Wherever there is a fixed budget constraint, money should be allocated to policies which give the greatest increase in wellbeing per pound of expenditure, argues Richard Layard (LSE). Even policy-makers unmoved by wellbeing as an objective should promote it because of its large positive effects on productivity, academic learning and life expectancy.

The overarching criterion

Most policy makers have multiple objectives. But in the end, they have to decide whether one policy is better than another. The decision maker must have some view about which objectives are most important. It would be much better to make this explicit by having and applying a single overarching criterion against which to judge the merit of different outcomes.

That criterion should be the wellbeing of the people. There are of course many good things – health, wealth, freedom and so on. But for each of these goods we can ask ‘Why are they good?’ and expect an answer. For example, health matters because without it people feel lousy. But if we ask ‘Why does it matter how people feel?’, we can give no answer. Yet it self-evidently matters, which is why the happiness of the people is the most obvious candidate for the overarching good.

Many policy makers have problems with the word happiness and instead prefer the term wellbeing. That is fine, provided we are clear that it is the people’s wellbeing as they themselves judge it – not as some researcher or civil servant evaluates it. In other words, we are talking about “subjective wellbeing”. The typical way of measuring this is to ask “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life these days?” (0= very dissatisfied, 10= very satisfied).

Fortunately, more and more policy-makers in the OECD and elsewhere now consider that policy should be targeted at wellbeing. In 2020 the EU Council of Ministers urged EU countries “to put people and their wellbeing at the centre of policy design”. But this approach can only be implemented if we know what causes wellbeing. Until recently there was virtually no quantitative information on this subject, but over the last 40 years a whole new science of wellbeing has developed, which now tells us enough about its causes for this to become the stated objective of policy.

Political reality

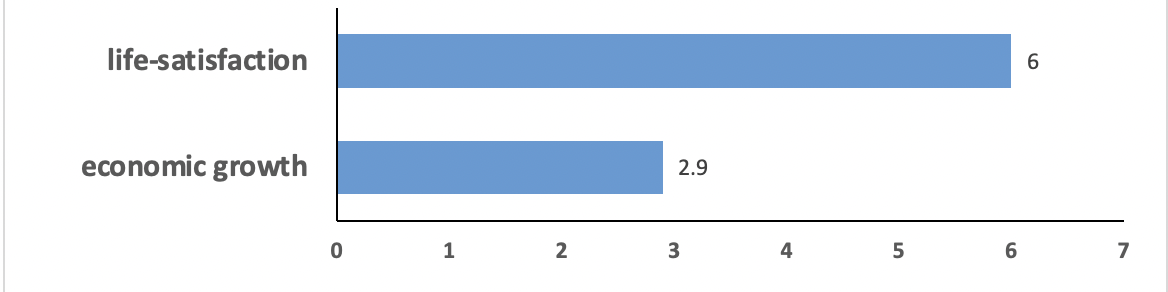

Recent research shows that the best way for a government to be re-elected is to maximise the wellbeing of the people. A study of national elections in European countries from 1974 onwards(6) found that the best predictor of the government’s vote-share in national elections was the life-satisfaction of the people.

Figure 1. Effect of life-satisfaction and economic growth on the government’s % share of the vote

(National elections in Europe since 1974)

Note: Effect of 1 standard deviation increase in each variable on the government vote share (% points) Source: Ward G. Happiness and Voting: Evidence from Four Decades of Elections in Europe. American Journal of Political Science; 2020.

Policy appraisal

So how exactly would a policy-maker choose the priorities for spending? We have to assume that the total volume of public expenditure is set by political forces. The task is therefore how to spend this total in the way that produces the most wellbeing. That means choosing those policies which produce the most wellbeing per pound spent.

This approach has been standard practice in the health field in many countries. Health states are evaluated for their quality-of-life (on a scale of 0-1) and medical treatments are evaluated in terms of their impact on quality-of-life-adjusted life-years (or QALYs). They are only approved if they produce enough QALYs per pound spent. The wellbeing approach is essentially an extension of this method.

There are of course important differences. Wellbeing is how people feel about their whole lives, not just their health. And we are looking at the effects of every aspect of policy, not just healthcare. Some of these effects are economic. So how does the wellbeing approach differ from traditional cost-benefit analysis, where benefits are measured in units of money? Traditional cost-benefit analysis can only be applied over a narrow range of issues where the benefits either have an actual price, or a value which is implicit in the choices people make. This condition is not satisfied in most of health, social care, child protection, law and order, the environment and redistribution. Indeed, the reason the state is active there is precisely because in these areas market valuations and outcomes would be sub-optimal. So in these areas there is really no alternative to wellbeing (directly measured) as the criterion of benefits.

However, traditional cost-benefit is a totally valid way of measuring benefits in those areas where it can be applied. So the two approaches are complementary and they can be combined by transforming the money measures of benefit (derived from traditional CBA) into wellbeing measures, by multiplying them by the marginal impact of money on wellbeing. The British Treasury’s Green Book manual of policy analysis now endorses ‘social wellbeing’ as the goal and approves the use of direct measures of wellbeing as well as their monetary equivalents.

Social justice

Is total wellbeing really the goal? Or should we not pay more attention to the prevention or the relief of misery? In other words, is it more important to raise the happiness of someone who is miserable than that of someone who is already happy? Jeremy Bentham opted for the total sum of wellbeing as the goal. But many modern thinkers would take a more egalitarian stance. They argue that it is more important to increase the happiness of those who are more miserable than to increase the happiness of those who are already happy.

There are two practical ways of implementing this more egalitarian approach. One is to measure social welfare not by total happiness, but in a way that gives less value to additional happiness the happier a person is. So when policies are being analysed, their value would be subject to sensitivity analysis to see how their comparative claims change as the analysis becomes more egalitarian.

Another, more practical approach, is to focus the search for new policies more heavily on those areas of life which account for the greatest amount of misery in society. This, in essence, is what the New Zealand government has done in its wellbeing budget from 2019 onwards.

The science of wellbeing

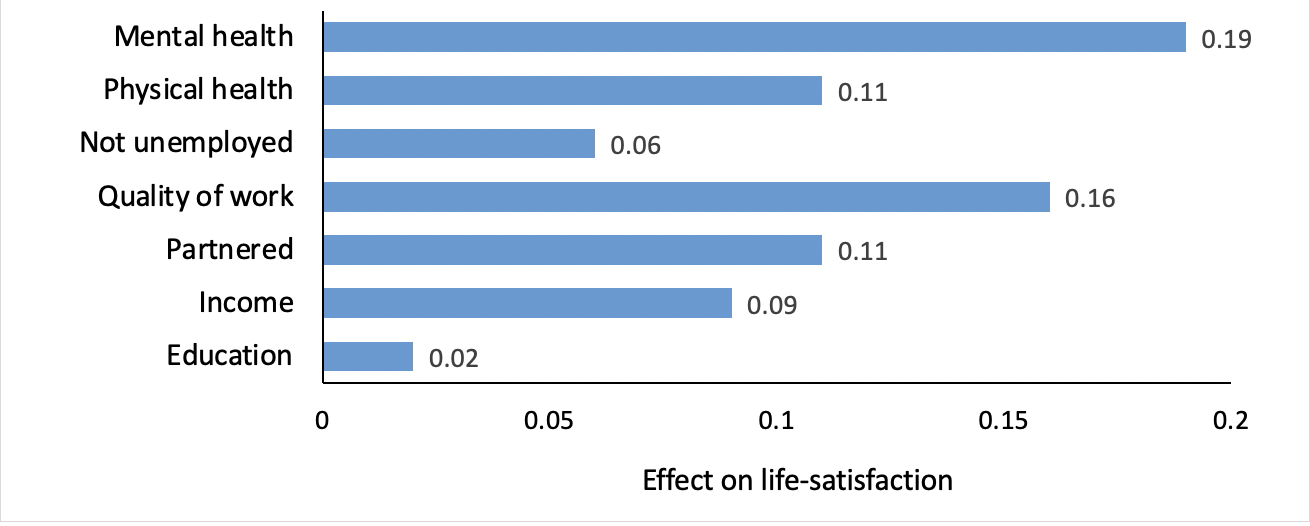

What are the main determinants of wellbeing? And what are the main causes of misery? Our team at LSE recently analysed the findings from major longitudinal surveys in Britain, Germany, Australia and the US. The findings were similar in all these countries, and Figure 2 gives the results for Britain. It shows how each factor contributes to the inequality of wellbeing, holding the other factors constant. A parallel analysis shows how much each factor contributes to the prevalence of misery, and the ranking of factors is the same for each analysis.

Figure 2. What matters for wellbeing?

Partial correlation coefficients

Source: Origins of happiness: evidence and policy implications. VoxEU.

Thus, as Figure 2 shows, more of the misery in our country is due to diagnosed mental illness than to any other factor – and physical illness is also important. Next come human relationships, at work and in the family, and only then comes income. So we need a new, broader concept of deprivation – the inability to enjoy life for whatever reason, rather than just because of poverty.

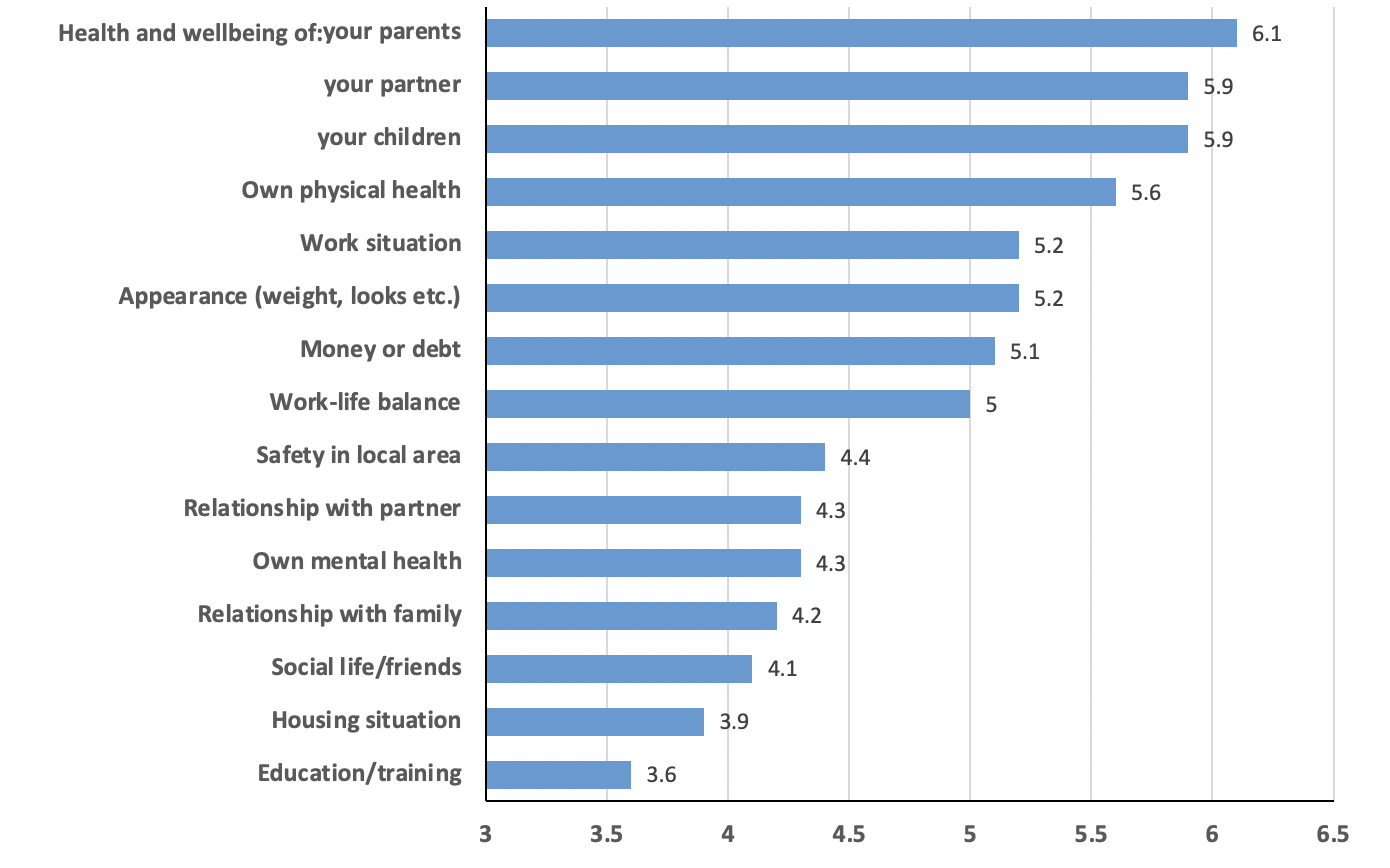

An alternative approach to priorities is to simply ask people “How much do you worry about the following issues (0 – never, 10 – a lot)?”. The results for a representative UK sample are shown in Figure 3. They broadly confirm the ranking of priorities shown in Figure 2.

Figure 3. “How much do you worry about the following issues (0 never, 10 a lot)?”

Source: Oxford Economics, What Do We Worry About Most? (2018). Survey by NatCen.

Many of our adult characteristics are laid down in childhood. Emotional health at 16 is a better predictor of a happy adult life than all the qualifications a person ever gets. But how can we influence a child’s emotional health? The evidence is striking: primary and secondary schools (and their teachers) affect the emotional health of children as much as their parents do.

The policy implication of all this is clear. Policy makers should give much lower priority to long-term economic growth and much higher priority to the services which sustain mental health, physical health, child development, family life and elderly care. It is the social infrastructure which matters most, not the physical infrastructure. To level up those areas which are left behind requires better services more than better economic infrastructure.

Experiments

In British schools there have been a series of attempts to teach life skills. The last Labour government introduced a programme called Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL). Its impact was evaluated in secondary schools and found to be zero – no effect on emotional, behavioural or academic outcomes. The reason was identified as insufficiently structured materials and a lack of teacher training. By contrast, a more recent four-year weekly curriculum in secondary schools called Healthy Minds was found to raise the student’s life satisfaction by 0.4 points (out of 10). If we convert this into a measure of quality-of-life, the cost per extra QALY was only £1,000 – well below the standard criterion of around £25,000 for additional health expenditure.

Turning to adults, hundreds of clinical trials of modern psychological therapy show 50% rates of recovery for depression or anxiety disorders after an average of some 10 sessions. They also show that the patients treated will work on average one additional month over the next two years as a result of the treatment. This generates enough additional income to cover the cost of the therapy. On this basis, Layard et al proposed a programme of Improved Access to Psychological Therapy. When implemented, the results of the trials were repeated in the field.

Cost-effectiveness and modelling

It is of course important to evaluate not only new policies but also existing policies in terms of their cost-effectiveness. This is not easy, and I offer Table 1 in the hope that others will improve on it. In it I examine the cost effectiveness of different ways of reducing by one the number of people in misery over a 12-month period. According to this analysis, the cheapest of the four methods is treating more people for depression and anxiety disorders (this analysis ignores the flow-back of savings). Active labour market policies come second – encouraging evidence of what we might expect from the current government’s Kickstart initiative. Then comes physical health, and finally come income transfers to the poor.

Table 1. Average cost of reducing the numbers in misery, by one person

| £k per year | |

|---|---|

| Poverty. Raising more people above the poverty line | 180 |

| Unemployment. Reducing unemployment by active labour market policy | 30 |

| Physical health. Raising more people from the worst 20% of illnesses | 100 |

| Mental health. Treating more people for depression and anxiety | 10 |

Source: Origins of happiness: evidence and policy implications. VoxEU.

This analysis is very crude. But, as time passes, it will become possible for finance ministers to do a much better job. For this they will need

much better experimental evidence; and

- a model of how an initial change in someone’s wellbeing affects their subsequent wellbeing and their subsequent claims on public expenditure.

The second is a major project, and will need significant money to finance it.

The length of life and WELLBYs

Many policies affect the length of life. So our measure of the impact of policies needs to take this into account. We want people to have lives which are long and full of wellbeing. So the simplest approach is to say that we want for each individual the maximum total wellbeing-years, where we simply add up the wellbeing in each year of their life. A natural acronym for wellbeing-years is WELLBYs (just as medics talk of QALYs measuring quality-of-life-adjusted life years). So we wish that each life will have the largest possible number of WELLBYs.

This approach has huge implications for policy. At present the value of life in terms of money is derived from one of two methods:

- People’s preferences, revealed by how much more they would need to be paid to do a job with a higher risk of death, or

- People’s stated preferences when asked what they would pay for a reduced risk of death.

These methods involve major assumptions. By contrast, the wellbeing approach is very simple: it simply examines the change in WELLBYs. And it implies a very different trade-off between money and life-years from that implied by traditional methods. In the wellbeing approach an extra year of life is of equivalent value up to £750,000. By contrast, existing methods yield values well below £100,000.

Which approach is the more plausible? Traditional values, for instance, would not justify a lockdown to save lives threatened by COVID-19, while the wellbeing approach would. And public opinion supported the lockdowns. So the wellbeing approach would seem to be in tune with public opinion. Thus it does seem that future policies should give more weight to the preservation of life relative to other objectives – compared with what happened before COVID. This does not mean an increase in public expenditure, which we take as given. But it does mean a rebalancing.

The effect of wellbeing on other goods

We have so far focused single-mindedly on wellbeing as the overarching good. But, even if you do not buy that, you should take wellbeing very seriously because of its good effects on other things you value.

Making children happier makes them learn better.

Your wellbeing predicts your subsequent longevity better than a medical diagnosis does.

- Greater wellbeing increases productivity.

- Happy people create more stable families, and happy people are more pro-social.

Conclusion

The wellbeing approach is not new: its adherents have included William Beveridge and Sidney and Beatrice Webb, the founders of the LSE. But now its time has come. More and more universities around the world are teaching the subject, producing a body of trained analysts able to apply these ideas to policy. The OECD have persuaded member countries to measure the wellbeing of their people. The governments of five countries have formed an alliance called the Wellbeing Economy Governments partnership (WEGo). So we shall surely see a major change in policy making – with the common currency not money, but wellbeing.

This post is an edited extract from Layard, R., 2021. Wellbeing as the Goal of Policy. LSE Public Policy Review, 2(2), p.1. It represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

Could I translate this brief

Could you email me at r.taylor6@lse.ac.uk? Thanks