The pandemic means that governments want data faster than ever before. Timely data is vital if we are to avoid the lack of preparedness that characterised the initial response to COVID-19, write Jose A Bolanos and Andrei Guter-Sandu (LSE). But speeding up and increasing the quantity of data available carries real risks and challenges.

Having the ‘right’ data at the ‘right’ time

The demand for reliable data with which to make policy decisions is hardly new. The growth of the welfare state after the second world war required large amounts of data in order to develop and pursue policies. The ubiquitous ‘GDP’ measure, for instance, took off in this period. This process was amplified by the proliferation of regulatory agencies and the extension of regulatory oversight over the past three decades. Data science units have become commonplace in governmental departments all over the world.

So the extraction and production of data is a mundane dimension of public policy. However, the issue of its timeliness is sometimes overlooked. Data does not fall from the sky: it needs to be collated, unified, reported, and ultimately analysed. This ‘quantification’ process is one of the things that can lead to delays in reporting. These delays are problematic because at some point, data about the activities of people becomes a historical record rather than an actionable asset. Alas, while there had always been some interest in having timelier data for public policy, such interest had not been pursued with such urgency until COVID-19.

The pandemic has significantly accelerated demand for timely data vis-à-vis surveillance. Even China, where surveillance was already extensive, saw a need to rapidly install additional cameras outside (maybe even inside) apartments to ensure that citizens did not flout the lockdown. Tracing apps, which are likely to become prominent features in the fight against and recovery from COVID-19, share a basic premise: track a person and provide a real- or near-real-time assessment of the risk of infection associated with that person. Furthermore, as countries move into recovery, the acceleration effect may expand beyond surveillance.

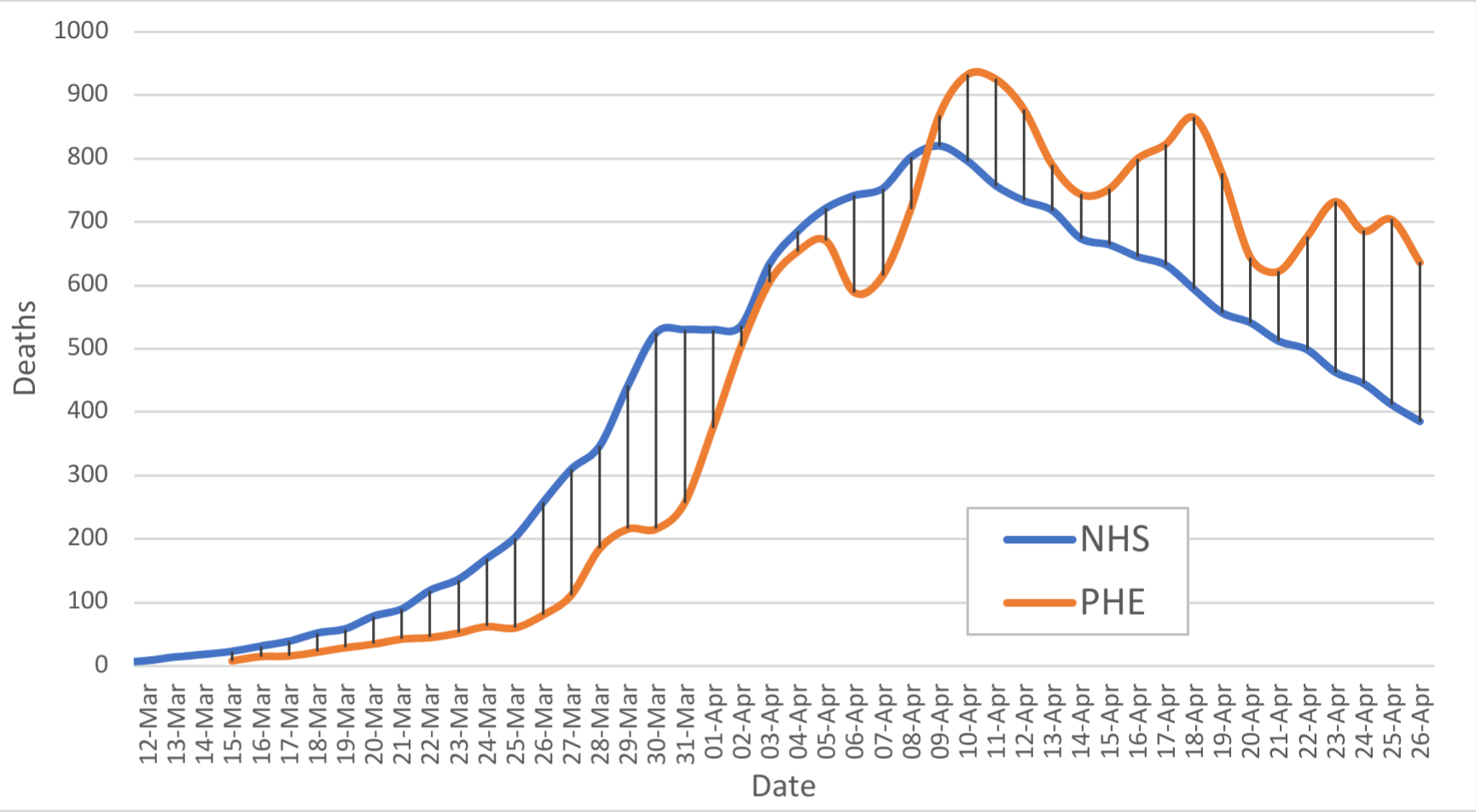

The statistics about cases and deaths from COVID-19 are likely to be subject to calls for timelier data. Up until recently, for example, the principal source of statistics about the number of deaths in the UK was a dataset by Public Health England (PHE) that reports deaths as per day of registration rather than the day in which the person actually dies. As shown in Figure 1, PHE’s dataset incurs a delay to NHS statistics, which report fatalities as per the day of death.

Figure 1: Daily hospital deaths from COVID-19 in the UK (rolling 3-day average). Sources: NHS, PHE.

It currently takes about a week for the NHS to have a final number of the number of deaths on a given day. Consequently, the NHS numbers are a retrospective look rather than a live image. That said, while the differences should balance out over time, Figure 1 shows how the NHS statistics rise and plateau faster than PHE’s. If the NHS could track deaths in real time, UK policymakers would be able to tighten or ease social distancing restrictions in a timelier manner. The same rationale applies to care home deaths or even excess deaths: the faster the reporting, the more dynamic the recovery. Unsurprisingly, high-level government officials in the UK are already calling for legislation to force citizens to register non-hospital deaths much faster than currently.

Future challenges

While there is room for concern about the extent to which policymaking is over-reliant on data, political leaders nowadays want to base their decisions on sound data. So COVID-19’s acceleration effect will likely persist throughout the current crisis and its recovery. Having timelier data may lead to better-informed policy decisions, but the accelerated nature of the transition may exacerbate other social, political, and economic issues that also matter in the context of recovery. Four of these are particularly salient:

• Privacy. To have statistics in time to make data-informed decisions in complex situations like COVID-19, governments need to either have real time or near-real time data across areas of human activity by the time a need arises, or be able to rapidly raise quantification efforts in selected areas. Both alternatives imply privacy sacrifices that may not be discussed thoroughly in an accelerated transition.

• Quality of data. Urgency may erode the quality of the data used for decision making. Consider, for instance, R0, which is considered critical to the decision of when to ‘flip the switch’ between lockdowns and other stages of the recovery. R0 is notoriously difficult to pin down given debate about how to count deaths, calculate the mortality rate, and estimate real infection rates. Acceleration increases the risk of scientific guesstimates like R0 becoming even less accurate (‘rougher’) than currently.

• Temporality of policymaking. A move from long-term planning to the immediacy of real-time data and crisis-firefighting shrinks the policymaking horizon, which might have significant consequences. Lockdowns, for example, are known to exacerbate short-term socio-economic inequalities. As a result, acceleration may lead to having much data to address short-term issues at the expense of interest, attention, or political bandwidth to address long-term challenges.

• Capacity in the Global South. COVID-19 is global. Restarting globalisation will likely require real- or near-real time data capacities across the world, which is particularly difficult in the Global South due to lack of infrastructure and capacity. Difficult choices lie ahead in terms of reallocating scarce resources to developing data capacities in the Global South.

The myriad sacrifices needed for data to be available – and the debates about the limitations of data – do not go away with the pursuit of more timely data. Rather, they risk being ignored. Consequently, the accelerated effect we describe here, while perhaps necessary, risks exacerbating several other social, political, and economic issues that also matter to a successful recovery. This means we need to expand the analysis of what the ‘right’ data is, and consider its timeliness too.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

Very concise synthesis of the main challanges. Thanks for sharing it.

I would stress the importance of current ‘other threats’ to Democracy around the World, like Populism, which make even more important the need to protect privacy (i.e. protect it from the next populist strong man), as well as protecting Democratic Institutions from short term decision making.

Heiner (Costa Rica)