In Pakistan, most women give birth within two years of their marriage. Mazhar Mughal (ESC Pau Business School) and Rashid Javed (Westminster International University) discuss the likely impact of lockdowns and the ban on marriage ceremonies in 2020 on fertility rates.

One of the lesser-known results of the pandemic has been its impact on marriage and childbirth. These demographic consequences are particularly important in developing countries—where birth rates remain high, marriage is nearly universal, and almost all childbearing takes place within marriage. COVID infection normally has little effect on fertility. The overwhelming majority of those who have died due to coronavirus have been elderly, often with one or more comorbidities. However, the impact of lockdowns on marriage and fertility may well prove to be substantial.

In a recent study, we discuss the delay in marriage caused by the ban on public gatherings and the closure of wedding halls during the first lockdown imposed by the government of Pakistan. During the first lockdown, which began on 13 March 2020, all educational institutions and public gathering places, including marriage halls and sport stadiums, were closed and public events were cancelled. Though some restrictions were relaxed on 9 May, public gatherings remain prohibited until 14 September that year. The closure of marriage halls, banquets and marquees during this six-month period led to the postponement or cancellation of ceremonies during the prime wedding season. We analysed the possible impact on fertility of the resulting delay in marriages, and report some preliminary findings.

The data used in this paper come from the latest round of Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) carried out in 2017-18. The survey covered 15,068 women from 14,540 households with a total of 50,495 corresponding children.

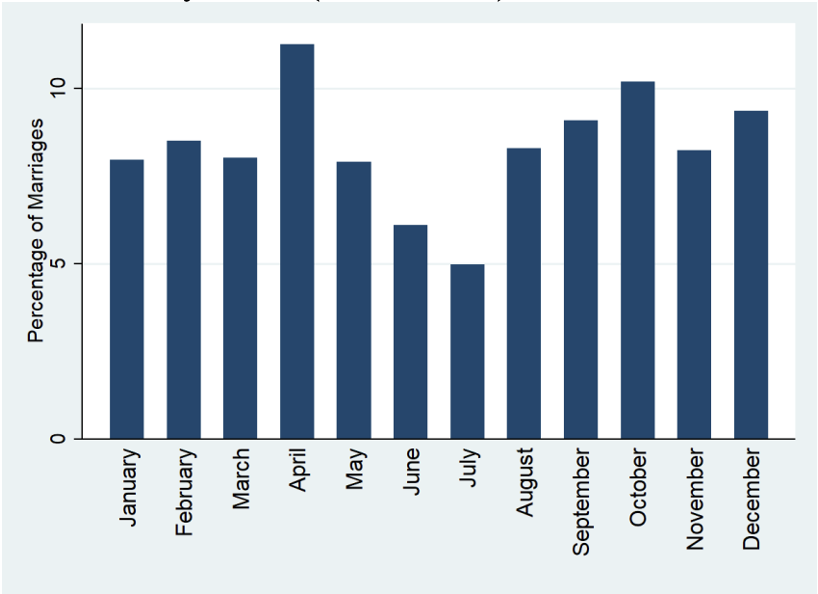

Figure 1: Marriage distribution by month (2013–17)

Source: Authors’ calculations using PDHS 2017-18

The bulk of marriages in Pakistan take place in spring and autumn. Figure 1 shows the distribution by months of marriage for 3,311 women who married between 2013 and 2017. Along with seasonal variations, Pakistan’s marriage calendar shows changing trends due to the shifting of the Hijri calendar. Pakistan’s majority Muslim population usually do not celebrate marriages during the months of Muharram (the first month) and Ramadhan (the ninth month). The Islamic calendar is based on lunar observations and is about eleven days shorter than the solar calendar, so events based on the lunar calendar drift through the seasons. In 2013, the month of Ramadhan started on 11 July. In 2017, it began 44 days earlier on 27 May.

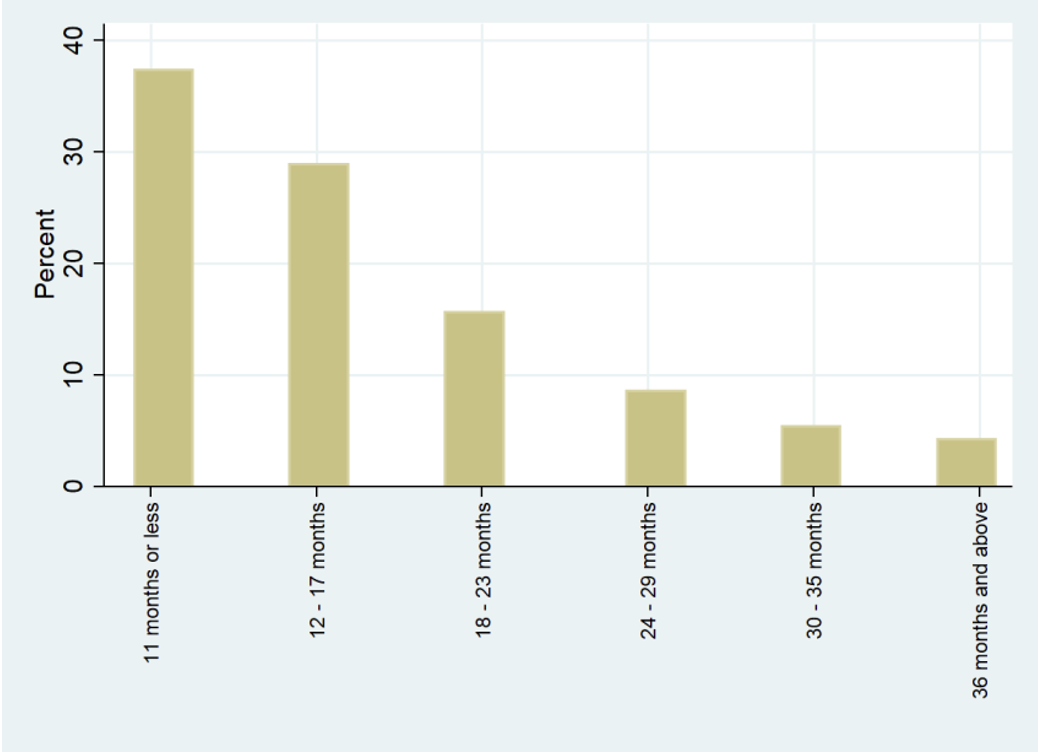

Figure 2: Interval between marriage and first birth (2013–17)

Source: Authors’ calculations using PDHS 2017-18

Our back-of-the-envelope calculations based on the monthly mean of marriages from 2013 to 2017 show that the closure of marriage halls during 2020 will have affected nearly half (47.45 percent) of the marriages that were to take place during the year. This involuntary delay, which may range from a few days at the minimum to six months or more, is bound to have a non-negligible impact on subsequent fertility. In Pakistan, childbearing begins soon after marriage, and about 37 percent of Pakistani married women give birth to their first child within twelve months of marriage (Figure 2). The number of babies born within the first year of marriage corresponds to about 6.6 percent of the total births. Around 400,000 births may therefore be delayed due to COVID-related marriage postponements .

This impact may, however, prove to be temporary, as these delayed births can be ‘recuperated’ in the second year of marriage. This could result in a minor baby bump as newly-wed couples move to make up for lost time. There is also some anecdotal evidence suggesting that weddings did take place during summer 2020 with limited guests, as many families consider it undesirable to postpone a wedding once the match has been made.

However, there are other reasons to suggest that the pandemic and its lockdowns may have affected new marriages and fertility. Inordinate delays, the postponement of wedding arrangements and an atmosphere of stress and fear can exacerbate tensions which could ultimately cause engagement to break down. Another reason for the postponement of marriages, especially those involving participants from overseas, might be the travel difficulties that guests or even the marrying couple faced during the spring and summer of 2020. During this period, travel to Pakistan from the major destinations of Pakistani migrants was far below average. Consequently, many marriages had to be put off.

The cumulative effect of delayed marriages could be a significant delay in childbirth. This impact may, however, be dampened if existing couples change their behaviour. Lockdown might lead to more sex as a result of couples being cloistered together; but it may have a negative effect on their childbearing intentions, given the environment of uncertainty and fears about the future. Sex and childbearing may also suffer if there is violence or conflict in the relationship. Exactly how significant the impact on fertility has been will soon become apparent.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. It is based on Mughal M, Javed R. Perturbed nuptiality, delayed fertility: childbirth effects of Covid19. Journal of Population Research. 2021.