putin-Xi Jinping ‘no limits’ bromance: it will work until one of the countries decides that the other is getting too powerful. It’s also important to note that each shift in triangular diplomacy was accompanied by war: World War II, the Korean War, the Sino-Soviet border war in 1969, the Chinese invasion of Vietnam in 1979, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Strategic triangles thus are an unstable system that leads to war.

Tianxia’s concentric circles

The other way of thinking about China-Russia relations is in terms of circles, especially the concentric circles of China’s alternative world order: tianxia, meaning “all under heaven”. Russia and China are united in the current strategic triangle not just by concerns over US unipolarity, but also by a distaste for liberalism, which both countries see as an ideological threat working to overthrow them through a ‘colour revolution’ like the one we saw in Ukraine in 2014. Moscow generally fights against liberalism by using sharp power to sow division and conflict in democratic societies. This is a negative tactic that doesn’t provide an attractive alternative ideology or value system.

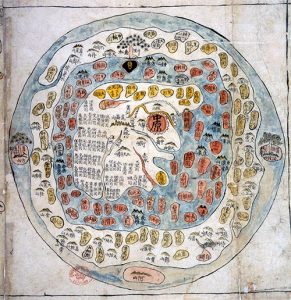

Figure 1: Tianxia Map, 18th century

China, on the other hand, presents a positive ideological alternative: tianxia. The best way to explain tianxia is to look at the ‘Tianxia Map’ from the 18th century. It’s a territorial map that puts China at the centre of the world. It’s also a civilisational map that shows China as the centre of civilisation, which fades out to barbarism at the periphery. Lastly, it’s a religious map because China here is at the centre of the universe, the cosmological node that joins heaven, earth, and humanity. In this way, tianxia is a long-term cosmological strategy, rather than a short-term geopolitical tactic.

The ‘Tianxia Map’ is from early modern China, and is now popular again because it reflects how the ancient Chinese idea of tianxia has been rebooted to solve the world’s problems in the 21st century. We’re told that the tianxia system is better than the current liberal world order because it offers ‘peace, general security, and civilizational vigor’. Rather than look to individuals or nation-states as the focus of politics, tianxia makes us think about the problems of the world from the perspective of the whole world. Yet as the Tianxia Map reminds us, this is a hierarchical system that puts Beijing at the centre of the world, and exports Chinese ideas of order and governance to the rest of the world. If this sounds like imperialism, that’s because the Chinese empire is increasingly presented by Beijing as a model for future world order. Tianxia’s concentric circles also echo the CCP’s understanding of its role at the centre of everything: ‘Party, government, military, civilian, and academic; east, west, south, north, and centre, the Party leads everything’.

Rather than joining with temporary friends in a strategic triangle for tactical advantage, the tianxia system aims to start in the centre at Beijing and spread civilisation and empire out to the world. Rather than multilateral or multipolar, tianxia is fantastically unipolar: there is only one centre, one civilisation, and as the slogan for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics declared: ‘One World, One Dream’.

Interestingly, post-Soviet ideology in Russia runs along similar lines. Putin’s Eurasian ideology presents a Russo-centric view of the world. It is founded on the religious centrality of the Russian Orthodox Church, and its cosmological power radiates out into the territories of the former Soviet Union – and beyond. Kyiv is central in this narrative as the birthplace of Russian Orthodox civilisation, so as Putin explained in 2021, Russia can’t be Russian without Kyiv.

Both models of global concentric circles assume the rejuvenation of Chinese and Russian civilisation, whose rise is predicated on the simultaneous fall of the West into immoral corruption. If this logic of inter-civilisational conflict sounds remarkably like Samuel Huntington’s ‘Clash of Civilizations’, that’s because this understanding of world order is very popular among conservatives around the world. It’s popular in Beijing, Moscow, Delhi and Riyadh because it gives recognition and respect to what such conservatives see as their core civilisations.

So how do Putin and Xi see global order? Triangles and circles present very different views of the world and of politics. On the one hand, strategic triangles are multipolar, and require careful attention to shifting geopolitical circumstances. Triangles are more negative than positive, and present Xi and Putin as a paranoid pair hedging against the hegemon, rather than as leaders of two great powers confidently uniting according to shared ideas.

On the other hand, concentric circles evoke a unipolar order that creates grand projects to spread ideology, civilisation – and empire – around the world. Here China and Russia are each at the centre of their own world orders, and each is at the periphery of the other’s, which eventually will lead to conflict.

In Beijing, both triangles and circles remain popular among strategists. But talk of strategic triangles seems dated, reminiscent of the ‘Cold War mentality’, while tianxia’s circles are increasingly popular as a way to express China’s newly revived tradition that speaks to the centrality of the CCP, and to the centrality of Xi Jinping as world emperor.

ONLINE EVENT: On Tuesday 1st November at 03:00pm, LSE IDEAS’ Russia-Ukraine Dialogues and China Foresight will welcome Yu Jie, Björn Alexander Düben and Lukas Fiala to discuss the evolving relationship between China and Russia. Sign up here.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the China Foresight Forum, LSE IDEAS, nor The London School of Economics and Political Science.

The blog image was generated by DALL-E 2.