Kiera Glendenning reflects on her experience researching the records of the Lock Asylum – an 18th century charity for the rehabilitation of ‘fallen’ women. She discusses the themes that emerged from her research as an undergraduate researcher and then as a research intern, her attempts to understand the women she encountered, and how they have changed the way she thinks about history.

Jane Floyd entered the Lock Asylum on Thursday 25th October 1787, after ten years working as a prostitute in London. The one-page biography recording her admittance shows she was 20 years old at the time. She began her career at age 10. Prostitution was only the start of her troubles. The case report goes on to describe how she had “been four times salivated [received mercury treatment] for the venereal disease [syphilis].” Whilst mercury was intended to stimulate the flow of phlegm and carry away the venereal poison, for many it worsened their sickness or even killed them.

Jane’s story of underage prostitution and recurrent syphilis is typical of the women I encountered in the Asylum records. These stories reveal the precarity of life for working- and middle-class women in 18th century London, where the only alternative jobs available to them were hard to come by, poorly paid, and often held their own dangers. The project has also brought me closer – emotionally – to the women I studied than I thought possible even as it raised more questions than it answered about their experiences inside and outside its doors.

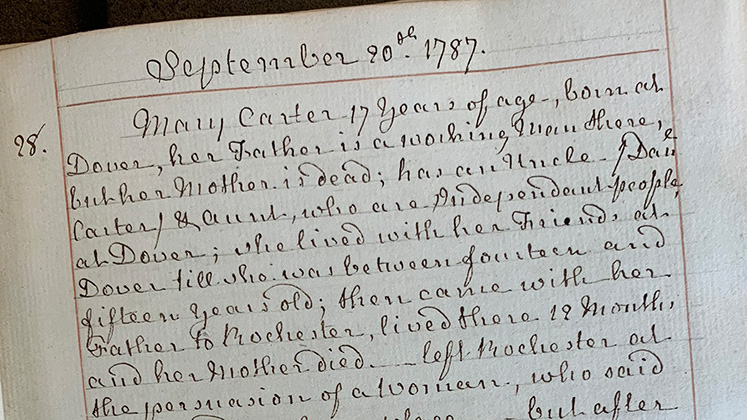

The Asylum was established in 1787 as a charitable institution, focusing on the ‘rehabilitation’ of ‘fallen women’ and not their medical treatment. Jane Floyd was one of hundreds of women whose lives were documented at admission in the handwritten register during the 1780s and 90s. Women were only accepted into the Asylum with a letter of recommendation, and with a demeanour the board, made up of evangelical reformers, considered repenting enough for salvation.

The women were almost exclusively syphilitic sex workers who were forced to enter the Asylum after their profession had left them with a venereal disease they could no longer hide from their customers. The admission register offers a unique opportunity to study their lives directly rather than through the recollections of the men who used them. However, often only running to a couple of sentences, the biographies can only reveal glimpses of each woman’s story.

Reading though the accounts, I was struck by the levels of abuse and misfortune these women suffered. References to child abuse abound, as well as the death of parents and husbands. In the later 18th century, there were few employment opportunities for independent women. Male protection, from a father or husband, was a necessity for many women’s economic wellbeing. Losing this, through abandonment, death, or unbearable abuse, forced many women to turn to prostitution or face starvation.

Whilst the admittance records of the Asylum were invaluable sources, my attempts to understand the experience of the women also went beyond the documentary record. I attended a theatre workshop with Cara Jennings and Sophie Trott, where we improvised scenes, using the register cases as prompts. We sat together, taking on the role of women from the register, sewing pockets like they did in the Asylum, and engaging in improvised conversation. We were forced to weave an imagined narrative through the vast gaps in the source material. We could not help considering their experiences, how modern women would react, and how we would have coped in such situations. I was amazed by how forcefully I connected with the individuals I was researching.

As well as bringing personal connection, studying the Lock Asylum has also changed the way I think about history. Whilst our history is expansive, it is also made up of billions of individuals, who all faced their own challenges and successes. The great men of history, be it Nelson or Napoleon, have many acolytes willing and able to tell their story, but it is far harder to hear from the women who, whilst individually made no great mark on history, have given the world its current shape and colour.

Jane Floyd was one of them, flashing in and out of my historical vision. Her story has left me with a particularly long list of unanswerable questions. I wonder at the state of her family home. We know her mother was dead, but what of her father? A lamp lighter and milk carrier by trade, William Floyd was a working-class Londoner. He was also religious, having had Jane baptised, despite the personal costs, in the parish of St Giles in the Fields in May 1767. The religious vigour of her father contrasts sharply with Jane’s move into sex work at 10. Perhaps her father died; perhaps he was cruel. Her case reveals only that, “she left him about ten years agoe & went upon the Town.”

We know little else about Jane’s life. Her record states she ran away to parts unknown a few days before Christmas 1787, having stayed in the Asylum for less than two months. As with so many who passed through its doors, my encounter with Jane Floyd was fleeting yet powerful, enlightening, and enigmatic. And for me, at least, it was a privilege.