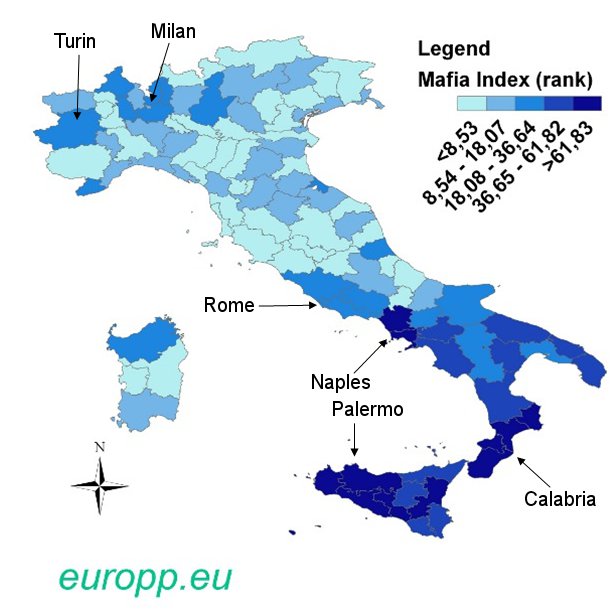

From the Godfather to Tony Soprano, the idea of the Mafia continues to have a special place in Western popular culture. Francesco Calderoni argues that despite the popularity of Mafia stereotypes, relatively little research has been carried out on the actual link between organised crime and politics in Italy. By mapping the areas of the country which have the highest Mafia presence, he illustrates the extent to which the problem has spread beyond the traditional hotspots of Mafia activity in Naples, Western Sicily, Northern Campania and Southern Calabria.

From the Godfather to Tony Soprano, the idea of the Mafia continues to have a special place in Western popular culture. Francesco Calderoni argues that despite the popularity of Mafia stereotypes, relatively little research has been carried out on the actual link between organised crime and politics in Italy. By mapping the areas of the country which have the highest Mafia presence, he illustrates the extent to which the problem has spread beyond the traditional hotspots of Mafia activity in Naples, Western Sicily, Northern Campania and Southern Calabria.

At the international level, the perception of the general public about the Italian Mafias is mostly based on stereotypes and clichés. Decades of mafia movies (e.g. the Godfather), TV series (e.g. the Sopranos) and media reports (e.g. the famous Der Spiegel cover with a gun on a spaghetti dish), have contributed to a rather stereotyped image, focusing on folkloristic characteristics based on the Mediterranean sense of honour, family, religion and blood. Obviously, these aspects are not completely fictional and are possibly the ones which attract most of the foreign attention and curiosity about the mafias. However, the reality is much more complex than a few uneducated mafiosi gathering around a laden table to discuss murders and control of the underworld. The mafias are an important component of the informal power structure of Italy and as such they have a historically deep connection with the economy and the political system.

The academic community has struggled against stereotyped images of the mafias since their appearance after WWII, when several US commissions described to the American public the image of a nation-wide conspiracy of Italian-American mafiosi conspiring against the United States. Scholars argued that this perception was misguided and based on prejudice rather than on empirical evidence. Studies suggested that the mafias should be better interpreted as a network of patron-client relationships, or social systems based on shared social, cultural and ethnic connections, or enterprises providing illicit products and services. Although today the alien conspiracy interpretation is discredited among academics, it is still popular in the perception of the general public.

The reasons are multiple. Clearly, the popular view of mafias profits the entertainment industry. Further, it is frequently exploited by practitioners and policymakers to rally the public on their side against a monstrous enemy. Frequently, academics face a challenging trade-off: either they support the view of an evil threat to civil society (more or less reluctantly adopting the same stereotyped approach based on scarce empirical evidence) or they advocate empirically-sound research, which inevitably uncovers a complexity of mechanisms placing scholars out of the reach of the media circuit and of the general public. This contrast of interests on the mafias (media, practitioners, policymakers and academics) generates a disharmonic situation. A common preference towards independent, empirical studies can hardly emerge. On top of this, the connections between mafias, economy and politics make it difficult to conduct research in the area. It is extremely easy to encounter powerful opposition. These elements make mafias a complex research topic, but at the same time it is crucial for understanding the Italian system on a national scale.

Indeed, contrary to the popular perception, the Italian mafias (i.e. hundreds of criminal organisations mostly belonging to three historical types: Cosa Nostra, the archetypal Sicilian mafia; the Camorra from Campania; and the ‘Ndrangheta from Calabria, although other minor types exist) have a nation-wide presence. In a study, I have tried to measure their presence in the Italian provinces from 1983 to 2010, creating the Mafia Index: a composite index which includes murders, criminal association offences, confiscated assets and city councils disbanded due to mafia infiltration. As Figure 1 shows, the highest presence is in the original areas of origin of the mafias: Western Sicily, Naples and Northern Campania and Southern Calabria. However, Northern provinces also show an important mafia presence, particularly in the North-Western industrial cities (e.g. Turin and Milan).

Figure 1: Mafia Index

Despite countless scandals and judicial cases, the involvement of the mafias in politics, remains largely under researched. A number of political scandals uncovered the political connections of the mafias. Nevertheless, the trials have not always resulted in convictions, owing to legal and political difficulties. Among the most famous cases, Giulio Andreotti (who served seven times as Italian Prime Minister) was tried for mafia association and finally acquitted in 2004. However, for the facts until the spring of 1980 the acquittal was due to the expiration of the statute of limitations. In fact, the Courts acknowledged his previous connections with the Cosa Nostra. Furthermore, Salvatore Cuffaro, President of the Sicilian region from 2001 to 2008, in 2011 was convicted of abetting Cosa Nostra and sentenced to seven years of imprisonment. Besides these famous cases, a number of investigations have demonstrated the political connections of mafias. Local politics (e.g. regional, provincial and municipal administrations) has frequently been infiltrated by the mafias at any latitude, as confirmed by recent news. On 9 October 2012, the Government, for the first time in history, has disbanded the city council of a regional capital city, Reggio Calabria (more than 180,000 inhabitants). There was strong evidence of the infiltration of the ‘Ndrangheta in the city administration. Two days later, a regional councillor of Lombardy was arrested for having bought approximately 11,000 votes from the ‘Ndrangheta at the price of €200,000 for the 2010 regional elections.

Despite countless scandals and judicial cases, the involvement of the mafias in politics, remains largely under researched. A number of political scandals uncovered the political connections of the mafias. Nevertheless, the trials have not always resulted in convictions, owing to legal and political difficulties. Among the most famous cases, Giulio Andreotti (who served seven times as Italian Prime Minister) was tried for mafia association and finally acquitted in 2004. However, for the facts until the spring of 1980 the acquittal was due to the expiration of the statute of limitations. In fact, the Courts acknowledged his previous connections with the Cosa Nostra. Furthermore, Salvatore Cuffaro, President of the Sicilian region from 2001 to 2008, in 2011 was convicted of abetting Cosa Nostra and sentenced to seven years of imprisonment. Besides these famous cases, a number of investigations have demonstrated the political connections of mafias. Local politics (e.g. regional, provincial and municipal administrations) has frequently been infiltrated by the mafias at any latitude, as confirmed by recent news. On 9 October 2012, the Government, for the first time in history, has disbanded the city council of a regional capital city, Reggio Calabria (more than 180,000 inhabitants). There was strong evidence of the infiltration of the ‘Ndrangheta in the city administration. Two days later, a regional councillor of Lombardy was arrested for having bought approximately 11,000 votes from the ‘Ndrangheta at the price of €200,000 for the 2010 regional elections.

The infiltration in Italian politics is surely due to the nature of the mafias. However, it is also favoured by the weakness of state institutions, as demonstrated by the international measures of corruption (e.g. Transparency International’s and World Bank’s Indexes). In this perspective, strengthening the rule of law and improving the quality of Italian governance may not only support economic growth (one of the current priorities particularly in Europe) but also prevent mafia infiltration.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/EMafia

_________________________________

Francesco Calderoni – Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore of Milan

Francesco Calderoni – Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore of Milan

Francesco Calderoni is assistant professor at the Faculty of Sociology at Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore of Milan. He was a Council of Europe expert for the reform of the Criminal Procedure Code of Georgia (2006) and Ukraine (2007) and an expert of the German Foundation for International Legal Cooperation for the reform of the Criminal Procedure Code of Romania (2007). He has been a researcher at Transcrime since September 2005. His areas of interest are organized crime, organized crime legislation, reforms of criminal procedure, crime proofing and social network analysis.