Visiting academic Richard Franke shares findings from his research into the causes of regional variations in mortality during the 1918 “Spanish Flu” pandemic. Two of the most important drivers of COVID-19 mortality are poverty and pollution (Beach et al., 2020). Do these factors explain regional differences in death rates at the beginning of the 20th century as well?

I show inequalities in income and air quality are associated with considerable differences in mortality in the German kingdom of Württemberg in 1918. These findings reveal important parallels in the relationship between epidemics and inequality that have persisted for a century at least. These inequalities urgently need addressing.

The 1918 “Spanish Flu” was the deadliest pandemic in modern history. Between 50 and 100 million people died (Johnson and Mueller, 2002). Like COVID-19, the Spanish Flu came in waves. The first of the 1918 influenza pandemic reached the South-West German Kingdom at the end of World War I in June 1918. A second, more deadly wave followed in October 1918 and finally the third wave in spring 1919.

The average all-cause mortality rate in Württemberg was 15.8 deaths per 1,000 persons during the pandemic year 1918, corresponding to a mortality rate increase of 2.9 deaths or 23 percent relative to the baseline in 1917.

The public perceived the pandemic as a minor problem despite influenza deaths increasing by about 3,000 percent in 1918 compared to previous years. The pandemic hit a starving, war-ravaged population and already about 14 percent of military-age males were missing. War, and censored media, explain why the effects of Spanish Flu did not cause greater public concern.

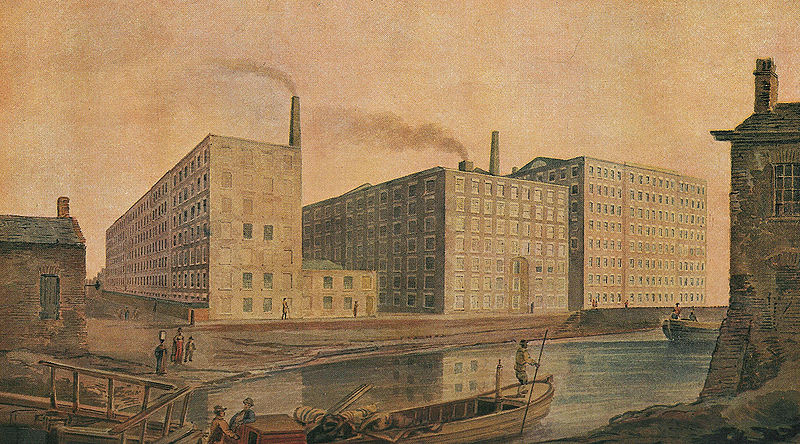

I compare mortality rate changes in poor (least polluted) parishes to rich (highly polluted) parishes. Figure 1 illustrates the annual mortality rate per 1,000 persons for parishes in Württemberg by pollution tercile. Pollution is measured as installed coal-fired power plant capacity within 50 kilometers of the respective parish. Figure 2 shows the annual mortality rate by income tercile. The figures show that mortality rates evolved largely in parallel outside of the epidemic. In 1918, however, the trends diverged.

Middle and high-income parishes (classified by taxable income per capita) recorded a significantly lower increase in mortality rates than low-income parishes. The respective increase in the mortality rate in medium and high-income parishes was lower by 1.3 and 0.9 deaths per 1,000 population.

Moreover, the mortality rate increase from 1917 to 1918 was significantly higher in highly polluted parishes compared to least polluted parishes. The estimates indicate an additional increase in the mortality rate by 1.6 deaths per 1,000 population.

To illustrate, the model predicts about 39,000 deaths in 1918. The estimators suggest that this number of deaths could have been reduced by 400 deaths if all communities had been in the highest income tercile, and by another 1,600 deaths if all communities had been in the lowest pollution tercile.

The spike in 1918 mortality was particularly large in poor and highly polluted parishes. The results are robust even after I account for alternative explanations such as wind patterns and changes in model specifications or sample composition.

The findings add to the mounting evidence of the detrimental effects of regional income inequality and exposure to air pollution and call for action to address these inequalities.

References

Beach, B., Clay, K., and Saavedra, M. H. (forthcoming) The 1918 influenza pandemic and its lessons for COVID-19. Journal of Economic Literature.