States have tried to limit people’s movements in an effort to contain COVID-19. But keeping people out of cities denies them the ability to better their lives and escape from persecution and repressive hierarchies. Underground economies will flourish unless we empower city authorities to act independently, says Loren B Landau (University of Oxford and University of the Witwatersrand).

This is a response to Romola Sanyal’s LSE Festival talk, After COVID, What Next for Urban Humanitarian Responses? Join in the discussion by posting a comment below.

The pandemic has exacerbated inequalities – even as it empowers police and planners. It has stimulated mass evacuations and remarkable efforts to contain mobility. As Romola Sanyal accurately observes, it exposes the frailty of public welfare systems and the state’s coercive inclinations, and reflects an acute assault on the wellbeing and future of millions of urban residents.

Even before the pandemic, many governments were wary of refugees and international migrants living in their cities. Many also tried to slow the movements of their own citizens into under-resourced urban centres. COVID-19 has heightened these restrictions, and the effects have been both immediate and long-term. Those forced to be on the street in order to live or work are now being labelled vectors. This stigmatisation helps cement social boundaries, and prompts additional restrictions.

Sanyal eloquently captures many of these short-term effects on livelihoods and welfare. But the reactions to COVID – the long-term social and policy consequences – go far beyond that. They are not only not only about reshaping movement, but also about reshaping futures. In a world where economies are spatially concentrated, in regions where families expect and incorporate the absences of migrant workers, and for individuals whose sense of progress demands mobility, undermining mobility becomes geographic and temporal entrapment. For decades, migration represented the possibility of a step in to the modern. Postmodern imaginations are infused with an acute awareness and orientation to ‘multiple elsewheres’ – giving the freedom to cross boundaries even more significance. Movement for many is not just a means of survival or economic accumulation. It is a rite of passage: a means of claiming a future.

Excluding refugees, internally displaced people and other migrants from public spaces means robbing people of potential. The urban and rural poor – including those displaced by war and environmental disaster — depend on relatively spontaneous forms of movements and translocality to negotiate the uncertainties of the informal economy. Without secure jobs, housing, or services in a single location, people often shift locales and social networks in an effort to avoid becoming marooned in time and space. For the young, an ability to move can represent a chance to escape patriarchal, heteronormative, or generational hierarchies and open opportunities for personal growth and profit. Hundreds of thousands are contained in camps from which they are now even less likely to be released into space where they can build their own lives. Mobility and translocalism has become a way to negotiate these uncertainties: to build connections across space that offers some chance at resilience and possibility amid precarity.

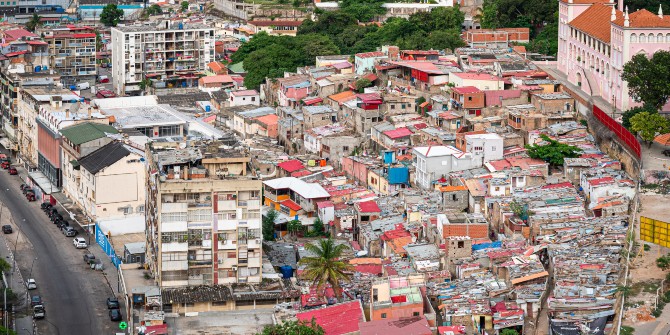

For African countries faced with a burgeoning and remarkably youthful population – whose prospects for local employment were already deeply constrained – keeping people out of cities means trapping them in perpetual rural poverty or precarious urban lives. Underground economies will flourish and the possibilities for effective, humane planning and public investment will be eroded by shrinking revenue streams, corruption, and criminality. This will ultimately hurt everyone – wealthy and poor, mobile and sedentary.

Sanyal ends her presentation by appealing for a greater response at the local level: counting, solidarity, and participation. These are important, but by themselves they ignore the short-term political incentives of marginalisation and exclusion. Instead, we need interventions that can incentivise and empower municipal authorities to respond in ways that are inclusive, equitable, and long term. Direct aid to particular groups may save lives in the short term, but may also heighten tensions in ways that promote scapegoating and victimisation. Instead, the global aid agencies should decentralise campaigns to assist urban refugees, and incorporate the displaced into a broader set of initiatives to improve planning, investment, and spatial equity.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.