We may need to vaccinate under-18s to get the pandemic under control. Patrick Sturgis (LSE), Lindsey Macmillan, Jake Anders and Gill Wyness (UCL Institute of Education) on the findings of a UCL CEPEO / LSE COVID-19 survey that shows a third of young people have doubts about taking the vaccine, with hesitancy significantly higher among non-White respondents.

Children and young people are, mercifully, at extremely low risk of death or serious illness from the coronavirus. For this reason, they are likely to be the last demographic in the queue to be vaccinated, if they are vaccinated at all. Yet there are good reasons to think that a programme of child vaccination against COVID-19 will eventually be necessary in order to free ourselves from the grip of the pandemic. In anticipation of this future need, clinical trials assessing the safety and efficacy of existing COVID vaccines on young people have recently begun in the UK.

While children and young people experience much milder COVID symptoms than older adults, there is currently a lack of understanding of the long-term consequences of infection across all age groups, and there have been indications that some children may be susceptible to potentially severe and dangerous complications. Scientists also believe that immunisation against COVID in childhood may confer lifetime protection, reducing the need for large-scale population immunisation in the future.

Most importantly, perhaps, vaccination of children may be required to minimise the risk of future outbreaks. If substantial numbers of adults refuse immunisation and the vaccines are, as seems likely, less than 100% effective against infection, vaccination of children will be necessary if we are to achieve ‘herd immunity’.

We now know a great deal about COVID vaccine hesitancy in general populations from a large and growing body of survey and polling data and, increasingly, from actual vaccine uptake. Much less is known, however, about vaccine hesitancy amongst children and younger adults. Here, we report preliminary findings from a new UKRI funded survey of young people carried out by Kantar Public for the UCL Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunity (CEPEO) and the London School of Economics. The survey provides high quality, representative data on over 4,000 young people in England aged between 13 and 20, with interviews carried out online between November 2020 and January 2021. Methodological details of the survey are provided at the end of this post.

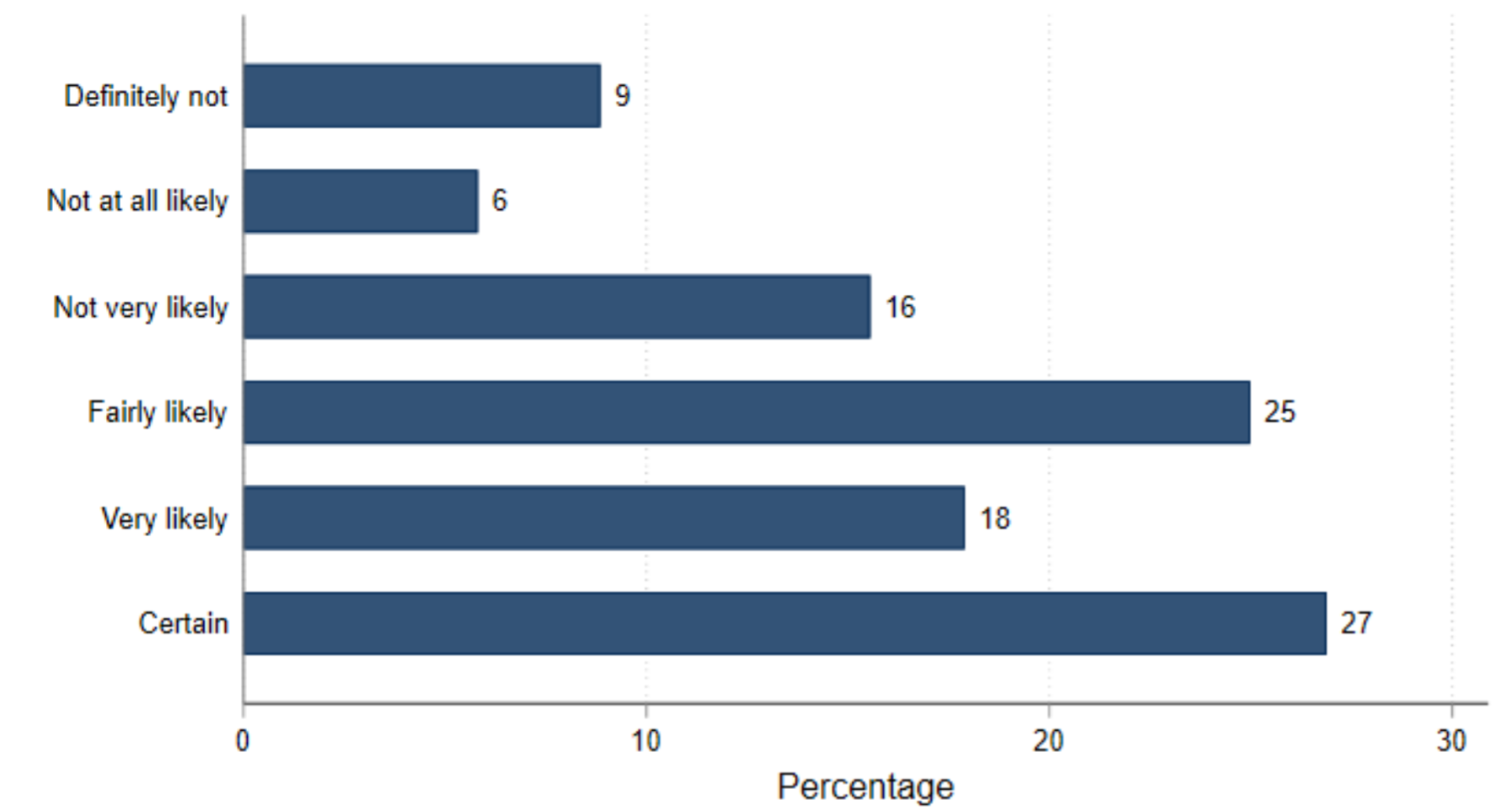

Respondents were asked, “If a coronavirus vaccine became available and was offered to you, how likely or unlikely would you personally be to get the vaccine?”. While the majority (70%) of young people say they are likely or certain to get the vaccine, this includes 25% who are only ‘fairly’ likely. Worryingly, nearly a third express some degree of vaccine hesitancy, saying that they either definitely won’t get the vaccine (9%) or are that they are not likely to do so (22%).

Figure 1: Almost one-third of young people have doubts about taking a COVID vaccine

Weighted for non-response. Source: UCL CEPEO/LSE COVID-19 survey 2020-21. Sample = 3,931

Although there are differences in question wording and response alternatives, this represents a substantially higher level of vaccine hesitancy than a recent Office for National Statistics (ONS) survey of UK adults, which found just 6% expressing vaccine hesitancy, although this rose to 15% amongst 16 to 29 year olds.

Differences in vaccine hesitancy across groups

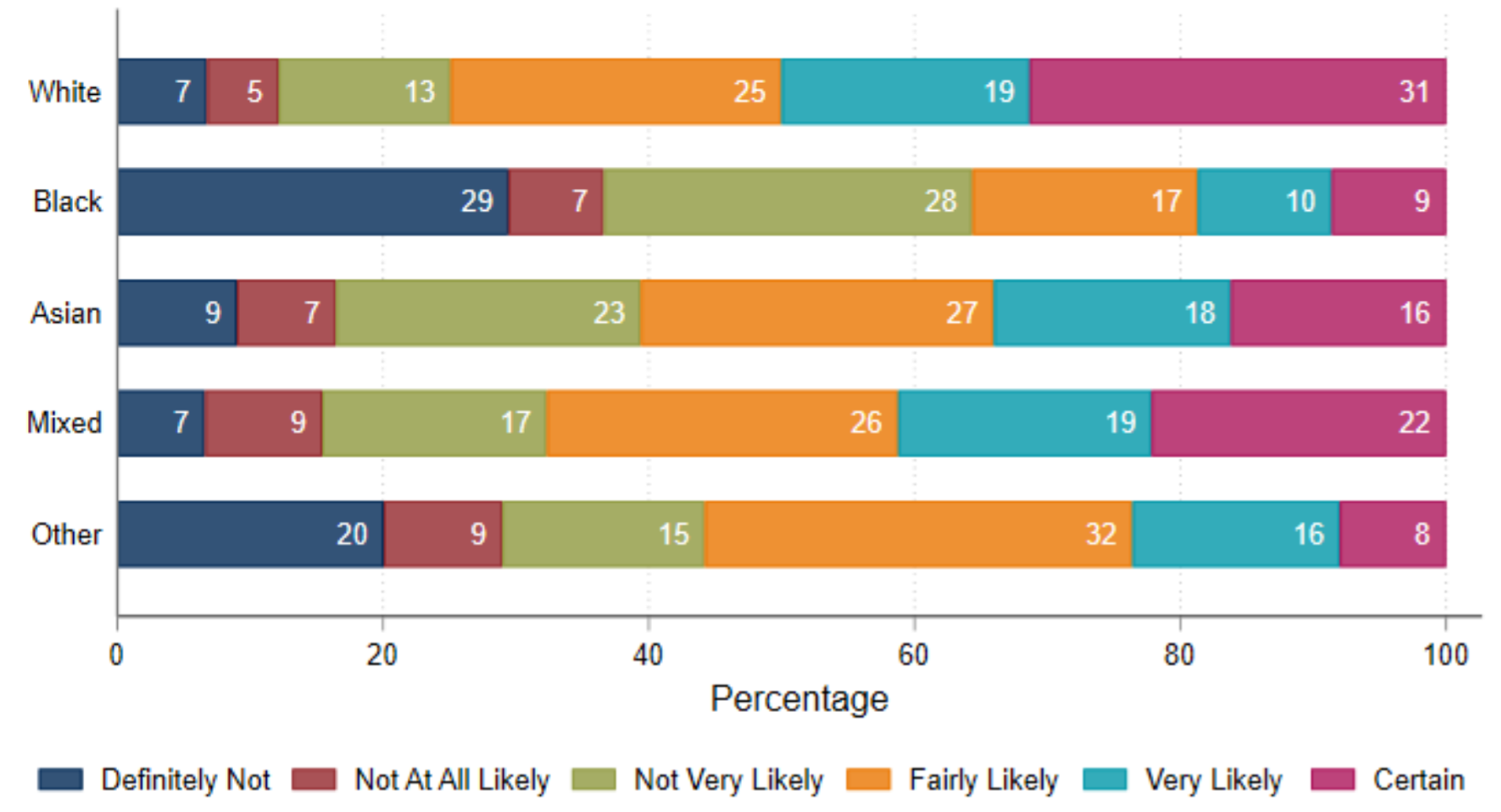

We found little variation in hesitancy between male and female respondents (32% female and 29% male), or between school year groups. However, as can be seen in the chart below, there were substantial differences in vaccine hesitancy between ethnic groups. Black young people are considerably more hesitant about getting the vaccine than other ethnic groups, with nearly two thirds (64%) expressing hesitancy compared to just a quarter (25%) of those who self-identified as White. Young people who identified as mixed race or Asian expressed levels of hesitancy between these extremes, with a third (33%) of mixed race and 39% of Asian young people expressing vaccine hesitancy. This ordering matches the findings for ethnic group differences in the ONS survey, where 44% of Black adults expressed vaccine hesitancy compared to just 8% of White adults.

Figure 2: There is noticeably higher vaccine hesitancy among Black young people

Weighted for non-response. Source: UCL CEPEO/LSE COVID-19 survey 2020-21. Sample = 3,779

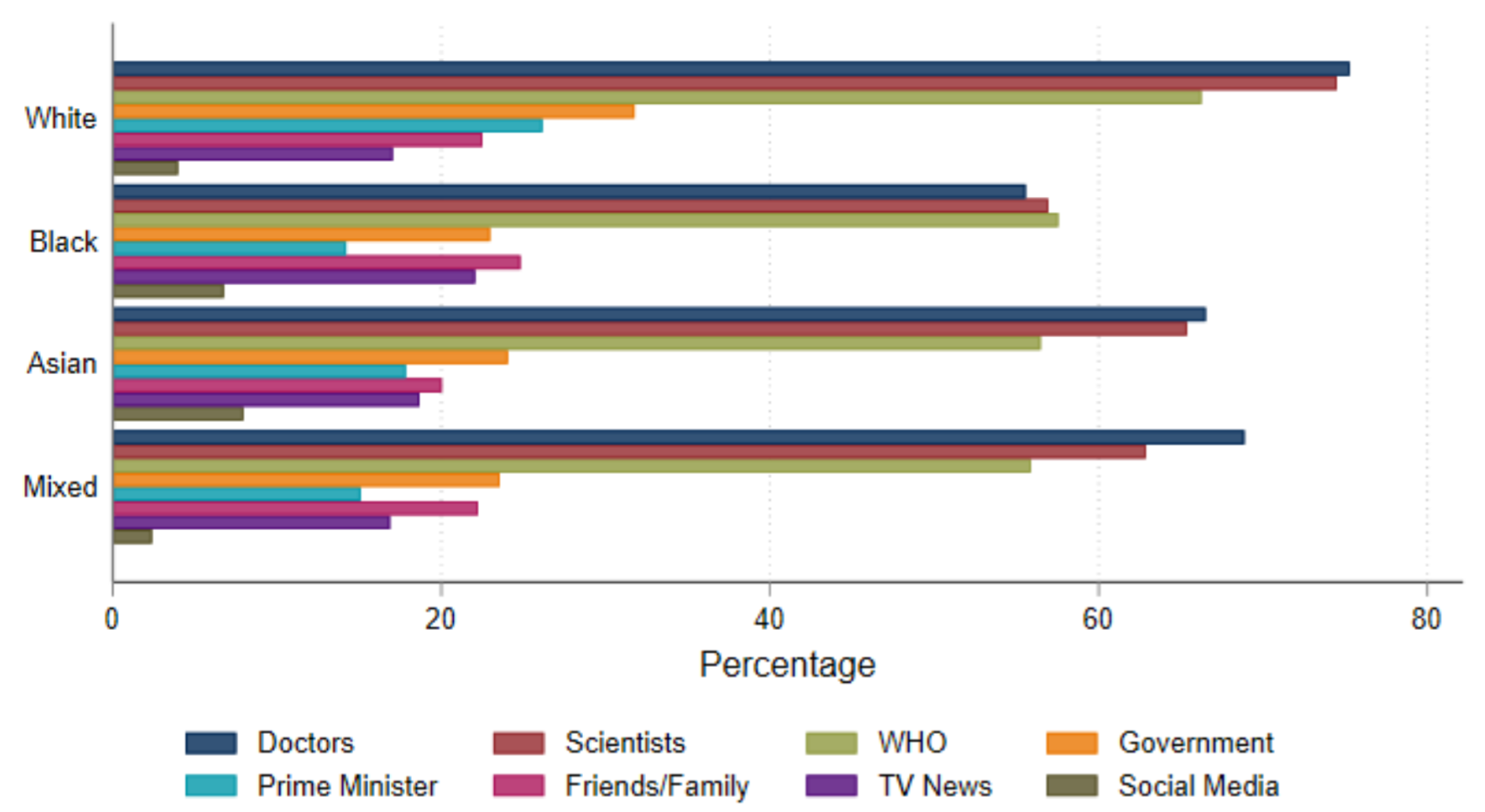

Respondents were asked to state their level of trust in the information provided by a range of different actors in the pandemic. The chart below shows wide variability in expressed levels of trust across different sources between ethnic groups, most notably between Black young people and those from other ethnic groups. Young people self-identifying as Black were considerably less likely to trust information from doctors, scientists, the WHO, and politicians, and more likely to trust information from friends and family than those from other ethnic groups—although in terms of overall levels, doctors, scientists and the WHO are most trusted by all groups. Encouragingly, only 5% of young people say they trust information from social media, a figure which was consistently low across ethnic groups.

Figure 3: Significantly different trusted sources among Black young people

Weighted for non-response. Source: UCL CEPEO/LSE COVID-19 survey 2020-21. Sample = 3,559

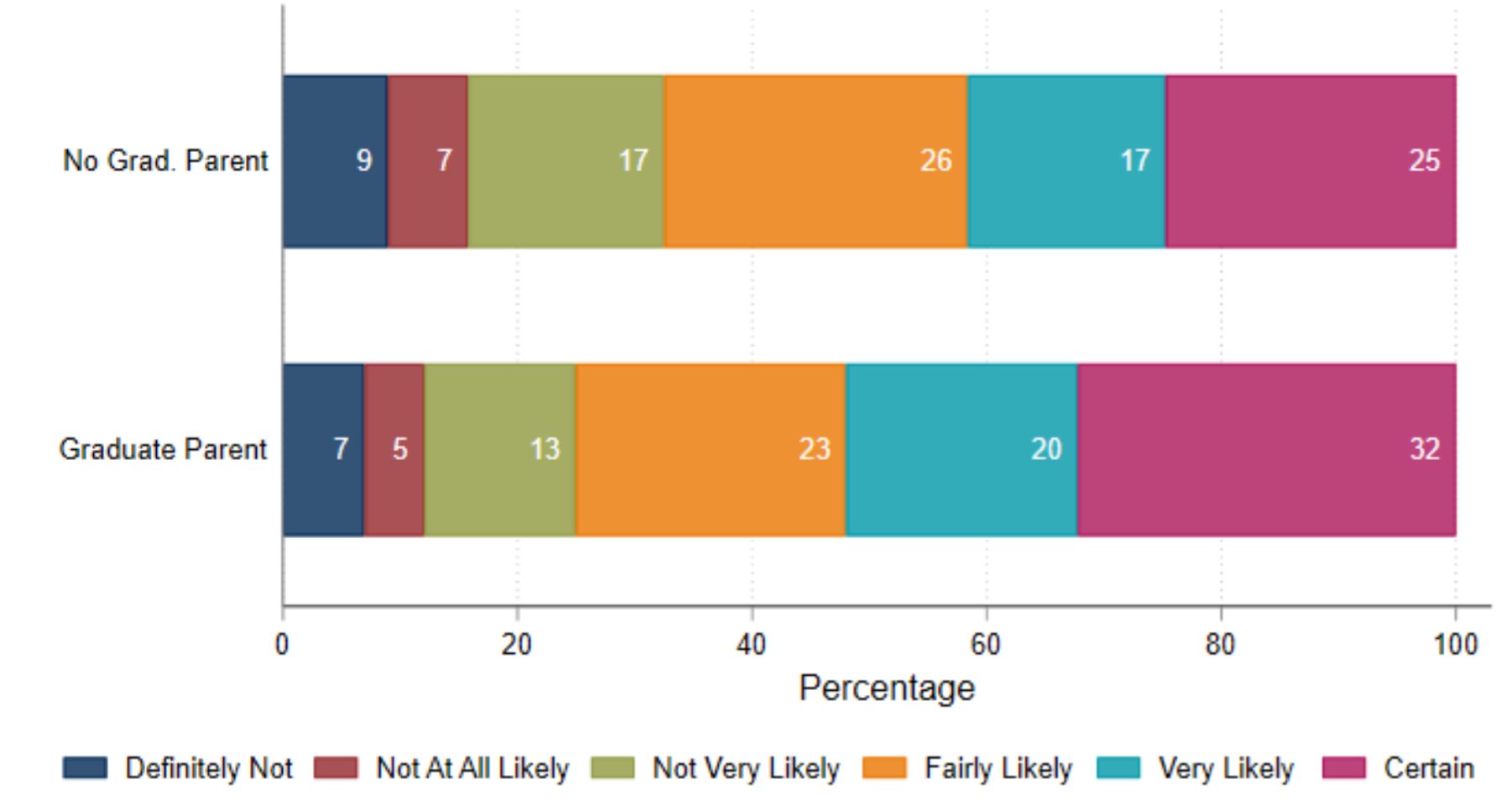

We also find evidence of a small social class gradient in vaccine hesitancy, with a quarter (25%) of young people from families with at least one parent with a university degree expressing vaccine hesitancy, compared to a third (33%) of young people with no graduate parent.

Figure 4: Higher vaccine hesitancy among those with non-graduate parents

Weighted for non-response. Source: UCL CEPEO/LSE COVID-19 survey 2020-21. Sample = 3,545

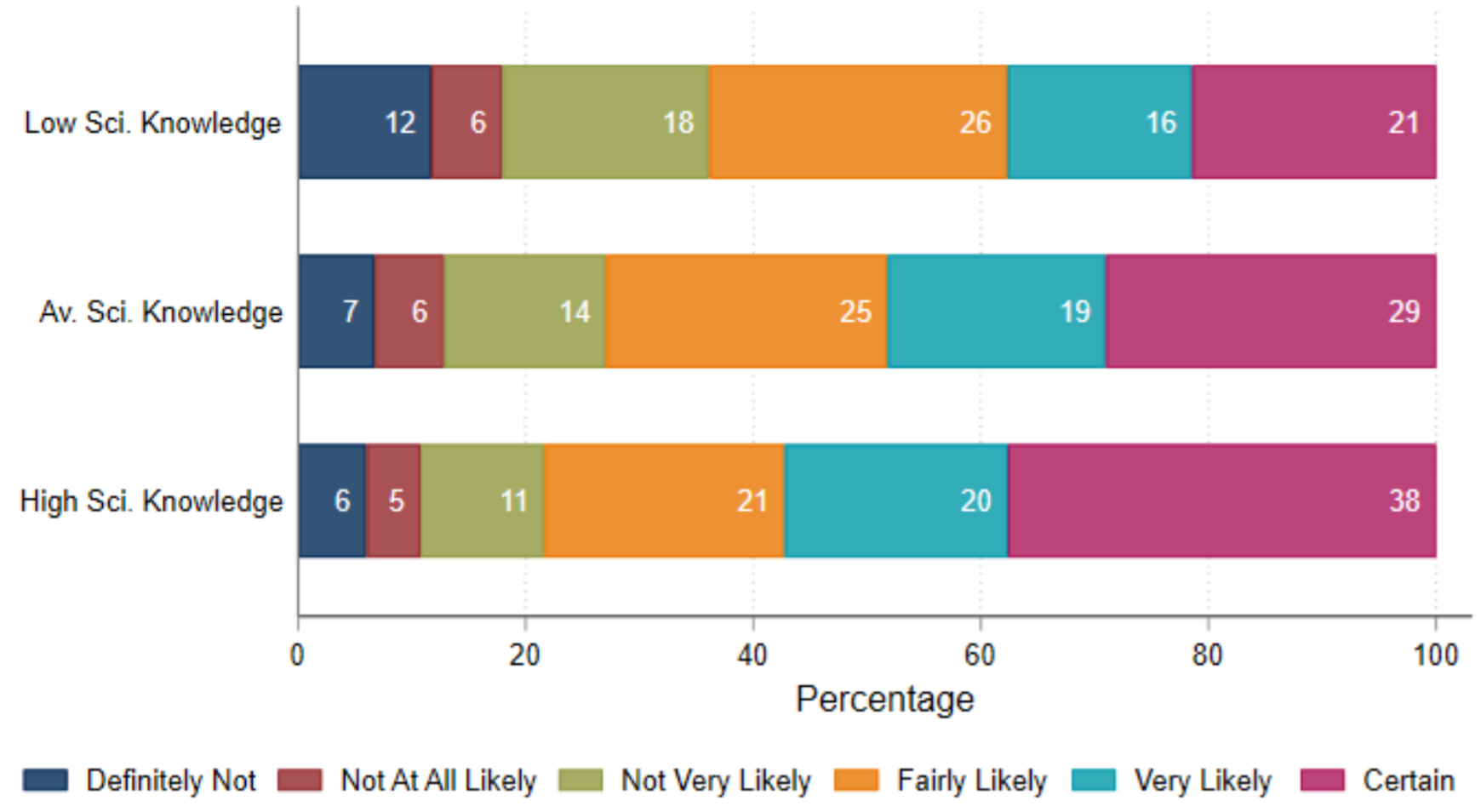

We can also compare levels of vaccine hesitancy according to how young people scored on a short test of factual knowledge about science. Vaccine hesitancy was notably higher among respondents who were categorised as ‘low’ in scientific knowledge (36%) compared to those with ‘average’ (28%), and ‘high’ (22%) scientific knowledge. This suggests that vaccine hesitancy may be related, in part, to the extent to which young people are able to understand the underlying science of viral infection and inoculation and to reject pseudoscientific claims and conspiracy theories.

Figure 5: Vaccine hesitancy is higher among those with less scientific knowledge

Weighted for non-response. Source: UCL CEPEO/LSE COVID-19 survey 2020-21. Sample = 3,774

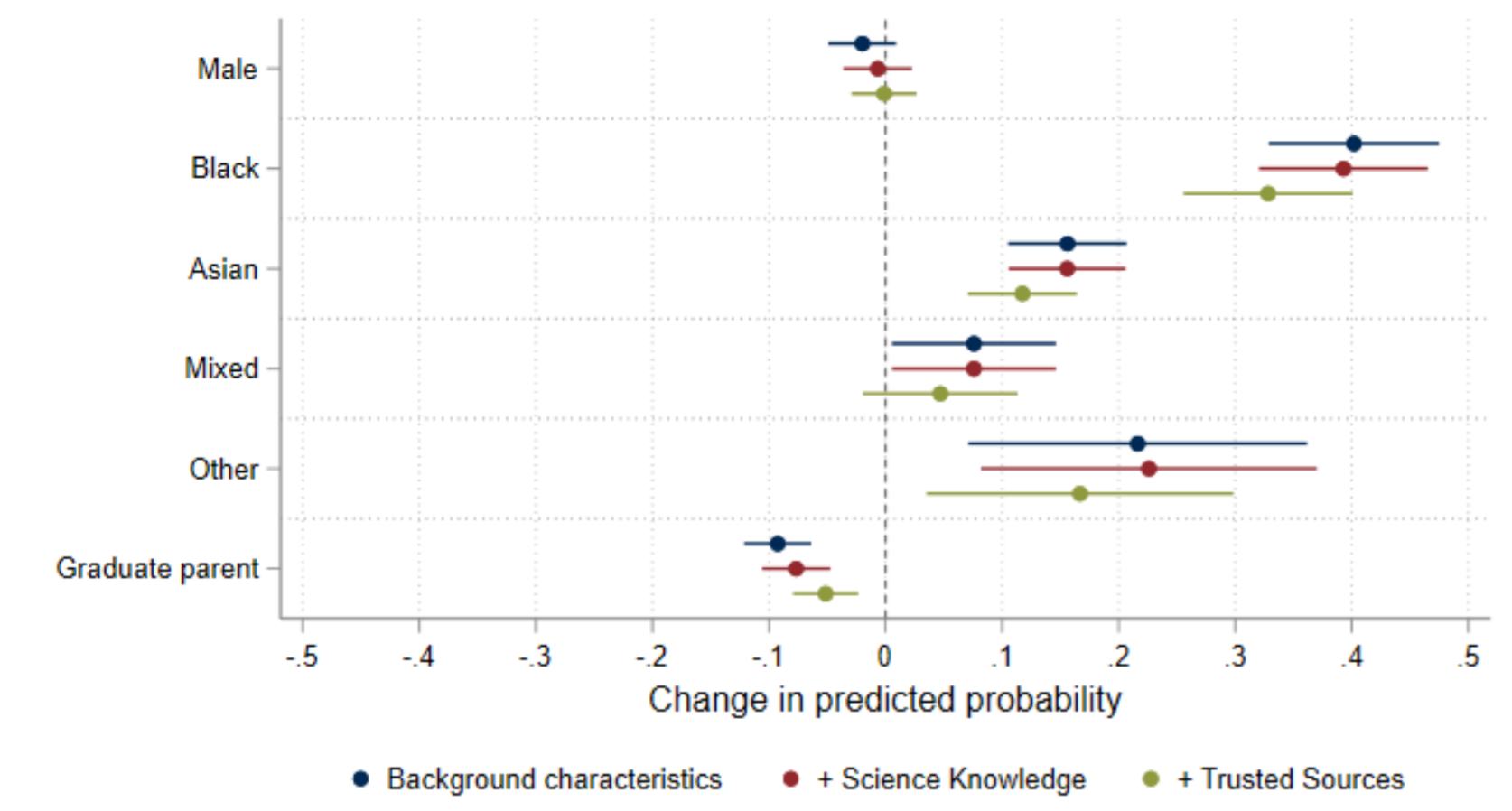

How much are differences in vaccine hesitancy just picking up underlying variation between ethnic groups in scientific knowledge and broader levels of trust? In the chart below, we compare raw differences in vaccine hesitancy for young people from the same ethnic group, sex, and graduate parent status (blue plots) with differences after taking account of differences in scientific knowledge and levels of trust in different sources of information about coronavirus. These potential drivers of vaccine hesitancy do account for some of the differences between ethnic and social class groups. While Black young people are around 40 percentage points more likely to express vaccine hesitancy than their White counterparts, this is reduced to 33 points when comparing Black and White young people with similar levels of scientific knowledge and (in particular) levels of trust in sources of coronavirus information.

Figure 6: Associations with vaccine hesitancy

Marginal probabilities from logistic regression model, also including year group categorical covariates. Weighted for non-response. Source: UCL CEPEO/LSE COVID-19 survey 2020-21. Sample = 3,297

Our survey shows high levels of vaccine hesitancy amongst young people in England, which should be a cause for concern given the likely need to vaccinate this group later in the year. We also find substantial differences in hesitancy between ethnic groups, mirroring those found in the adult population, with ethnic minorities – and Black young people in particular – saying they are unlikely or certain not to be vaccinated. These differences seem to be related to the levels of trust young people have in different sources of information about coronavirus, with young Black people more likely to trust information from friends and family and less likely to trust health professionals and politicians.

There are reasons to think that actual vaccine take-up may be higher than these findings suggest. First, Professor Ben Ansell and colleagues have found a decrease in hesitancy amongst adults between October and February, a trend which was also evident in the recent ONS survey. It seems that hesitancy is declining amongst adults as the vaccine programme is successfully rolled out with no signs of adverse effects, and this trend may also be evident amongst young people. Given that parental consent will be required for vaccination for under-18s, it may be the case that parental hesitancy is just as important for take-up as what is expressed by young people themselves.

There may also have been some uncertainty in our respondents’ minds about what is meant by ‘being offered’ the vaccine, given there were no vaccines authorised for young people at the time the survey was conducted, and no official timetable for immunisation of this group. Nonetheless, this uncertainty cannot explain the large differences we see across groups, particularly those between White young people and those from ethnic minority groups. If the vaccine rollout is to be extended to younger age groups, we will face a considerable challenge in tackling this hesitancy.

Methodology

The UKRI COVID-19 funded UCL CEPEO / LSE survey records information from a sample of 4,255 respondents, a subset of the 6,409 respondents who consented to recontact as part of the Wellcome Trust Science Education Tracker (SET) 2019 survey. The SET study was commissioned by Wellcome with additional funding from the Department for Education (DfE), UKRI, and the Royal Society. The original sample was a random sample of state school pupils in England, drawn from the National Pupil Database (NPD) and Individualised Learner Record (ILR). To correct for potentially systematic patterns of respondent attrition, non-response weights were calculated and applied to all analyses, aligning the sample profile with that of the original survey and the profile of young people in England.

Our final sample consists of 2,873 (76%) White, 208 (6%) Black, 452 (12%) Asian, 196 (5%) Mixed, and 50 (1%) Other ethnic groups. The Asian group contains respondents who self-identified as Asian British, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Chinese or ‘other Asian’.

We have not yet linked the survey data to the National Pupil Database and Individualised Learner Records, which will enable us to use an indicator of eligibility for free school meals and the Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index. Currently we use parent graduate status as a proxy for socio-economic status.

There were ten items in the scientific knowledge quiz: ‘low’ knowledge equated to a score of 5 or less, ‘average’ knowledge to a score of 6 to 8, and ‘high’ knowledge to a score of 9 or 10. Note that this test was administered in the previous (2019) wave of the survey.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

Hello,

I am studying the Masters Course in Global Health at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and am currently engaged in an assignment which involves looking into vaccine hesitancy in the younger population. Please can you inform me if the UCL CEPEO/LSE COVID-19 survey 2020-21 has been published, and if so, where I can find it?

I am particularly interested to know how the sample size was calculated, the complete version of the questionnaire, and how ethical issues were addressed considering some participants were only 13 years of age.

Thanking you.

Sincerely yours

Subroto Chatterji

Hi Subroto

It’s part of a larger study on the impact of lockdown on kids’ education – the full report isn’t out yet. Have you seen the UCL CEPEO blog? https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/cepeo/