The theme of the 2016 LGBT History Month is ‘religion, belief and philosophy’. In the wake of the January 2016 meeting of the leaders of the worldwide Anglican Communion, the Revd Dr James Walters – chaplain and senior lecturer in practice at LSE – highlights the legal work and perspective of William Stringfellow, an LSE alumnus who ‘took great risks with his own reputation … to defend gay people and to enable others to reconcile their identity with their Christian faith’.

The meeting in January of the leaders of the worldwide Anglican Communion in Canterbury was another difficult reminder that LGBT rights are not a cause to which the whole world has signed up. While equality is increasingly recognised in North and South America, Europe and China, many other countries are moving depressingly in the opposite direction. Those include some parts of the Commonwealth where Anglican Christianity is now most populous and fervent.

So while the final communiqué of the meeting included a renewed opposition to the criminalisation of homosexuality and was accompanied by an unprecedented apology from the Archbishop of Canterbury to lesbian and gay people for ‘the hurt and pain, in the past and present, that the church has caused’, the practical outcome deemed necessary to hold these diverse national churches together was a sanctioning of the American Episcopalians for their acceptance of same-sex marriage.

The Episcopal Church has long been progressive on this and many other issues. But that does not always arise, as its opponents claim, from the knee-jerk liberalism of a decadent society. One LSE alumnus of the 1940s, who was a prominent member of the American Episcopalian Church, showed how affirming lesbian and gay people was one implication of taking the message of Jesus Christ seriously. And he was saying this at a time when both American and British societies at large were a long way from agreeing.

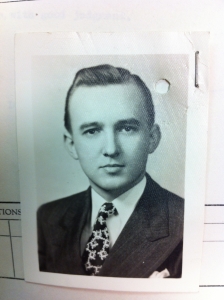

William Stringfellow arrived at the LSE in 1949 as a politically ambitious young man on a Rotary scholarship. But while in London he seems to have experienced a radical deepening of his Christian faith in a way that drew him towards a more sacrificial life, committed to the service of those on the margins of society. He later wrote, ‘I had elected [while at the LSE] to pursue no career. To put it theologically, I died to the idea of career and to the whole typical array of mundane calculations, grandiose goals, and appropriate schemes to reach them.’[1] On returning to America he studied law and established a legal practice in East Harlem where his clients were immigrants, the poor and the socially excluded.

It seems likely that Stringfellow’s reappraisal of life goals in London was linked to an emerging awareness of his homosexuality. His letters express feelings of same-sex attraction as early as 1947[2] and his biographer Anthony Dancer has suggested that Stringfellow’s move into the legal profession was in part a desire to understand the law as an instrument of oppression of gay people. At this time, homosexuality invoked shame and stigma in both church and society and was punishable by lengthy prison sentences or hard labour. By the early 1960s Stringfellow was actively involved in legal counsel for gay people and in 1965 he addressed a group of gay Christians in Christ Church Cathedral, Hartford, Connecticut, giving legal advice in the event of arrest and offering, what was then, a bold defence of homosexuality from a Christian perspective.[3]

He begins by asking, ‘Can a homosexual be a Christian?’, a question he dismisses as absurd. ‘To be a Christian does not have anything essentially to do with conduct or station or repute… To be a Christian has, rather, to do with that peculiar state of being bestowed upon men [sic] by God… It has to do with that form of self-acceptance which is a gift of God and not something achieved or sustained.’ This is one expression of Stringfellow’s resolute conviction that to associate Christianity closely with any moral stance is to reduce the Gospel to some ideology. ‘I am a Christian, not a moralist, so I am not too much impressed by the mere fact that homosexuals are rejected by society.’ He points out that Jesus himself spent his ministry with ‘whores and tax collectors, the blind and the idiotic, lepers and insurrectionists, the poor and those possessed by demons.’

But this could merely be a version of the ‘love the sinner, hate the sin’ argument which continues to leave LGBT people in a second-class category. So he goes on to ask the more important question, ‘can a Christian be a homosexual?’ His conclusion is that sex, whether heterosexual or homosexual, can fall into different moral categories. It can be manipulative or abusive, and he is clear that ‘homosexuals hold no copyright on parasitic sex.’ It can be playful or pleasurable, something for which he found ‘no condemnation in the Gospel’. And finally, it is possible for sex to become the sacramental expression of God’s love for humanity. ‘All of life is sacramental, that is, the outward sign and symbol of a person’s reconciliation within himself and with all others. For Christians, sex, whether homosexual or heterosexual, can be one, among many, sacraments of that reconciliation.’

Stringfellow himself never fully ‘came out’ in the sense we would define it today. Yet he took great risks with his own reputation in the legal work he did to defend gay people and to enable others to reconcile their identity with their Christian faith. The closest he came was in defying his publisher’s instruction that he remove the reference in a 1982 book to his partner Anthony Towne as his ‘sweet companion for seventeen years’. No doubt some Anglican leaders would continue to be disgusted by such a description today. But were they to engage with Stringfellow’s writings they would not find an unbiblical liberal contorting the Gospel to suit his ‘lifestyle choices’, but a Christian of great integrity and thoughtfulness who drew all kinds of radical conclusions from the teaching of Jesus. So we can hope that as Christians around the world go deeper into their scriptures and traditions, they too will find greater legitimacy for the support of LBGT rights.

* The Revd Dr James Walters is chaplain and senior lecturer in practice at LSE. He has recently published ‘The Defiant Ringmaster: Lessons in Christian Leadership from William Stringfellow’ in the Anglican Theological Review, fall 2015.

Notes

[1] From ‘Simplicity of Faith’ in A Keeper of the Word: Selected Writings of William Stringfellow, ed. Bill Wylie Kellermann (Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1994), p. 30

[2] Anthony Dancer, An Alien in a Strange Land (Eugene, Oregan: Cascade, 2011), p. 194.

[3] Extracts taken from The Humanity of Sex (1965) in the Stringfellow Archive at Cornell University.