In this piece recent Economic History MSc graduate Nicholas Accattatis investigates the most famous critical juncture in the history of institutional development: England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688. Accattatis uses the framework of ‘choice architecture’ from behavioural economics to analyse the Convention Parliament of 1689, the Parliament which enshrined the achievements of the Glorious Revolution into the English constitution. Some edges of the MPs’ choice architecture were kept sharp by stoking spectres of violence, while others were kept soft by deft politicking.

Institutions develop slowly and then all at once during short episodes of drastic change. Economic historians call these episodes of drastic change ‘critical junctures’.

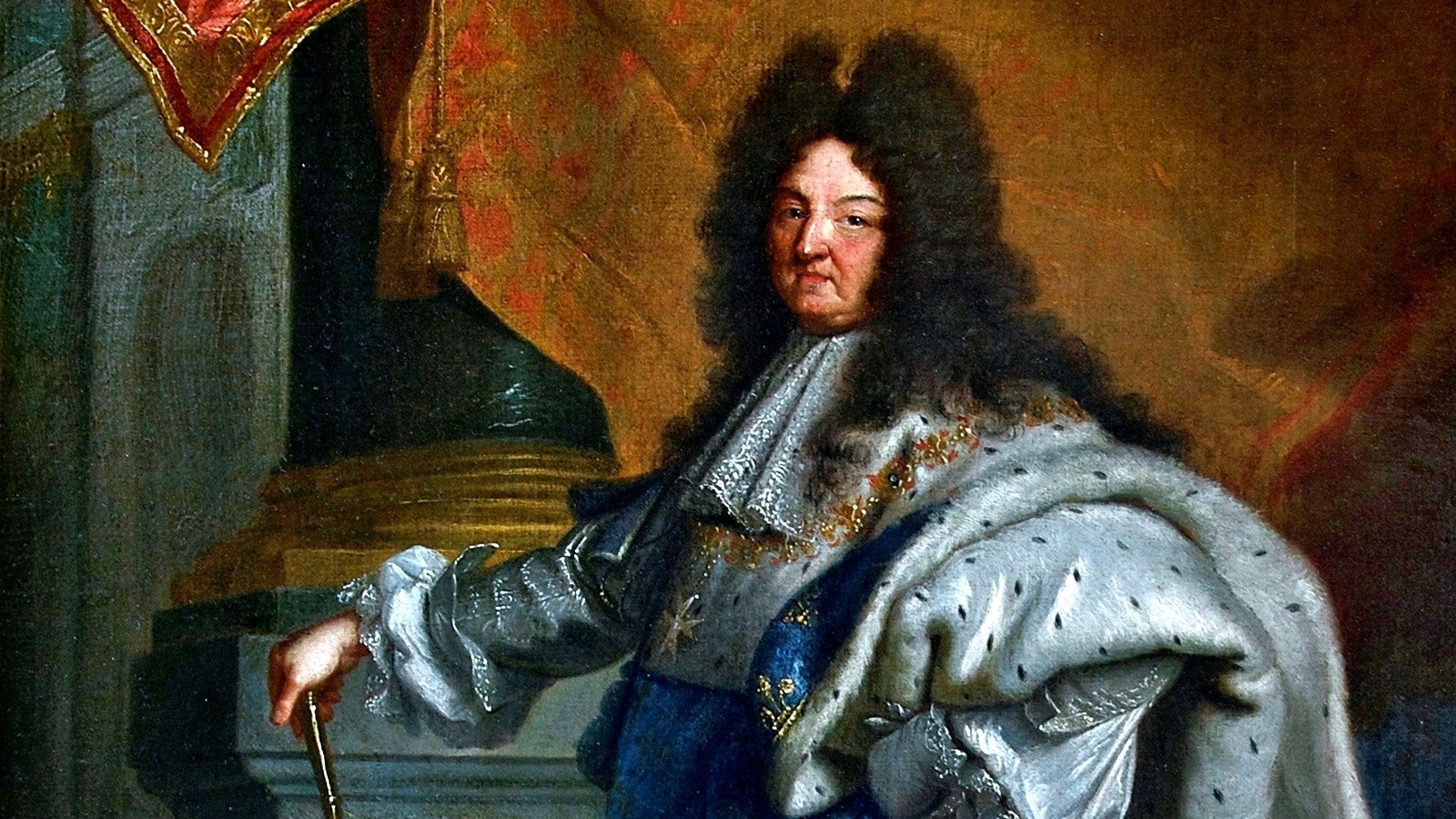

The most famous critical juncture in the history of institutional development is England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688. After the Glorious Revolution the arbitrary power of the monarch was limited and the private property rights of the English were improved. Yet explaining why a critical juncture is important does not explain why it happened the way it did. The Convention Parliament of 1689 cemented the achievements of the Glorious Revolution into the English constitution. How? The MPs who led the charge deftly managed the emotions of their fellow members.

Institutional economic historians often use ‘rational choice theory’ to account for institutional change. Rational choice theory assumes that individuals make decisions based on calculations of rational self-interest. But to understand why the Convention Parliament voted to confirm William as king, rational choice theory can take us only so far. In the heat of revolution the MPs were less likely to act by cool rationality. Indeed, afterward a critical mass of MPs and Peers blamed the “fervour of revolutionary impulse,” for their decision to vote for William.

Instead of rationality, behavioural economics stresses the importance of actors’ ‘choice architecture’. Choice architecture refers to how choices are presented, and how those presentations can affect decision-making. The number of alternatives, the manner in which these alternatives are presented, and if there is a default choice available, affect the choice architecture of the decision-maker. Choices with only a few options, requiring urgency, presented in emotional contexts such as fear or anger, alter the quality of a decision-maker’s risk assessments and changes their risk preferences. In behavioural-economist speak, these emotions change the choice architecture upon which the decision-maker decides.

In the Convention Parliament of 1689, three emotions influenced the MPs: fear, anger, and enthusiasm. These emotions made the MPs prefer swift rather than delayed action. But a quick solution was only possible if these emotions could be managed properly. In the end the Williamites – the pro-William faction – were able to harness these emotions of the MPs to obtain a majority.

The Williamites aroused the fears of the MPs with spectres of violence. The English feared a Catholic takeover of Ireland, leaving Protestant England exposed to confessional rivals who had reason to hate them. In fiery speeches the Williamites conjured fears of a “massacre of 200,000 Protestants in Ireland that would replicate itself in England.” England was also vulnerable to invasion by the French, the foremost rival of the soon-to-be King William III.

In only a week the Williamites convinced key members in the Convention to crown William. Lord Danby was persuaded by his fear of the deteriorating situation in Ireland to switch allegiances. The Earl of Thanet relented because he had been convinced of the “necessity of having a Government.” Another Lord changed their mind after “the apprehension of Popery made [him] imagine [his] children frying in Smithfield.” The urgency aroused by the Williamites also made it harder for the Jacobites – the faction supporting the deposed James II –to regroup and question thoroughly William’s motives and the legality of crowning him.

The Williamites also had to soothe the anxieties of undecided MPs. The Convention Parliament needed consensus, not alienation or indignation. If still-undecided MPs dug in against the Williamites, partisan debate could have stalled the Parliament, and the Williamites would have been distracted from getting William on the throne. Both anger and enthusiasm were to be suppressed while the fear of invasion kept the pressure.

The Williamites kept the Parliament insulated from the partisan crowds gathering in London outside the House of Commons. During a pivotal debate a letter and a petition from opposing sides were delivered to Parliament’s doorstep. The letter was from James. The petition was delivered by an angry mob, signed by Londoners who wanted Parliament to crown William. The Speaker of the House, a Williamite, wisely disregarded both documents for fear they would rally undecided MPs to take a partisan side.

The Williamites knew what they were doing. Many in the Williamite camp were experienced statesmen who had tried to exclude James from the throne in 1685. They had learned from their past failure not to be distracted by discussion on grievances and rights. Their focus on enthroning William meant that they were willing to cede the discussion on rights and grievances to a Whig-heavy special committee. Less than two weeks later, at their coronation William and Mary signed the Declaration of Rights, the most significant institutional legacy of the Glorious Revolution.

The Williamites kept some edges of the MPs’ choice architecture sharp with spectres of violence and kept other edges soft with deft politicking. They succeeded, to the chagrin of many. Economists, historians, and political scientists would do well to remember that critical decisions are ultimately made by people, often fearful, angry, and enthusiastic. And with people, anything can happen.