Using data from the Italian Chamber of Deputies from 1979 onwards, Licia Claudia Papavero and Francesco Zucchini find that women form a more cohesive group in parliament than men do, and that parties with greater numbers of women are more cohesive. In light of these findings, Italian party leaders would do well to select more women candidates.

Using data from the Italian Chamber of Deputies from 1979 onwards, Licia Claudia Papavero and Francesco Zucchini find that women form a more cohesive group in parliament than men do, and that parties with greater numbers of women are more cohesive. In light of these findings, Italian party leaders would do well to select more women candidates.

Some studies on female legislative behavior have suggested that women parliamentarians may challenge party cohesion by allying among themselves and across party lines, especially when women-related legislation is at stake. Using the Italian parliament as a case-study we found that women both form a sub-group that is more cohesive than men in their parties, and that being a woman positively affects party cohesion.

How can we measure ‘gender cohesion’ and ‘party cohesion’?

In contemporary political science, the concept of party cohesion has an immediate spatial description. Individual preferences on the policy space are represented as individual ideal (or policy optimum) points. The proximity of each MP to a specific subset of other MPs (such as other men or women) can be measured by the distance separating each MP’s ideal point from the median position of this subset. We call this measure dispersion. When the average ‘party dispersion’ of MPs belonging to a given party is high, then the cohesion of that party is low. Similarly, when the average ‘gender dispersion’ of women (or men) MPs in a party is high, the ‘gender cohesion’ in that party is low.

It is not easy to empirically estimate the policy preferences of MPs’, because such preferences cannot be directly observed, only inferred from MPs’ behavior. In light of this, we considered co-sponsoring of legislative bills as a way of determining preferences. Our main reason for using bill co-sponsorship to determine the preferences of MPs is that this data source is source much less affected by party and Cabinet discipline (at least in the Italian political system).

We used data provided by the Italian Parliament website about all the bills introduced in the Italian Chamber of Deputies between 1979 and 2008. Employing a statistical technique we extracted the ideal-point estimates of all the MPs (their optimal preference points). The underlying idea is that the more any two MPs co-sponsor the same bills then the closer are their ideal points.

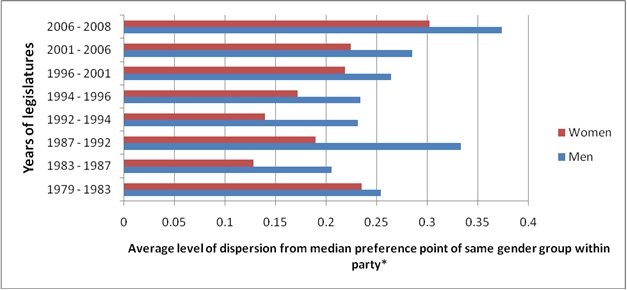

Gender dispersion within parliamentary parties

We first measured gender dispersion within parliamentary parties, which is the average level of difference in the preference of individual male or female MPs from the preferences of of other MPs of the same gender group within their party, by calculating the median level of preferences of the group of women and the median level of preferences of the group of men in each party. We then calculated the distance of each MP from the median of preferences in his or her gender group in his or her party. From, this we were able to calculate the means (averages) of these distances separately for women and men. So, a lower average level of dispersion for women would mean that women tend to co-sponsor parliamentary bills with other women of the same party more than men do co-sponsoring with other men of the same party. Figure 1 below compares these averages for men and women in each legislature since 1979. According to our analysis, with lower levels of dispersion within each single party, women form a much more cohesive group than do men in all the Italian legislatures considered – a pattern that persists for three decades.

Figure 1: ‘Gender dispersion’ on co-sponsoring bills within Italy’s parliamentary parties, from 1979 to 2008

*Note: A lower average level of ‘gender dispersion’ means that women tend to co-sponsor parliamentary bills with other women of the same party more than men do with other men of the same party.

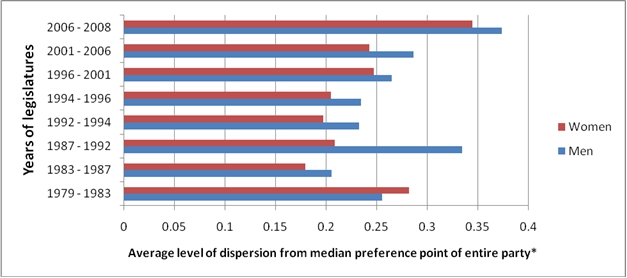

Party dispersion by gender

We used a similar measure to calculate party dispersion by gender, which is the average level of difference in the preference of individual male or female MPs from the legislative preferences of the majority in their party (men and women included). After calculating the median (ideal) preference point for each party as a whole, we then calculated the distance of women MPs and the distance of men MPs from this median separately for each party. We used this data to calculate the means (averages) of these distances separately for women and men, and then compared them for each legislature, as shown in Figure 2 below.

In looking at ‘party dispersion’ across gender groups, a lower level of dispersion for women means that they are more “cohesive”(or if you prefer it, they are more loyal towards their party) because they tend to co-sponsor bills with other MPs of the same party more than men in their party do. In all Italian legislatures, except the period 1979 to 1983 (the 8th), women are less dispersed from the median of their parties than men are, that is, they are closer to the legislative preferences of the majority of their parties, a pattern that endured for 25 years.

Figure 2 – ‘Party dispersion’ on co-sponsoring bills by gender, for Italian parliaments from 1979 to 2008

*Note: A lower level of ‘party dispersion’ for women means that they are more “cohesive”(or more loyal towards their party) because they tend to co-sponsor bills with other MPs of the same party more than men do.

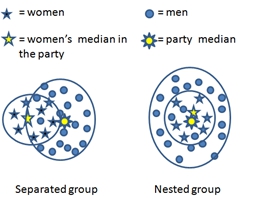

Because women are a minority within each Italian parliamentary party, we can define them as a “nested group” instead of a “separated group”, illustrated in Figure 3 below. Far from being an element of heterogeneity, women seem on average to strengthen party cohesion.

Figure 3 – Women as separated and nested group

A spurious effect?

The evidence we have considered so far may depend on many other factors, and this multi-causality means that the apparent connection between gender and cohesion might in fact be a spurious one. Thus, we can properly assess the impact of gender and its meaning only by a multivariate analysis at the individual level, one that explicitly considers such factors. Among them we should control first and foremost for whether women MPs are concentrated in certain parliamentary parties, which differ from the others. Relevant aspects here are the ideology of parties with more women (left-right), their pattern of organization (Communist vs. non Communist parties) and their size; the professional background, age, parliamentary seniority, and party experience of MPs; and the electoral system in use when the MPs were elected. Once this rich variety of variables is controlled, we find that being a woman continues to have a negative effect on how far MPs are from their parties’ medians. So the effects charted above are clearly not spurious ones.

Gender effect or minority effect?

In the Italian Lower Chamber the number of women has never risen higher than 23 per cent, and within the big parliamentary parties has never been above 30 per cent. Such a circumstance might suggest that the apparent effect of gender on party cohesion is in fact a byproduct of the frequency with which women are elected in the parliamentary parties. The possibility here would be that the gender effect does not depend on some substantial and enduring difference in women’s policy preferences compared to men.

We can consider two different theories here: cooptation theory and critical mass theory. According to the former, both men and women are selected according to a lexicographic criterion: first aspirant politicians close to the central preferences of the party are chosen, and then aspirant politicians succeed who are more and more distant from the party center. When the sample of women recruited is smaller than the sample of men, the percentage of women close to the party center will be much higher than the percentage of men in the same condition. As the representation of women grows in comparison with that of men, then the impact of gender on party cohesion would have to diminish. Alternatively, the so-called critical mass theory predicts that when a minority group grows in size and overcomes a certain threshold, its members can more effectively overcome the pressure to emulate the majority group’s preferences.

Both theories suggest that an increase in the number of women over time would imply a decrease in both their gender and party cohesiveness. Yet, our data rejects this prediction. So, controlling for everything else relevant, we can say that in the Italian parliament being a woman persistently and positively affects party cohesion. If party cohesion reinforces a party’s brand, then selecting more women as candidates could be a good investment for the party leadership.

This finding opens the door to further research about why the increase in the number of women elected does not increase their variety (their dispersion), as is the case with men. It is very likely that beneath this gender difference in party cohesion there are patterns of legislative recruitment that are very different for women and men. On the one hand, if women MPs formed a group well integrated in the party establishment, with also some influence on the process of selection and recruitment of other women, they probably could co-opt female prospective MPs with very similar preferences, and achieve some shared policy goals once in parliament.

On the other hand, the persistent proximity of women MPs to the centre of the party (to the leadership) may be also interpreted as the effect of a persistent political weakness of women. Being a woman in parliament could be like being a rookie, a condition of relative and primary deprivation that cannot be broken up by other elements. In this case, women selected and recruited by the party leadership would count mainly (if not only) on the political resources that the leaders can guarantee them. They would be more dependent on leadership backing for their political careers than was true of men in the same party. If correct, the greater party cohesion for women would here mean a relative lack of autonomy from the party leadership for women MPs

A longer version of this paper is available here.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/OaO2LY

_________________________________________

Licia Claudia Papavero – University of Milan

Licia Claudia Papavero – University of Milan

Licia Claudia Papavero is a Research Fellow and Adjunct Professor in Political Science at the Department of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Milan. Her research interests focus on comparative legislative recruitment, legislative behavior and political representation from a gender perspective.

–

Francesco Zucchini – University of Milan

Francesco Zucchini – University of Milan

Francesco Zucchini is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the Department of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Milan. He has been a visiting scholar at Harvard University and the University of California. His research interests are chiefly focused on Legislative Studies, Courts and Rational Choice, Institutionalism. He has also published papers on Italian parliamentary elites and Italian immigration policies.

1 Comments