On World Intellectual Property Day, 26 April, Siva Thambisetty (LSE) explains why she will not be celebrating. The controversy over suspending COVID vaccine patents is just the latest example of acute misalignment and injustices driven by current IP law. Far from being an unmistakable force for good, she argues, patents reward certain kinds of creativity over others and privilege corporate power at the expense of those who cannot afford to defend their rights and assert their contribution.

Three million have died — with many more to come — and only 0.2% of those in developing countries have so far been vaccinated. Yet still we give a platform to those who think it is too ‘radical’ to suspend patents. The discomfiting truth of the matter is that the patent system is functioning exactly as it was set up to function, which is why it has been left to scholars to explain why and how we need to make the technology more accessible — even as economists, former world leaders and EU lawmakers issue calls to ‘break the patents’ on COVID vaccines and ‘support the patent waiver’.

Intellectual property (IP) has its place, and there are some good reasons to continue with an IP system that is fit for purpose, but also many reasons not to. None of what follows are reasons for an outright rejection of all IP laws, but they are symptoms of a diseased system, and stem from highly questionable premises grounded in a flawed view of human nature.

IP creates artificial scarcity so that the holder of that right can generate returns from it. This device plays an important function — it gives you an incentive to to come up with something — an idea, a tune, a novel, a pill — and helps protect it as yours when you do. Research tells us that this incentive may be necessary for routine tasks requiring some creativity. But higher order creativity that requires sophisticated cognitive functions do not respond to incentives in the same way. A system that assumes that all creativity and innovation is best incentivised by intellectual property rights (IPRs) is in effect hard-selling us a particular and limited version of creativity.

There are three main kinds of IP rights: patents, copyright and trademarks. Historically and legally the reasons to establish these rights are different, yet they all suffer from overreach and blind spots that threaten our ability to stay in charge of our autonomous, creative selves. So here are ten problems with ‘world intellectual property’ to explain why I am not celebrating today.

1. It puts muscular meritocracy ahead of people

Access to affordable patented medicines is a longstanding problem, and the pandemic has magnified it. We need better ways to incentivise ethical and humanitarian innovation. When we focus on commercial benefits, we forget to amplify other, more human drivers. There is the idea that by creating something that may be protected by intellectual property, one has created something of value and therefore the individual herself is morally entitled to all extractive expressions of that value. Success in IP (which could be as trivial as gaining a patent, or producing music that can be traded) is often equated with moral deserving. This simple yet pernicious equation has converted IP into a muscular form of meritocracy that privileges narratives of individual initiative and mastery over good fortune, hubris over humility, and outcome over the pleasure of labour.

This version of human striving creates a culture where individual responsibility and deserving is everything. The inventors of the AstraZeneca vaccine at the University of Oxford, for instance, are heralded as inventors deserving of a patent. But the infrastructure of the university and the work of countless post-docs and researchers has made the vaccine possible. Over time, this view not only sanctifies winners and denigrates losers, it tramples on providential or communitarian labour and inputs.

Intellectual work is as much the product of fortune and fate as anything else. Deeply embedded notions of merit, moral deserving and value threaten our self-image at a time when our most fundamental challenges — like climate change, food security, and pandemic resilience — are civilisational and collective in nature.

2. It undermines imitative learning

Until a few decades ago, there was no ‘world IP’. Intellectual property was designed as a territorial right, for individual nations to decide tailor-made incentives for local industries depending on the maturity of the industry. Imitation is a powerful means of learning. In the early days of an industry, copying and free riding are a significant driver that can lead eventually to innovative local industries. For instance, many countries in the late 1970s and 1980s did not have patent protection for chemical products. This allowed them to thrive by reverse-engineering and copying new information from wherever it existed, eventually growing innovative pharmaceutical industries. ‘World IP’ pushed through global trade treaties means the ability to organically develop local industries does not currently exist for scores of developing and least developed countries. The harmonisation of intellectual property rights makes assumptions about the state of preparedness of economies to use monopoly rights, and denies countries the time they need to learn by imitation.

3. It creates an unequal fight between public and private realms

IP depletes the source material we all use to be creative, because IP holders have been able to incrementally extend the scope of their rights, often relying on ambiguous interpretations of the law to push extractive agendas. Newspaper headlines, musical riffs and fragments that are such an important part of subconscious creativity may be exclusively monopolised. Critically, property holders are more keen to protect their rights than the public are to defend their right to continue to access the public domain. This skews our ability to preserve the public domain, even where the law is not so clear about who owns what. Consider recipes, trends in fashion, humour and comedy, good writing; they all depend on source material being freely available for everyone to build on.

4. It perpetuates ‘measurable’ creativity

More IP does not mean more creativity or more innovation. The vast proportion of patents that are granted protect inventions that will never make it to the marketplace. Yet no one can use the information in those patents for the duration of the patent right — 20 years. Patents or patent applications are tenuous markers of innovation, but nonetheless are central to innovation policy making.

5. It is unsuited to a digital age

IP does not easily map on to patterns of creativity in the digital age. Think of the ease of remixing and rehashing, the way we can cut and paste small bits of music or film or text to often create something magical and entertaining. Personal use, or use for non-commercial purposes, is constantly under threat by over-zealous IP holders who work on the assumption that anything of value must be propertised. This leads to fragmented ownership of ideas, knowledge and information. When in doubt, most of us would rather not infringe intellectual property rights than take the chance. It does not help that the law is often ambiguous on what amounts to infringement.

6. It compounds inequality

IPRs help make money, but often in ways that favour large aggregated rights holders like publishers and music collection societies at the cost of individual creators, song writers, and authors. Litigation is extremely expensive. Unless you can make credible threats to litigate and spend money on lawyers and the courts, your IP right remains a protection in name only.

7. It is an international tool of exclusion

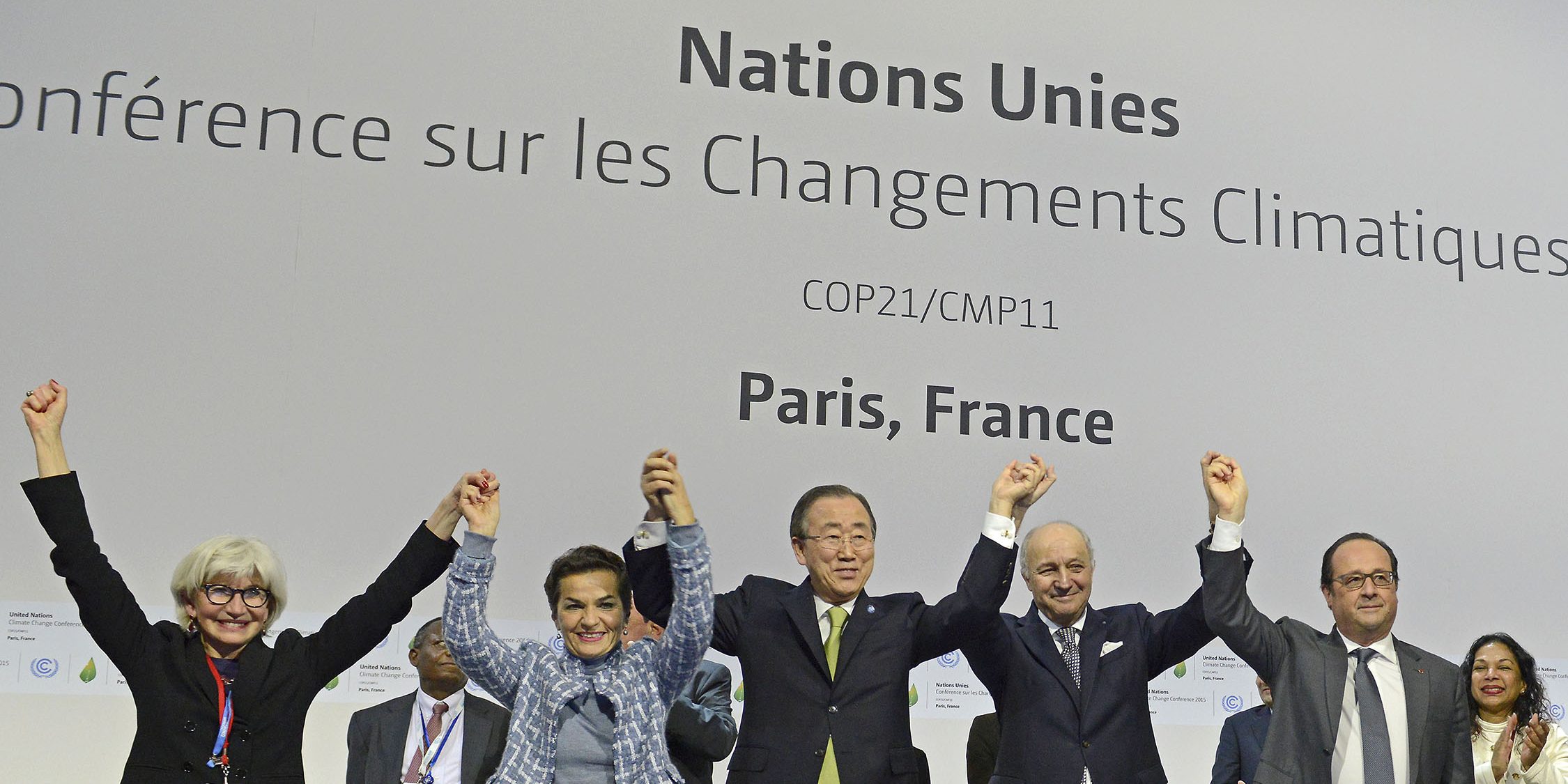

Many international norms of justice are useless and ineffective because IP is now a matter of foreign policy. The Paris Agreement could not reach a consensus on climate related technology transfer and intellectual property, so it was left out of the Agreement. The new UN oceans treaty is also under threat if we cannot agree a fair way to distribute benefits from marine genetic resources of the deep sea — some of which could be productive sources of anti-virals. In a global world, IP is the handmaiden of trade, capital and power.

8. It appropriates hidden labour

Many of our closest experiences of IP come from brand value, or public consumption of entertainment, and there is a great deal of hidden labour in public culture. Consumers who participate and amplify different meanings contribute enormously to the success of a brand. For brand owners to claim that they own much of the value of what was created should feel unfair, but it often doesn’t because our labour is atomised and appropriated.

9. It devalues social innovation

Intellectual property rights do little to acknowledge the work of previous inventors and creators. Imagine a child is trapped under a car, and four people are unable to lift it. A fifth person arrives and the car moves. The child escapes unhurt. Who would you give the credit of saving the child — all five, or just the fifth person? Many IPRs do not acknowledge the contribution of the four people, but give a ‘winner takes all’ reward to the fifth person, thus undervaluing the sociality of innovation.

10. It undermines traditional knowledge

The patent system favours particular forms of knowledge over others, acting as a gatekeeper and curator of vast quantities of scientific and technical knowledge and information. Unfortunately it has no way to grant equivalence to traditional forms of knowledge. There are many ways of knowing something — if we discover that ginger has anti-viral properties that can dampen the effect of COVID, we might say the reason it does so is ‘the spirit in the root’, or you could say the technically described, active ingredient in ginger has an anti-viral effect. The patent system will only allow someone who uses the latter language to claim an exclusive right to use ginger as an anti-viral. This misalignment has led to communities losing patrimony over traditional forms of knowledge, taken over by reductive ways of controlling, owning and disseminating information.

So by all means raise a glass today, but not to ‘World IP’. Spare a thought instead for the diversity of all the creators and innovators out there —scientists working towards treatments and vaccines; the ingenuity of many in marginalised communities who hack their way to a better life; and those communities who steward the biodiversity that now contributes to many of our pharmaceuticals.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

Wonderful.

On point. Well, IP is the major reason for the setback of vaccination drive in India.

A compelling piece, Siva!