What is the best response to combat the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic? Although some success stories and key lessons are emerging (early response, large-scale testing, effective containment), countries have adopted a strikingly wide array of strategies. Free media can explain part of the difference in country responses to COVID-19, write Tim Besley and Sacha Dray (LSE). Countries with free media are more truthful in counting COVID-19 deaths and implement more efficient and responsive lockdowns. Free and independent media allow citizens to be better informed about the pandemic, reduce misinformation, and make governments more accountable, they argue.

There are good reasons to think that the media is playing a crucial role in affecting how governments are informing the public about COVID-19 and how a country responds to an outbreak. Having an independent press can serve to keep governments accountable and avoid underreporting of COVID-19 deaths. By making citizens better informed, free media can also coordinate behaviour and improve compliance with lockdown measures. Studying the responsiveness to COVID-19 gives a unique opportunity to learn about how governments react to a global shock over a fairly short period of time.

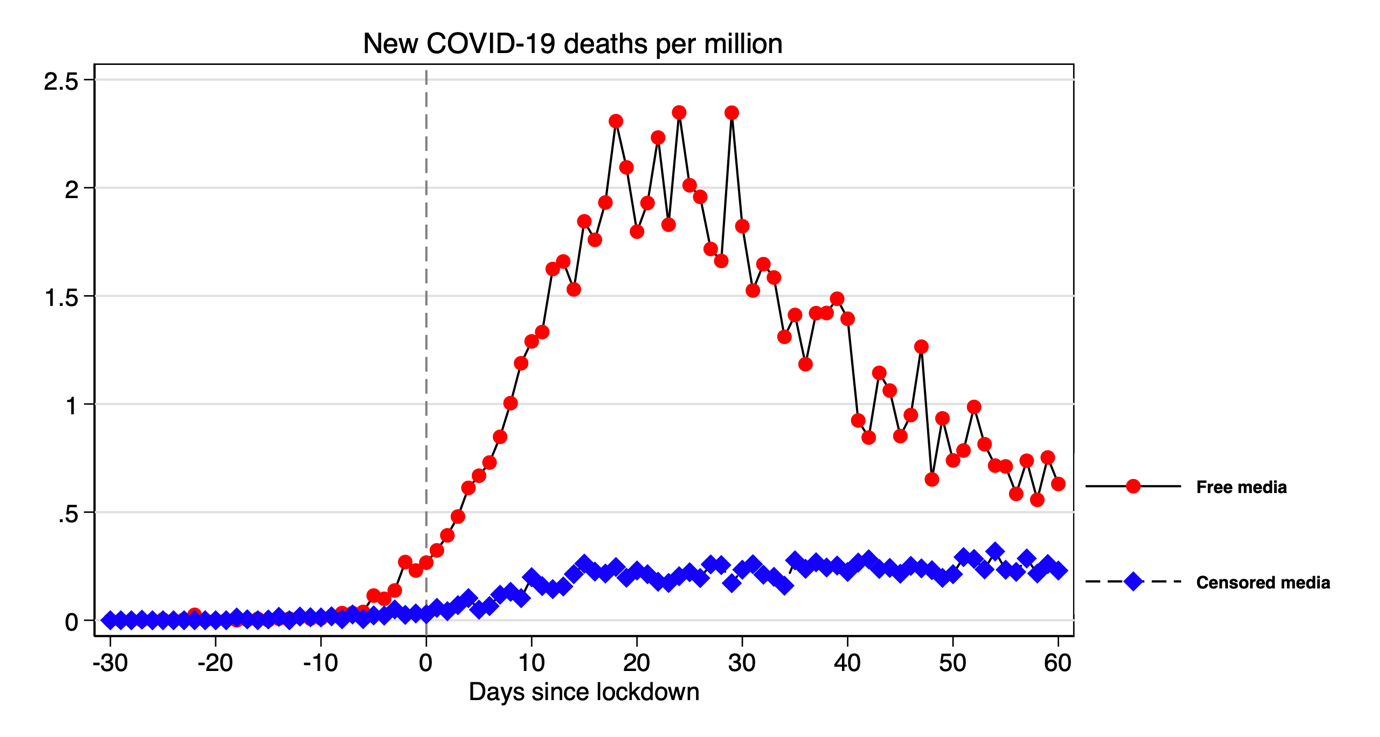

Prima facie, differences in government response to the COVID-19 pandemic appear to align with the presence of free media. Countries with free media have been more severely hit by the pandemic (105 deaths per million compared to 31 deaths per millions for censored-media countries as of July 17). However, these countries have also implemented a more rapid, effective and responsive lockdown on average. This is substantiated by Figure 1 which shows that free-media countries have locked down at the start of the increase in new deaths from COVID-19. A month into lockdown, these countries were on average able to reverse their trends in fatalities. On the contrary, while censored-media countries implemented lockdowns with a lower initial number of new COVID-19 deaths, the number of new fatalities remained flat 60 days after lockdown started.

Figure 1: Data as of July 17, 2020. Source: Authors’ calculations using the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and V-Dem [1]. See Besley and Dray (2020) for details.

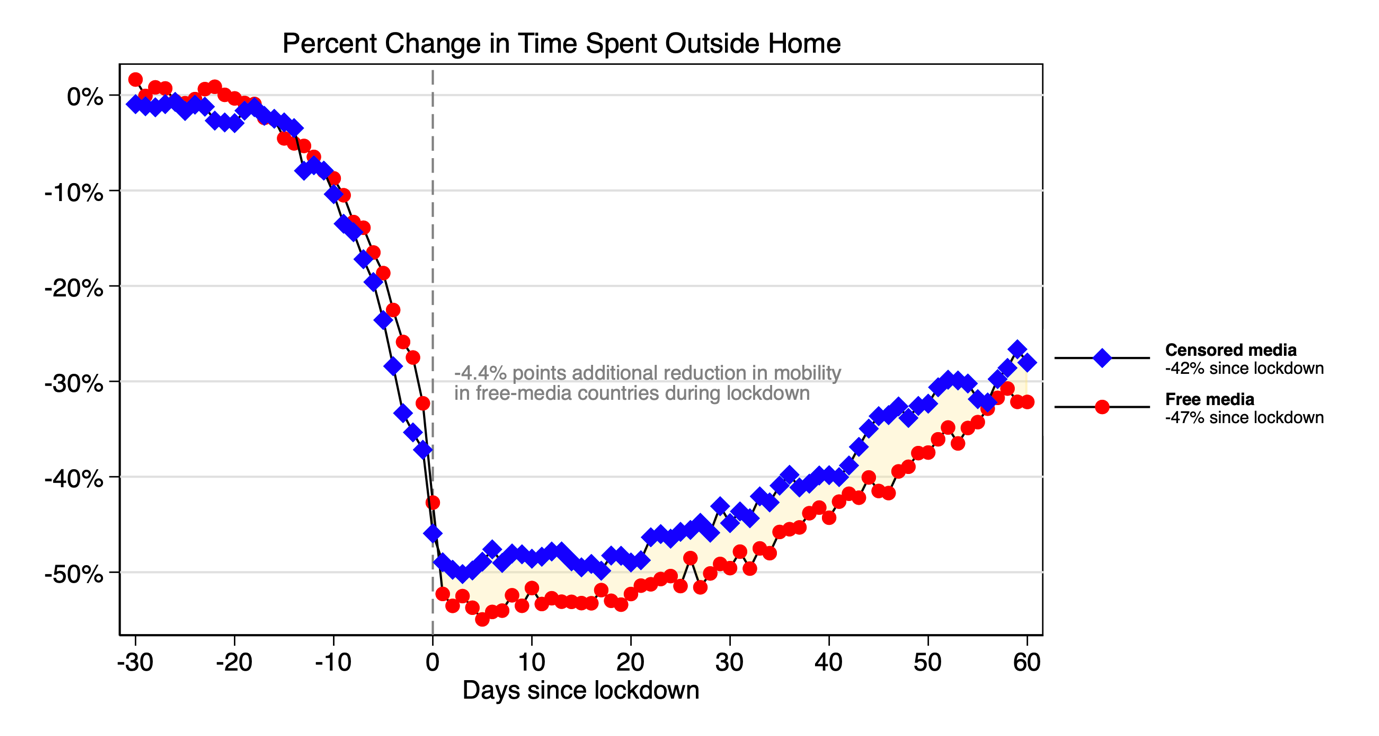

Countries with free media were also able to implement lockdowns that more effectively reduced the progression of the virus. We measure the effectiveness of lockdowns using the percentage change in time spent outside home compared to January before mobility restrictions were in place. Countries with free media reduced mobility by 47% during the first two months of lockdown compared to 42% in countries without free media. This difference appears only after lockdown started and remains constant throughout the first two months of lockdown.

Figure 2: Data as of July 17, 2020. Source: Authors’ calculations using ECDC, Google mobility reports and V-Dem. See Besley and Dray (2020) for details.

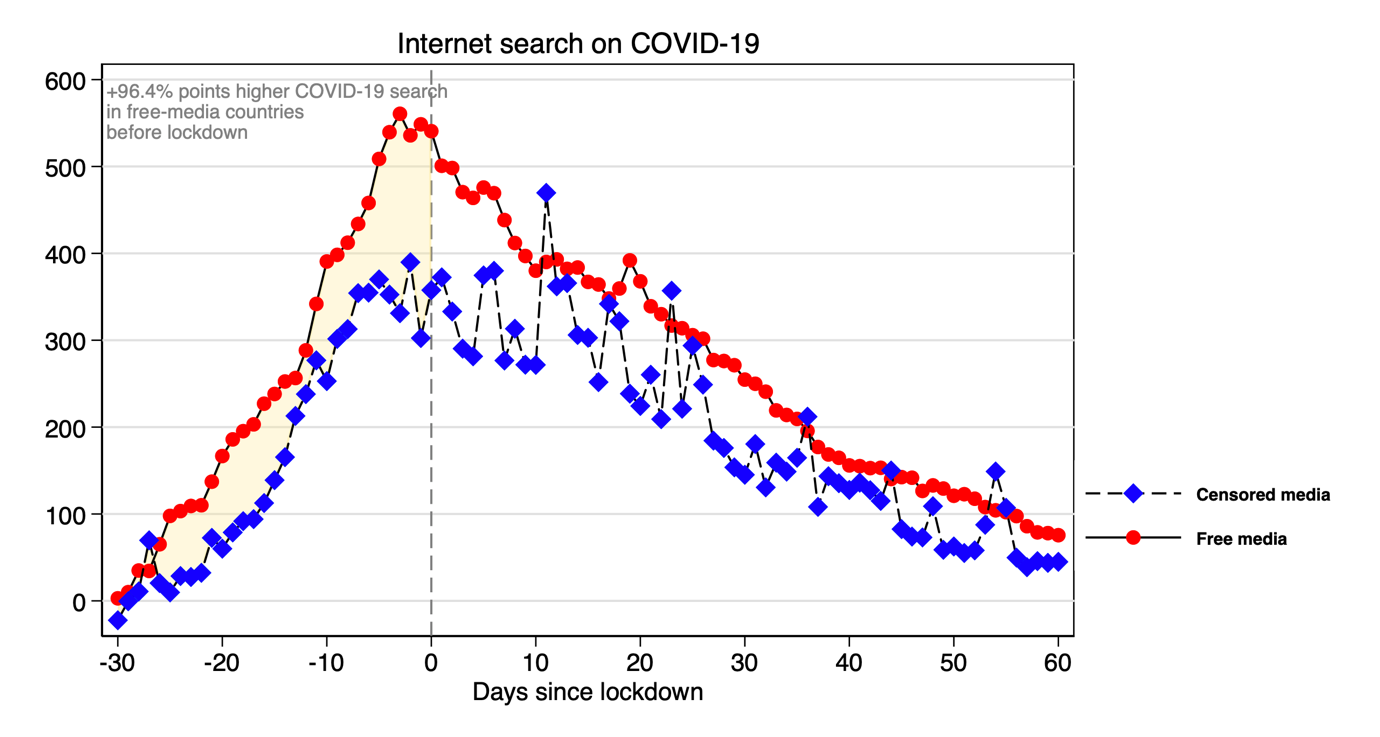

So what explains these findings? To investigate whether citizens with access to free media were better informed about the pandemic and lockdown measures, we look at patterns of internet searches around the time of lockdown. Countries with free media were doing significantly more internet searches with keywords related to COVID-19 in the month leading up to lockdown compared to censored-media countries. In the 30 days before lockdown, the increase in internet searches with references to COVID-19 were 96.4 percentage points higher in countries with free-media. On the day of lockdown, the share of internet searches for COVID-19 were more than 50% higher in free-media countries than censored-media countries, then attenuates during the lockdown. This suggests that citizens were better informed about the pandemic, which in turn lead them to comply more with public health recommendations during lockdown.

Figure 3: Data as of July 17, 2020. Source: Authors’ calculations using ECDC, Google Trends search and V-Dem. See Besley and Dray (2020) for details.

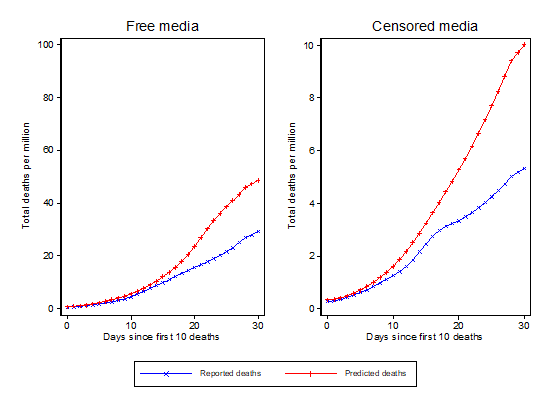

In Besley and Dray (2020), we explore in more detail how the media can influence the counting of deaths from COVID-19 and whether lockdown measures respond to information on the progression of the disease. We find evidence of under-reporting of deaths in censored-media countries. By constructing a predicted time path for the outbreak for each country using an epidemiological Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered (SIR) model, we can gauge the true severity of outbreaks in all countries and compare these predicted trends with official statistics. Our median prediction estimates a number of fatalities above the reported death toll for both censored- and free-media countries, and estimates outbreaks of lower intensity in censored-media countries. Interestingly, censored-media countries have an estimated undercounting that is 13% higher than in free-media countries. We also observe a divergence in the pattern of deaths between official counts and predictions at an earlier stage in the outbreak in censored-media countries.

Our analysis also finds that countries with free media are more responsive in their decision to lock down. This translates into a higher probability to impose a lockdown when COVID-19 deaths increase, after accounting for misreporting. Citizens in countries with free media are also more responsive to deaths when reducing their mobility. A 1% increase in COVID-19 deaths leads to an estimated reduction in mobility outside from 11 to 17% in free-media countries. We also find that differences in responsiveness cannot be explained by demographic or economic factors such as income or the age distribution in a country.

Figure 4: Reported deaths indicates the official counts of all deaths from COVID-19, predicted deaths is a prediction of fatalities from an epidemiological SIR model. See Besley and Dray (2020) for details.

These results emphasise the crucial role of a free and independent media in making citizens better informed about the pandemic, reducing misinformation, and making governments more accountable. The COVID-19 pandemic represents one of the largest public health and economic crisis since formal record-keeping began. It has caused major disruptions and has proved a significant test for governments worldwide. Lockdown policies have re-entered the policy lexicon with significant economic consequences for vulnerable groups. In places with free and active media, government policy is under constant scrutiny. It is too early to provide a proper assessment of the costs and benefits of the emergency responses taken to contain the pandemic, including lockdowns. Whichever way that debate evolves, the media can play an important role in shaping how citizens become informed about the crisis and how governments respond to it.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

1 Comments