By Ivana Popovic

Is EU conditionality most effective at times of heightened “demand” by a would-be member state?

Yes, many would say. The argument goes that prospective member states are more vulnerable to give in to Brussels’ pressure in the run-up to events that constitute landmarks in the accession process: Stabilization and Association Agreement, candidate status award, opening of the candidate-EU negotiations, and the likes. The logic is simple: a needy state is malleable by the EU “stick and carrot” approach, hence we can expect the former not only to meet the formal accession criteria (e.g. Copenhagen), but also to bow to extra “side conditions” pertaining to non-accession matters.

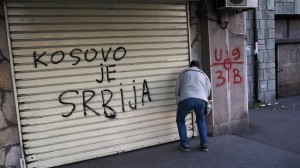

The recent accord between the Serbian government and Kosovo authorities has been raised by pundits as a case in point. Two months ago Serbia agreed to cross what has been marked the “red-line” by the previous government – it held nine rounds of talks with Kosovo representatives, resulting in an agreement which regulates the position and status of the Serbian-majority populated municipalities in the north of Kosovo, including border, police, and judic iary issues. This all coincides with the expectation of the EU approving the beginning of negotiations about the Serbian membership, due to be decided upon on 28 June. Hence the conclusion that Serbia agreed to go “farther” in its talks with Kosovo owing to the expectation of obtaining EU accession negotiations, whereby the EU pushes Serbia to undertake steps which would contribute to Kosovo’s independence, if not in one step – than in a piecemeal way.

iary issues. This all coincides with the expectation of the EU approving the beginning of negotiations about the Serbian membership, due to be decided upon on 28 June. Hence the conclusion that Serbia agreed to go “farther” in its talks with Kosovo owing to the expectation of obtaining EU accession negotiations, whereby the EU pushes Serbia to undertake steps which would contribute to Kosovo’s independence, if not in one step – than in a piecemeal way.

But such conclusions might be misleading. While Serbia has no doubt been subjected to increasing pressure since the new government formed in the summer 2012, the sources of this pressure, as well as the Serbian officials’ readiness to be “cooperative” during the Kosovo negotiations, are more varied and dispersed than the EU conditionality narrative holds. Although the reports and analyses of why Serbia crossed its “red line” mention the EU as the core driver of the recent “breakthroughs”, the mechanisms of rendering such pressure effective lie beyond Brussels and have much to do with the political elite’s “face lifting” and the growing crisis.

Take the so called “re-branding” of once nationalist elites. The current government is run by hard-liners from the Milosevic’s time, and since the “5th October Revolution” (2000), which spelled the end to his regime, this is the first coalition dominated by former nationalist parties, notorious for their political (mis)deeds in the 1990s. Now the ruling Serbian Progressive Party, as well as the Socialists Party (once Milosevic’s), are making an effort to portray themselves as moderately conservative, pro-European parties, who have discarded the radical anti-European discourse. As a result, the government is resolved to stay away from international disagreements, let alone open conflicts, be they related to regional or wider foreign affairs. Therefore any failure to move the Kosovo talks forward by making concessions to the opposite side would be met by concerted charges that the once nationalists in fact have not altered their manner of confronting with the West.

Another cause of Serbia’s craving to maintain good relations with the West (that is – EU plus US) is its economic woes. The dire state and ongoing crisis, with a historically highest public debt of almost 60% of the GDP, non-existent growth hovering around 0%, inflation amounting to 14%, and gloomy demographic prospects, Serbia has entered a vicious circle of dependency on foreign loans, in the first place IMF arrangements, as the only means of “plugging the holes” in the ailing economy. To keep the door open to prominent lenders, Serbia must not oppose major Western forces that sway and have a say in the international financial institutions. Therefore financial concerns play a significant role in preventing Serbia from being a tough negotiator in matters of interest of major Western powers, and since the countries like the USA, Germany, UK, and France have all been persistently pushing for Kosovo independence, a fully-fledged resistance by Serbia would be treated as an act of hostility that warrants some form of retaliation through the proverbial “stick and carrot” manoeuvre.

To conclude, although the recent concessions by Serbia are mainly attributed to its EU aspirations and the upcoming Brussels’ decision, the sources of external pressure as well as the drivers of domestic officials’ retreatist attitude are distinct from the mere EU accession concerns. For the first time since 2000 major Serbian parties agree on the necessity to move towards EU membership in foreign policy. However, due to a EU-accession fatigue and citizens’ resentment, with the support for EU integration being on a record low since 2000 – only 45% of the population endorsing it, any further progress towards EU membership is low likely to reward the ruling parties with bigger electoral support and it seems an overstatement to say that the government is playing the EU card for domestic political purposes. It is rather the power of EU leading states, as well as non-EU actors such as the USA, of shaping the image of once nationalist elites interested in re-branding and legitimizing as credible interlocutors, plus the “purse power” within international financial institutions that make Serbia more yielding when negotiating issues not strictly related to the Copenhagen-criteria. Hence the fact that a country is increasingly malleable when an important EU decision is being awaited doesn’t necessarily mean that EU conditionality is more effective during such periods. This malleability can be driven or reinforced by other actors or processes. Despite overlapping and intertwining with some EU actors and institutions, such mechanisms of influence are more complex and stretch beyond the Brussels’ “sticks and carrots”.

Ivana Popovic is a master’s student of international relations and security at the

University of Westminster, London.

Eu support may only be 45% but Pro eu western parties are the only parties that win!! The nationalist parties are dead! Radicals and dss are over! Serbia wants pro eu governments that support the independence of Kosovo for eu membership! Kosovo is independent to 63% of Serbs.

Pingback: EU Conditionality or Crisis-Induced Compromises: Why Serbia agreed to be Cooperative in Kosovo Negotiations | International Affairs at LSE